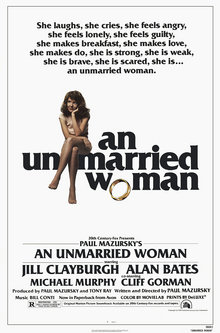

An Unmarried Woman

An Unmarried Woman is a 1978 American romantic comedy-drama film written and directed by Paul Mazursky and starring Jill Clayburgh, Alan Bates, Michael Murphy, and Cliff Gorman. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress (Clayburgh).

Plot[edit]

Erica Benton works part-time at a SoHo art gallery and is in a seemingly happy marriage to Martin, a successful businessman. They live together with their teenage daughter Patti in an upscale Upper East Side apartment. Martin, however, has been having a year-long affair with a much younger woman named Marcia. When he confesses to Erica that he loves his mistress and wants to marry her, Erica is devastated, and Martin moves out.

With the help of Patti, her circle of close friends, and a therapist, Erica slowly comes to terms with the divorce and begins to get her life back on track. She reluctantly tries dating again, but after Martin's betrayal and a disastrous blind date, she is even warier of ever finding a suitable man again. Her mistrust of men threatens her relationship with Patti, as she takes out her frustrations on Patti's boyfriend, Phil. Out of desperation, Erica has sex with Charlie, an obnoxious, chauvinistic co-worker, but she does not find the experience fulfilling.

As she grows more accustomed to her new life, she meets Saul, an abstract painter, and begins a relationship with him. Both value their independence and so have a difficult time adjusting to domestic life. When Patti meets Saul, she is initially hostile, believing Erica is trying to bring him in to replace Martin, which Saul assures Patti is not his intention.

After a few tense meetings, Martin and Erica begin to act cordially towards each other, only for Martin to reveal that Marcia has left him and he wants Erica back. Erica rebuffs him.

Saul tries to convince Erica to come with him to his home in Vermont for the summer, where he spends five months every year with his children, but she declines, not wishing to leave her daughter and her life behind for so long. Outside Saul's building, Erica helps him lower one of his paintings from his loft to the sidewalk. Shortly before driving away in his car, Saul reveals that the painting is a gift for Erica, leaving her to carry the giant canvas through the busy streets of Manhattan.

Production[edit]

Paul Mazursky began writing the script in 1976 after interviewing several different women about their thoughts on marriage and independence. He initially offered the role of Erica to Jane Fonda, who passed to star in Julia. Mazursky also considered Barbra Streisand for the lead but did not hear back from her agent. Finally, Jill Clayburgh was considered without an audition after Mazursky saw her in a New York play. At 32 years old, Clayburgh was thought to be too young to play a wife in a 16-year marriage with a teenage daughter, but Clayburgh returned to Mazursky's office having styled herself in fashions indicative of an older woman and secured the part.

Principal photography began on April 5, 1977, in New York City, with the main locations being Manhattan's Upper East Side and SoHo neighborhoods.[4] Clayburgh worked the entire shoot without a day off; her character was written into every scene of a film that was on a tight budget.

Anthony Hopkins was offered the role of Saul but turned it down because the character does not show up until past the midway point of the script. British actor Alan Bates, whom Mazursky had always admired and who had never appeared in an American film, was given the part. Bates had some misgivings because he did not want to leave his dying father in England, but Mazursky assured him that he would be given seven days to be with his father in case of a tragic event. Bates conceded and his father died after he returned home.

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that "Clayburgh is nothing less than extraordinary in what is the performance of the year to date. In her we see intelligence battling feeling – reason backed against the wall by pushy needs."[5]

Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote: