1938 New England hurricane

The 1938 New England Hurricane (also referred to as the Great New England Hurricane and the Long Island Express Hurricane)[1][2] was one of the deadliest and most destructive tropical cyclones to strike the United States. The storm formed near the coast of Africa on September 9, becoming a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale, before making landfall as a Category 3 hurricane[3] on Long Island on Wednesday, September 21. It is estimated that the hurricane killed 682 people,[4] damaged or destroyed more than 57,000 homes, and caused property losses estimated at $306 million ($4.7 billion in 2024).[5][6] Multiple other sources, however, mention that the 1938 hurricane might have really been a more powerful Category 4, having winds similar to Hurricanes Hugo, Harvey, Frederic and Gracie when it ran through Long Island and New England.[7][8] Also, numerous others estimate the real damage between $347 million and almost $410 million.[9] Damaged trees and buildings were still seen in the affected areas as late as 1951.[10] It remains the most powerful and deadliest hurricane in recorded New England history, perhaps eclipsed in landfall intensity only by the Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635.[11]

"Long Island Express" redirects here. For the auxiliary Interstate Highway signed I-495, see Long Island Expressway.Meteorological history

September 9, 1938

September 22, 1938

September 23, 1938

160 mph (260 km/h)

682 to 800 direct

$306 million (1938 USD)

Southeastern United States, Northeastern United States (particularly Connecticut, New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts), southwestern Quebec

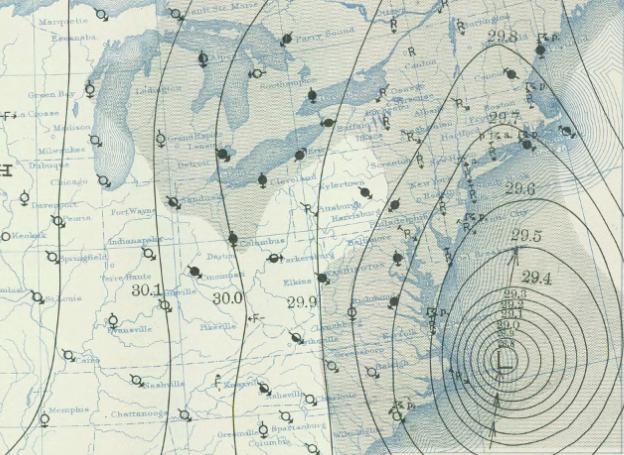

At the time, roughly half of the 1938 New England hurricane's existence went unnoticed. The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in 2012 concluded that the storm developed into a tropical depression on September 9 off the coast of West Africa, but the United States Weather Bureau was unaware that a tropical cyclone existed until September 16; by then, it was already a well-developed hurricane and had tracked westward toward the Sargasso Sea. It reached hurricane strength on September 15 and continued to strengthen to a peak intensity of 160 mph (260 km/h) near The Bahamas four days later, making it a Category 5-equivalent hurricane.[note 1] The storm was propelled northward, rapidly paralleling the East Coast before making landfalls on Long Island and Connecticut as a Category 3-equivalent hurricane on September 21. After moving inland, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and dissipated over Ontario on September 23.

Forecasting the storm[edit]

In 1938, United States forecasting lagged behind forecasting in Europe, where new techniques were being used to analyze air masses, taking into account the influence of fronts. A confidential report was released by the United States Forest Service, the parent agency of the United States Weather Bureau. It described the weather bureau's forecasting as "a sorry state of affairs" where forecasters had poor training and systematic planning was not used, and where forecasters had to "scrape by" to get information wherever they could. The Jacksonville, Florida, office of the weather bureau issued a warning on September 19 that a hurricane might hit Florida. Residents and authorities made extensive preparations, as they had endured the Labor Day Hurricane three years earlier. When the storm turned north, the office issued warnings for the Carolina coast and transferred authority to the bureau's headquarters in Washington.

At 9:00 am EDT on September 21, the Washington office issued northeast storm warnings north of Atlantic City and south of Block Island, Rhode Island, and southeast storm warnings from Block Island to Eastport, Maine.[24] The advisory, however, underestimated the storm's intensity and said that it was farther south than it actually was.[24] The office had yet to forward any information about the hurricane to the New York City office.[24] At 10:00 am EDT, the bureau downgraded the hurricane to a tropical storm. The 11:30 am advisory mentioned gale-force winds but nothing about a tropical storm or hurricane.[24]

That day, 28 year-old rookie Charles Pierce was standing in for two veteran meteorologists. He concluded that the storm would be squeezed between a high-pressure area located to the west and a high-pressure area to the east, and that it would be forced to ride up a trough of low pressure into New England. A noon meeting was called and Pierce presented his conclusion, but he was overruled by "celebrated" chief forecaster Charles Mitchell and his senior staff. In Boston, meteorologist E.B. Rideout told his WEEI radio listeners – to the skepticism of his peers – that the hurricane would hit New England.[25] At 2:00 pm, hurricane-force gusts were occurring on Long Island's South Shore and near hurricane-force gusts on the coast of Connecticut. The Washington office issued an advisory saying that the storm was 75 mi (120 km) east-southeast of Atlantic City and would pass over Long Island and Connecticut. Re-analysis of the storm suggests that the hurricane was farther north and just 50 mi (80 km) from Fire Island, and that it was stronger and larger than the advisory stated.[24]