Animal communication

Animal communication is the transfer of information from one or a group of animals (sender or senders) to one or more other animals (receiver or receivers) that affects the current or future behavior of the receivers.[1][2] Information may be sent intentionally, as in a courtship display, or unintentionally, as in the transfer of scent from predator to prey with kairomones. Information may be transferred to an "audience" of several receivers.[3] Animal communication is a rapidly growing area of study in disciplines including animal behavior, sociology, neurology and animal cognition. Many aspects of animal behavior, such as symbolic name use, emotional expression, learning and sexual behavior, are being understood in new ways.

When the information from the sender changes the behavior of a receiver, the information is referred to as a "signal". Signalling theory predicts that for a signal to be maintained in the population, both the sender and receiver should usually receive some benefit from the interaction. Signal production by senders and the perception and subsequent response of receivers are thought to coevolve.[4] Signals often involve multiple mechanisms, e.g. both visual and auditory, and for a signal to be understood the coordinated behaviour of both sender and receiver require careful study.

Animal languages[edit]

The sounds animals make are important because they communicate the animals' state.[5] Some animals species have been taught simple versions of human languages.[6] Animals can use, for example, electrolocation and echolocation to communicate about prey and location.[7]

Autocommunication[edit]

Autocommunication is a type of communication in which the sender and receiver are the same individual. The sender emits a signal that is altered by the environment and eventually is received by the same individual. The altered signal provides information that can indicate food, predators or conspecifics. Because the sender and receiver are the same animal, selection pressure maximizes signal efficacy, i.e. the degree to which an emitted signal is correctly identified by a receiver despite propagation distortion and noise. There are some species, such as the pacific herring, which have evolved to intercept these messages from their predators. They are able to use it as an early warning sign and respond defensively.[69] There are two types of autocommunication. The first is active electrolocation, where the organism emits an electrical pulse through its electric organ and senses the projected geometrical property of the object. This is found in the electric fish Gymnotiformes (knifefishes) and Mormyridae(elephantfish).[70] The second type of autocommunication is echolocation, found in bats and toothed whales. Echolocation involves emitting sounds and interpreting the vibrations that return from objects.[71] In bats, echolocation also serves the purpose of mapping their environment. They are capable of recognizing a space they have been in before without any visible light because they can memorize patterns in the feedback they get from echolocation.[72]

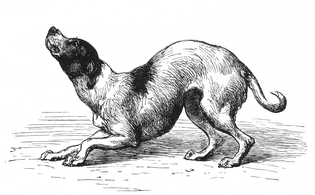

As described above, many animal gestures, postures, and sounds, convey meaning to nearby animals. These signals are often easier to describe than to interpret. It is tempting, especially with domesticated animals and apes, to anthropomorphize, that is, to interpret animal actions in human terms, but this can be quite misleading; for example, an ape's "smile" is often a sign of aggression. Also, the same gesture may have different meanings depending on context within which it occurs. For example, a domestic dog's tail wag and posture may be used in different ways to convey many meanings as illustrated in Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872. Some of Darwin's illustrations are reproduced here.

Errors in communication[edit]

There becomes possibility for error within communication between animals when certain circumstances apply.[101] These circumstances could include distance between the two communicating subjects, as well as the complexity of the signal that is being communicated to the "listener" of the situation. It may not always be clear to the "listener" where the location of the communication is coming from, as the "singer" can sometimes deceive them and create more error.[102]