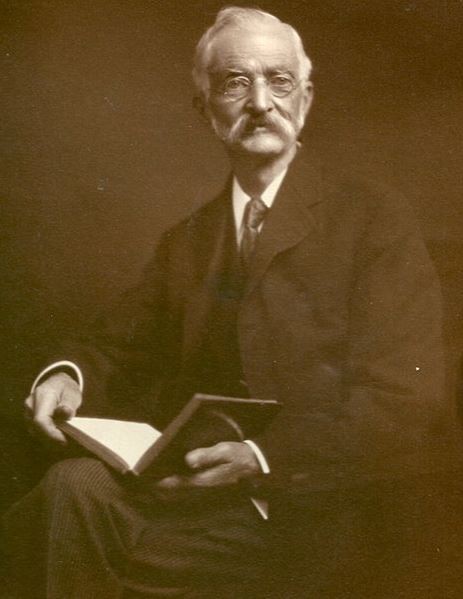

Algernon Thomas

Sir Algernon Phillips Withiel Thomas KCMG (3 June 1857 – 28 December 1937) was a New Zealand university professor, geologist, biologist and educationalist. He was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, England in 1857 and died in Auckland, New Zealand in 1937. He is best known for his early research (1880–83) into the life cycle of the sheep liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica), a discovery he shared with the German zoologist Rudolf Leuckart, his report on the eruption of Tarawera (1888) and his contribution to the development of New Zealand pedagogy.[1]

Background and education[edit]

Thomas was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, on 3 June 1857, the sixth child and second son of Edith Withiell Phillips (1826–1909) and her husband John Withiell Thomas (1823–1909), an accountant and, later, senior partner in the Manchester practice Thomas, Wade, Guthrie & Co.[2] Both his parents came from Redruth in Cornwall. His elder brother Ernest Chester Thomas, (1850–1892),[3] a Gray's Inn barrister by profession, obtained early recognition as Librarian of the Oxford Union (1874) and, subsequently, for his work as secretary of the Library Association of the United Kingdom (1878–1890) and for his 1888 edition of The philobiblon of Richard de Bury. Two of his elder sisters, Clara Irene Thomas (1852–1919) and Lilias Landon Thomas (1854–1929), actively promoted secondary education for women, notably as foundation headmistresses respectively of Sydenham High School (1887) and Edgbaston Church of England College for Girls (1886).

In 1861, Thomas' family moved to Manchester where he was educated privately before being sent as a boarder to Ockbrook School in Derby. He subsequently followed his brother to Manchester Grammar School. Inclined to scientific studies from an early age, Thomas profited from his attendance at Manchester Grammar during the regime of its reforming high master, Frederick Walker who had a reputation for ensuring that his pupils achieved the highest academic distinctions. Awarded a Brackenbury Natural Science Scholarship by Balliol College, he matriculated at Oxford on 20 October 1874, aged 17. Studying under Robert Clifton (physics), Henry Smith (mathematics), Joseph Prestwich (geology), Walter Fisher (chemistry), Henry Acland (human anatomy) and George Rolleston (biology), he obtained a second in mathematical honour moderations in 1876 and a first in natural sciences in the honour finals in 1877, taking his BA in 1878. In 1879 he was awarded a Burdett-Coutts scholarship in geology, undertaking post-graduate study in Italy (Stazione Zoologica, Naples), France, Switzerland and Germany (Philipps-Universität Marburg). He took his MA in 1881.

In late 1879, Rolleston, the Linacre professor of anatomy and physiology, appointed Thomas junior demonstrator in human and comparative anatomy at the University Museum, Oxford, in succession to Edward Bagnall Poulton. His responsibilities included practical teaching of microscopic preparations, dissecting and practical classes in embryology as well as lecturing; his pupils included Frank Beddard (1858–1925) and Halford Mackinder (1861–1947). Under Rolleston's somewhat erratic supervision – his health was failing – Thomas was commissioned by the Royal Agricultural Society to investigate the sheep liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica), a parasite flatworm that in the winter of 1879–80 had caused the loss of some three million sheep in England. Thomas' preliminary results, which, critically, established the basic life cycle of the parasite, were published in 1881 and 1882, with his analysis and conclusions appearing in 1883.[4] He was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society of London in 1882.

Emigration to New Zealand[edit]

Notwithstanding his father's relative wealth, his academic success and the overt support of Acland and the master of Balliol, Benjamin Jowett, Thomas was unclear as to where he might gain more remunerative employment subsequent to his appointment to the museum. In October 1882, following a number of disappointments, he applied successfully for the professorship of natural science at the soon-to-be-formed Auckland University College (AUC), a constituent college of the University of New Zealand. Selected on the recommendations of Thomas Huxley and Archibald Geikie, he delivered his first professorial lecture, 'a special discourse "On the Liver-parasite in Sheep"' alongside Acland at the University of Oxford in February 1883.[5] Thomas, accompanied by his younger sister Lucie Vernon Thomas (1862-1932), departed from London on 8 March 1883 on the SS Orient. Transferring to the SS Rotomahana in Melbourne, they arrived in Auckland on 1 May 1883 to find that, contrary to what Thomas had been led to believe at his interview, facilities were somewhat less than rudimentary.[6] Until 1885 when Parliament passed the Auckland University College Reserves Act, AUC was the only university college in New Zealand without either an endowment or a dedicated campus.[7] As well as having to establish a new department encompassing geology, botany and zoology in - to quote Beatrice Webb - 'quaint ramshackle wooden buildings', Thomas was also required to teach mathematics following the drowning of George Walker, the professor of mathematics.[8][9] Not only was Auckland the physical and intellectual antithesis of Oxford but there was also considerable antagonism to the very existence of the college among Auckland's dominant commercial class with the Auckland Chamber of Commerce calling for its funding to be diverted to more profitable purposes on the grounds that 'a University is for the few and that consequently its usefulness is circumscribed.'[10]

Aside from having to lecture and research, the scientific professorial staff were also required to locate suitable premises, assemble books, specimen, apparatus and teaching materials, establish laboratories, undertake fieldwork and, notwithstanding the absence of any support staff, administer their departments. Thomas was also elected chair of the Professorial Board and in that capacity delivered the inaugural address at the opening of AUC on 21 May 1883.[11] In addition, there was an expectation that they would also examine secondary students, give public lectures, provide reports on scientific matters to various branches of government and be active participants in the city's intellectual life. Thomas joined the Auckland Institute and Museum in June 1883, and was elected to its council in 1884 and its presidency in 1886, a position he held again in 1895 and between 1903 and 1905. In his first year of membership he delivered two lectures at the Institute: 'Remarks on specimens from the Naples Zoological Station' and 'Remarks on Mr Caldwell's researches on the development of the lower mammals of Australia' and for the next decade he continued to deliver up to three lectures a year. Subsequently, he was appointed chairman of the Trustees of the Museum and, in that position, played a significant role both in establishing the museum's scientific reputation and in ensuring it was suitably housed and maintained.

In the summer vacation following his arrival, between January and March 1884, Thomas travelled throughout New Zealand meeting colleagues at the other two university establishments, notably Thomas Jeffery Parker (1850–1897), professor of biology and curator of the University Museum at the University of Otago and Frederick Hutton (1836–1905), professor of biology at Canterbury University College. The visit both enabled him to assess the status of science in the country and provided him with the empirical basis on which he developed a teaching programme best suited to the needs of his students. It also opened up an informal network of local scientific researchers; he became particularly close to Parker with whom he initiated a research project focussing on the embryology of the Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus).[12]

While Thomas had good relations with his peers, his connection with the New Zealand scientific establishment, as embodied by James Hector, director of both the Colonial Museum and the New Zealand Geological Survey, manager of the New Zealand Institute and editor of its Transactions, was less congenial. Hector seems to have avoided meeting Thomas during his first visit to Wellington, leaving Thomas to observe merely that the Colonial Museum was 'old-fashioned' in appearance.[13] The influential Hector, a medical doctor by training, distrusted university-trained natural scientists recently arrived from the metropolis, such as Thomas and Parker. It was a view shared by James McKerrow, the surveyor general and a protégé of Hector's, who observed of Thomas and his colleague Frederick Douglas Brown, the professor of chemistry at AUC, that 'They are I fancy like some other learned men I have seen from Home, who have to unlearn a good deal after they come to the colony, and get quit of a deal of self-complacency. A very common notion of new arrivals, is, that Colonials are a sort of unkempt inferior race which it is the privilege and duty of them – the learned men – to make stepping stones of.'[14] For their part, Parker, Thomas and Brown were not so much keen to step on 'colonials', but rather unimpressed by the descriptive, unanalytical, nature of the prevailing scientific methodology and sceptical of the rigour of its practitioners, many of them self-trained. Hector's animus against the academic scientists is suggested by his failure to publish many of the papers submitted to him in his capacity as editor of the Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute.[15]

These tensions coalesced in June 1886 when the largest volcanic event in modern New Zealand history occurred at Mount Tarawera, 24 kilometres south east of Rotorua in the North Island. Following the eruption, the government commissioned Hector to provide a scientific report on the occurrence and its consequences. Undertaking a fleeting visit around the site he produced a report arguing that the eruption was, essentially, non-volcanic and of little scientific interest. As R F Keam remarks, 'No geologist today would accept Hector's model of the occurrence' and, even then, the deficiencies of the Hector report aroused criticism. In an effort to defuse the matter William Lanarch, the minister of mines, commissioned Hutton, Thomas and Brown to further report on the eruption. While Hutton evinced a degree of impatience in promulgating his opinion, Thomas was more circumspect and thorough in his fieldwork and his report, published two years later and separately from that of Hutton, was, in Keam's opinion, 'the polished product of meticulous research'; he further notes that 'Thomas would have been glad that he had distanced himself from Hutton's ideas on the matter'.[16]

Educational developments[edit]

From the time of his arrival in Auckland, Thomas evinced a particular interest in educational issues outside of his college responsibilities. He was keenly interested in technical education matters, notably agricultural science. In 1888 he addressed these issue in a series of provocative lectures and articles published in newspapers throughout the country in which he argued that given its dependence on mining and agriculture, New Zealand could only benefit from the proper teaching of agricultural botany and chemistry at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. His articles in the New Zealand Herald suggest both an awareness of the work of Arthur Acland's educational reform lobby group, the National Association for the Promotion of Technical and Secondary Education and a recognition that this work had significant relevance to New Zealand. The association was an Oxford creation – Acland himself was an honorary fellow of Balliol College – and many of those involved with it had served as lecturers with the university extension programme at Toynbee Hall in London's East End. In a statement that retains contemporary significance, Thomas opined that 'The true way ... to protect the interests of the working classes is to afford them opportunities of acquiring such knowledge and skill as will enable them to hold their own in competition with the rest of the world.'[30]

Perhaps surprisingly given its conservative ideology, the Herald editorialised its support for Thomas' progressive proposals, observing that 'Professor Thomas is distinctly of the present and of the future, as indeed his colleagues are, and it is on the fact that our professors have thoroughly caught the temper of the times, and have brought themselves in touch with the onward spirit of colonial life, that the best hopes are based that our University institutions will prove to be the most influential and valuable of our educational agencies.'[31] He also initiated a series of lectures on agricultural science at the AUC specifically aimed at teachers and farmers. For some years after, in the absence of any official activity, he provided advice and delivered lectures on agricultural matters to a wide range of agricultural organisations throughout the country.[32] Thomas, along with Brown, was also behind an ultimately successful move to establish a school of mines at AUC in 1906. By 1910 the AUC school had morphed into what Sinclair describes as 'a covert School of Engineering', a move that despite opposition from the University of New Zealand became official in 1923.[33]

Thomas's educational concerns prompted his election by the Senate of the University of New Zealand to the Auckland Grammar School Board in 1899, chaired by George Maurice O'Rourke who was also chairman of the AUC council. He was immediately elected vice-chairman and, in 1916, chairman in which position he served until his death in 1937[34] making him the second longest-serving chairman in Auckland Grammar’s history. Thomas' chairmanship of the board coincided with the last six years of James Tibbs' long period as headmaster of Auckland Grammar School. The younger Thomas had been a contemporary of Tibbs at Oxford and, given that both took mathematics honours, they were probably acquainted. But where Tibbs chafed under the provisions of the 1914 Education Act, Thomas seems to have relished the opportunity it provided to develop the Grammar Schools as intellectual powerhouses. Under Thomas' dominant influence the Board expanded the number of schools under its control from one, housed on an inadequate inner-city site, to five, all housed in new, well-equipped premises: Auckland Girls' Grammar School (1909); Auckland Grammar School (1915); Epsom Girls' Grammar School (1917); Mt Albert Grammar School (1922); and Takapuna Grammar School (1927). In contrast to his successors as chair of the Auckland Grammar School Board, Thomas played a highly visible role in the activities of the schools until his death. He was a vice-chairman of the Dilworth Trust Board, the body responsible for Dilworth School, between 1906 and 1937 and a member of the Auckland Teachers' Training College Committee of Advice between 1906 and 1914.

Thomas was a member of the Senate of the University of New Zealand between 1899 and 1903 and, again, between 1921 and 1933. He was also a member of the AUC council between 1919 and 1925. He was the Bishop of Waiapu's nominated member of the St John's Theological College Board of Governors between 1910 and 1911.

Public science[edit]

In October 1913, a newly elected Reform government introduced legislation into the New Zealand Parliament creating a governmental scientific advisory body, the Board of Science and Art.[35] Ross Galbreath asserts that the government intended that the board's primary function was to manage the Dominion (formerly Colonial) Museum and to publish scientific journals and reports, but its members appear to have had greater ambitions.[36] Along with six others, Thomas was appointed to the board by an Order in Council in 1915. He appears to have played a significant role in galvanising its activities, notably in calling for 'a central advisory board' for science and industry.[37] But early moves to establish a scientific advisory body modelled on the British Department of Scientific and Industrial Research failed due to the absence of any significant political support. It was only with the visit in 1926 of Frank Heath, permanent secretary of the British DSIR, along with a decision by the British Empire Marketing Board to fund agricultural research in New Zealand, that a body to advise on the promotion of science in industry, also known as the DSIR, was formed.[38]

Personal life[edit]

Notwithstanding the suggestion of Francis Dillon Bell, the New Zealand Agent General in London 'that a Mrs Professor would be a very great addition to the colony', Thomas arrived in New Zealand a bachelor although there are indications he had an unsuccessful shipboard romance on the outward voyage. He was accompanied by his younger sister Lucie Vernon Thomas (1862–1932) who would act as his hostess and housekeeper until February 1885. Soon after his arrival, he purchased a villa at Narrow Neck on Auckland's North Shore. On 19 November 1887 he married Emily Sarah Nolan Russell (1867–1950), the third of six daughters of Mary Ann Nolan (1834–1931) and her husband John Benjamin Russell (1834–1894), an Auckland solicitor.

The Russells were a well-connected Auckland family: J B Russell's practice, Russell & Campbell, was – and, as Russell McVeagh, remains – one of Auckland's leading legal firms; his eldest brother was the lawyer, politician and financier Thomas Russell. Emily Thomas was a well-educated, travelled, woman of progressive ideas; in 1895 she was nominated unsuccessfully by the Auckland, Devonport and Ponsonby Schools Committees for a seat on the Auckland Education Board. Unfortunately in 1905 and, again, in 1908 she experienced a specific acute reactive disorder that led to her being admitted to Ashburn Hall, a private asylum in Dunedin. She remained there until March 1950 when she was transferred to Kingseat Hospital near Auckland, shortly before her death. Thomas, a lifelong cigarette smoker, died suddenly in Auckland on 28 December 1937. The Thomases had four children: three sons, Acland Withiel (1888–1962), Norman Russell Withiel (1891–1969), Arthur Edward Withiel (1904–1992); and a daughter, Mary Wynfrida Withiel (1893–1974).

Honours[edit]

Besides being a fellow of the Linnean Society of London (FLS, 1882), Thomas was a fellow of the Geological Society (FGS, 1888), a fellow of the New Zealand Institute (1905), and after its transmogrification from an Institute into a royal society, an original fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand, (FRSNZ, 1919) and an honorary fellow of the New Zealand Institute of Horticulture (1936). Following his resignation from the chair of biology and geology at Auckland University College in 1913 he was made professor emeritus by the college senate. He was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal in 1935.[39] In the 1937 George VI Coronation Honours Thomas was made Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) for services to education, a then extraordinary distinction for a New Zealander.[40] Pallbearers at his funeral included the Hon Peter Fraser, minister of education and later prime minister in the first Labour administration.[41]

The Austrian naturalist and explorer Andreas Reischek named New Zealand's westernmost lake in Fiordland (45°59'14.3"S 166°30'09.8"E) after Thomas in 1887.[42] Following his death, the executors of his estate gifted 100 acres (42 hectares) of land at Piha to the Auckland City Council; this was supplemented in 1963 by the gift of Lion Rock (Te Piha), an eroded 16-million-year-old volcanic neck, that was acquired by two of his sons, Acland and Norman, from Te Kawerau in 1941.[43] These gifts were commemorated in 2008 with the naming of a part of the gift as the Sir Algernon Thomas Green. In 1968, largely on the initiative of Sir Douglas Robb, chancellor of the University of Auckland, the university's new biological sciences building was named in his honour. Following the subdivision of his garden, a road formed through the property (primarily through what had been his 'cow paddock') was named Withiel Drive in his memory, as was a 0.7-hectare (1.7-acre) reserve donated to the Auckland City Council in 1949 by his son Norman, which was based on a remnant of the Maungawhau lava field that he had preserved, Withiel Thomas Park.