Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States.[a] The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens, the Alien Enemies Act gave the president additional powers to detain non-citizens during times of war, and the Sedition Act criminalized false and malicious statements about the federal government. The Alien Friends Act and the Sedition Act expired after a set number of years, and the Naturalization Act was repealed in 1802. The Alien Enemies Act is still in effect.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were controversial. They were supported by the Federalist Party, and supporters argued that the bills strengthened national security during the Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war with France from 1798 to 1800. The acts were denounced by Democratic-Republicans as suppression of voters and violation of free speech under the First Amendment. While they were in effect, the Alien and Sedition Acts, and the Sedition Act in particular, were used to suppress publishers affiliated with the Democratic-Republicans, and several publishers were arrested for criticism of the Adams administration. The Democratic-Republicans took power in 1800, in part because of backlash to the Alien and Sedition Acts, and all but the Alien Enemies Act were eliminated by the next Congress. The Alien Enemies Act has been invoked several times since, particularly during World War II. The Alien and Sedition Acts are generally received negatively by modern historians, and the U.S. Supreme Court has since indicated that aspects of the laws would likely be found unconstitutional today.

Acts[edit]

Alien Friends Act[edit]

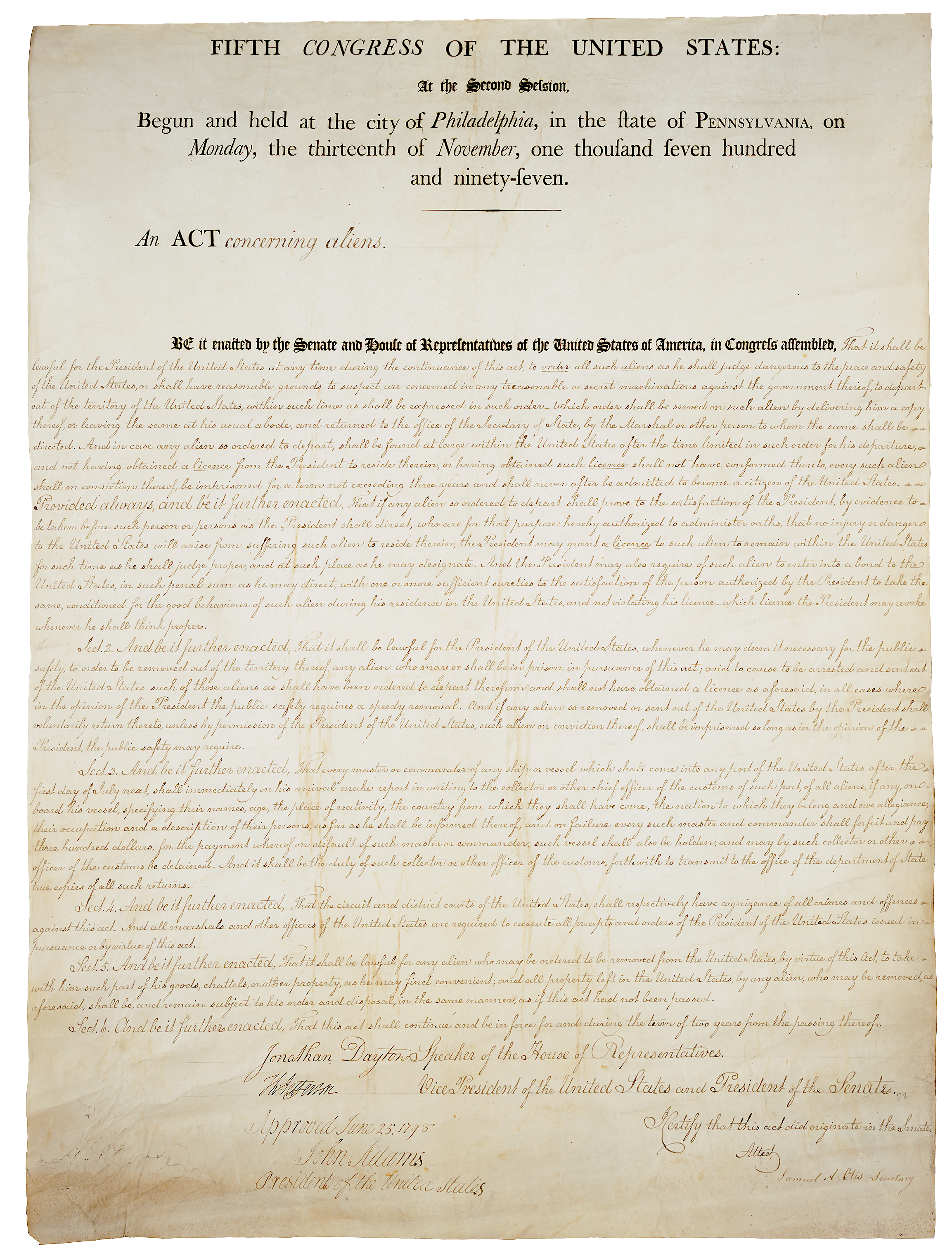

The Alien Friends Act (officially "An Act Concerning Aliens") authorized the president to arbitrarily deport any non-citizen that was determined to be "dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States."[1] Once a non-citizen was determined to be dangerous, or was suspected of conspiring against the government, the president had the power to set a reasonable amount of time for departure, and remaining after the time limit could result to up to three years in prison. The law was never directly enforced, but it was often used in conjunction with the Sedition Act to suppress criticism of the Adams administration. Upon enactment, the Alien Friends Act was authorized for two years, and it was allowed to expire at the end of this period. Democratic-Republicans opposed the law, with Thomas Jefferson referring to it as "a most detestable thing... worthy of the 8th or 9th century."[2]: 249

While the law was not directly enforced, it resulted in the voluntary departure of foreigners who feared that they would be charged under the act. The Adams administration encouraged these departures, and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering would ensure that the ships were granted passage. Though Adams did not delegate the final decision-making power, Secretary Pickering was responsible for overseeing enforcement of the Alien Friends Act. Both Adams and Pickering considered the law too weak to be effective; Pickering expressed his desire for the law to require sureties and authorize detainment prior to deportation.[3]

Many French nationals were considered for deportation, but were allowed to leave willingly, or Adams declined to take action against them. These figures included: philosopher Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney, General Victor Collot, scholar Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry, diplomat Victor Marie du Pont, journalist William Duane, scientist Joseph Priestley, and journalist William Cobbett. Secretary Pickering also proposed applying the act against the French diplomatic delegation to the United States, but Adams refused. Journalist John Daly Burk agreed to leave under the act informally to avoid being tried for sedition, but he went into hiding in Virginia until the act's expiration.[3]

Alien Enemies Act[edit]

The Alien Enemies Act (officially "An Act Respecting Alien Enemies") was passed to supplement the Alien Friends Act, granting the government additional powers to regulate non-citizens that would take effect in times of war.[3][4] Under this law, the president could authorize the arrest, relocation, or deportation of any male over the age of 14 who hailed from a foreign enemy country.[5] It also provided some legal protections for those subject to the law.[6] Unlike the other acts, this act was largely unopposed by the Democratic-Republicans.[2]: 249

The Alien Enemies Act was not allowed to expire with the other Alien and Sedition Acts, and it remains in effect as Chapter 3, Sections 21–24 of Title 50 of the United States Code.[7] President James Madison invoked the act against British nationals during the War of 1812.[8] President Woodrow Wilson invoked the act against nationals of the Central Powers during World War I. In 1918, an amendment to the act struck the provision restricting the law to males.[9]

On December 7, 1941, in response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the authority of the revised Alien Enemies Act to issue presidential proclamations #2525 (Alien Enemies – Japanese), #2526 (Alien Enemies – German), and #2527 (Alien Enemies – Italian), to apprehend, restrain, secure, and remove Japanese, German, and Italian non-citizens.[10] Roosevelt later cited further wartime powers to issue Executive Order 9066, which interned Japanese Americans using powers unrelated to the Alien Enemies Act.[11][12] Hostilities with Germany and Italy ended in May 1945, and President Harry S. Truman issued presidential proclamation #2655 on July 14. The proclamation gave the Attorney General authority regarding enemy aliens within the continental United States, to decide whether they are "dangerous to the public peace and safety of the United States," to order them removed, and to create regulations governing their removal, citing the Alien Enemies Act.[13] On September 8, 1945, Truman issued presidential proclamation #2662, which authorized the Secretary of State to remove enemy aliens that had been sent to the United States from Latin American countries.[14] On April 10, 1946, Truman issued presidential proclamation #2685, which modified the previous proclamation, and set a 30-day deadline for removal.[15]

In Ludecke v. Watkins (1948), the Supreme Court interpreted the time of release under the Alien Enemies Act.[16] German alien Kurt G. W. Ludecke was detained in 1941, under Proclamation 2526, and continued to be held after cessation of hostilities. In 1947, Ludecke petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus to order his release, after the Attorney General ordered him deported. The court ruled 5–4 to release Ludecke, but also found that the Alien Enemies Act allowed for detainment beyond the time hostilities ceased, until an actual treaty was signed with the hostile nation or government.[17]

Reaction[edit]

After the passage of the highly unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts, protests occurred across the country,[38] with some of the largest being seen in Kentucky, where the crowds were so large they filled the streets and the entire town square of Lexington.[39] Critics argued that they were primarily an attempt to suppress voters who disagreed with the Federalist party and its teachings, and violated the right of freedom of speech in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[40] They also raised concerns that the Alien and Sedition acts gave disproportionate power to the federal executive compared to state governments and other branches of the federal government.[23] Noting the outrage among the populace, the Democratic-Republicans made the Alien and Sedition Acts an important issue in the 1800 presidential election campaign. While government authorities prepared lists of aliens for deportation, many aliens fled the country during the debate over the Alien and Sedition Acts, and Adams never signed a deportation order.[24]: 187–193

The Virginia and Kentucky state legislatures also passed the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, secretly authored by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, denouncing the federal legislation.[41][42][43] While the eventual resolutions followed Madison in advocating "interposition", Jefferson's initial draft would have nullified the Acts and even threatened secession.[b] Jefferson's biographer Dumas Malone argued that this might have gotten Jefferson impeached for treason, had his actions become known at the time.[45] In writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood".[46]

The Alien and Sedition Acts were never appealed to the Supreme Court, whose power of judicial review was not established until Marbury v. Madison in 1803. Subsequent mentions in Supreme Court opinions beginning in the mid-20th century have assumed that the Sedition Act would today be found unconstitutional.[c] Most modern historians view the Alien and Sedition Acts in a negative light, considering them to have been a mistake.[22][48]