Allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis, of which the seasonal type is called hay fever, is a type of inflammation in the nose that occurs when the immune system overreacts to allergens in the air.[6] Signs and symptoms include a runny or stuffy nose, sneezing, red, itchy, and watery eyes, and swelling around the eyes.[1] The fluid from the nose is usually clear.[2] Symptom onset is often within minutes following allergen exposure, and can affect sleep and the ability to work or study.[2][8] Some people may develop symptoms only during specific times of the year, often as a result of pollen exposure.[3] Many people with allergic rhinitis also have asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, or atopic dermatitis.[2]

"Hay fever" redirects here. For other uses, see Hay fever (disambiguation).Allergic rhinitis

Hay fever, pollenosis

20 to 40 years old[2]

Genetic and environmental factors[3]

Based on symptoms, skin prick test, blood tests for specific antibodies[4]

Exposure to animals early in life[3]

Nasal steroids, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, cromolyn sodium, leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast, allergen immunotherapy[5][6]

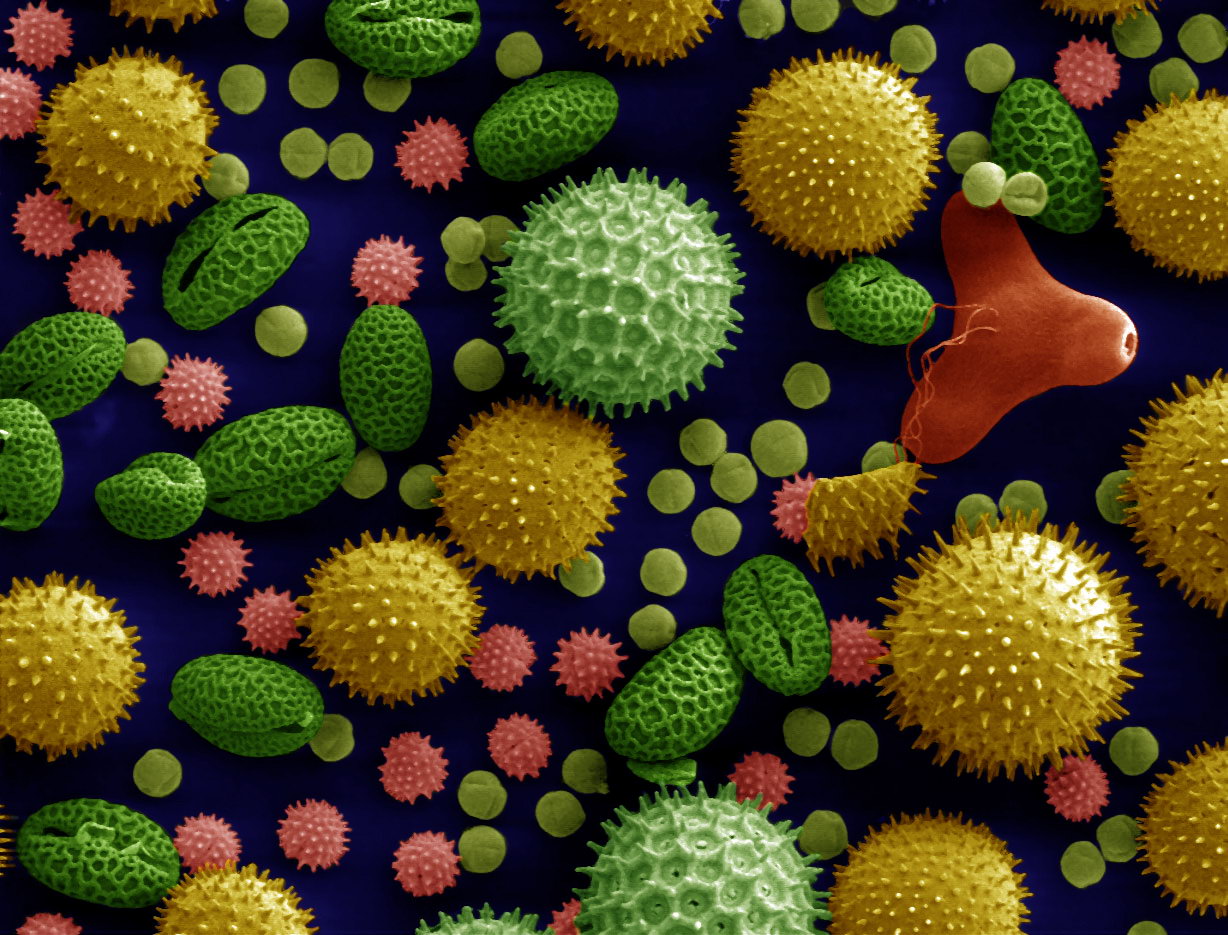

Allergic rhinitis is typically triggered by environmental allergens such as pollen, pet hair, dust, or mold.[3] Inherited genetics and environmental exposures contribute to the development of allergies.[3] Growing up on a farm and having multiple siblings decreases this risk.[2] The underlying mechanism involves IgE antibodies that attach to an allergen, and subsequently result in the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine from mast cells.[2] It causes mucous membranes in the nose, eyes and throat to become inflamed and itchy as they work to eject the allergen.[9] Diagnosis is typically based on a combination of symptoms and a skin prick test or blood tests for allergen-specific IgE antibodies.[4] These tests, however, can give false positives.[4] The symptoms of allergies resemble those of the common cold; however, they often last for more than two weeks and, despite the common name, typically do not include a fever.[3]

Exposure to animals early in life might reduce the risk of developing these specific allergies.[3] Several different types of medications reduce allergic symptoms, including nasal steroids, antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, cromolyn sodium, and leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast.[5] Oftentimes, medications do not completely control symptoms, and they may also have side effects.[2] Exposing people to larger and larger amounts of allergen, known as allergen immunotherapy (AIT), is often effective.[6] The allergen can be given as an injection under the skin or as a tablet under the tongue.[6] Treatment typically lasts three to five years, after which benefits may be prolonged.[6]

Allergic rhinitis is the type of allergy that affects the greatest number of people.[10] In Western countries, between 10 and 30% of people are affected in a given year.[2][7] It is most common between the ages of twenty and forty.[2] The first accurate description is from the 10th-century physician Abu Bakr al-Razi.[11] In 1859, Charles Blackley identified pollen as the cause.[12] In 1906, the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[10] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[13][14] Although the scent per se is irrelevant, the correlation with hay is accurate, as peak hay-harvesting season overlaps with peak pollen season, and hay-harvesting work puts people in close contact with seasonal allergens.

Prevention[edit]

Prevention often focuses on avoiding specific allergens that cause an individual's symptoms. These methods include not having pets, not having carpets or upholstered furniture in the home, and keeping the home dry.[43] Specific anti-allergy zippered covers on household items like pillows and mattresses have also proven to be effective in preventing dust mite allergies.[35]

Studies have shown that growing up on a farm and having many older siblings can decrease an individual's risk for developing allergic rhinitis.[2]

Studies in young children have shown that there is higher risk of allergic rhinitis in those who have early exposure to foods or formula or heavy exposure to cigarette smoking within the first year of life.[44][45]

History[edit]

The first accurate description is from the 10th century physician Rhazes.[11] Pollen was identified as the cause in 1859 by Charles Blackley.[12] In 1906 the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[10] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[13][14] Although the scent per se is irrelevant, the correlation with hay checks out, as peak hay-harvesting season overlaps with peak pollen season, and hay-harvesting work puts people in close contact with seasonal allergens.