Animism

Animism (from Latin: anima meaning 'breath, spirit, life')[1][2] is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence.[3][4][5][6] Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases words—as being animated, having agency and free will.[7] Animism is used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many Indigenous peoples[8] in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions.[9] Animism is a metaphysical belief which focuses on the supernatural universe (beyond logical foundations and procedures): specifically, on the concept of the immaterial soul.[10]

For other uses, see Animism (disambiguation).

Although each culture has its own mythologies and rituals, animism is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion").[11] The term "animism" is an anthropological construct.

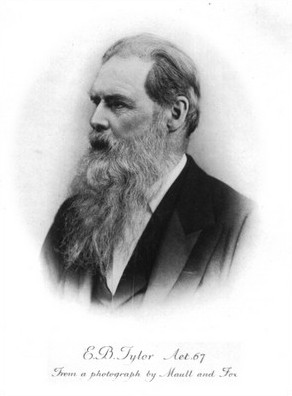

Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinions differ on whether animism refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Edward Tylor. It is "one of anthropology's earliest concepts, if not the first."[12]

Animism encompasses beliefs that all material phenomena have agency, that there exists no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical world, and that soul, spirit, or sentience exists not only in humans but also in other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features (such as mountains and rivers), and other entities of the natural environment. Examples include water sprites, vegetation deities, and tree spirits, among others. Animism may further attribute a life force to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists, such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan, and many contemporary Pagans.[13]

Etymology[edit]

English anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor initially wanted to describe the phenomenon as spiritualism, but he realized that it would cause confusion with the modern religion of spiritualism, which was then prevalent across Western nations.[14] He adopted the term animism from the writings of German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl,[15] who had developed the term animismus in 1708 as a biological theory that souls formed the vital principle, and that the normal phenomena of life and the abnormal phenomena of disease could be traced to spiritual causes.[16]

The origin of the word comes from the Latin word anima, which means life or soul.[17]

The first known usage in English appeared in 1819.[18]

Animist life[edit]

Non-human animals[edit]

Animism entails the belief that all living things have a soul, and thus, a central concern of animist thought surrounds how animals can be eaten, or otherwise used for humans' subsistence needs.[104] The actions of non-human animals are viewed as "intentional, planned and purposive",[105] and they are understood to be persons, as they are both alive, and communicate with others.[106]

In animist worldviews, non-human animals are understood to participate in kinship systems and ceremonies with humans, as well as having their own kinship systems and ceremonies.[107] Harvey cited an example of an animist understanding of animal behavior that occurred at a powwow held by the Conne River Mi'kmaq in 1996; an eagle flew over the proceedings, circling over the central drum group. The assembled participants called out kitpu ('eagle'), conveying welcome to the bird and expressing pleasure at its beauty, and they later articulated the view that the eagle's actions reflected its approval of the event, and the Mi'kmaq's return to traditional spiritual practices.[108]

In animism, rituals are performed to maintain relationships between humans and spirits. Indigenous peoples often perform these rituals to appease the spirits and request their assistance during activities such as hunting and healing. In the Arctic region, certain rituals are common before the hunt as a means to show respect for the spirits of animals.[109]

Flora[edit]

Some animists also view plant and fungi life as persons and interact with them accordingly.[110] The most common encounter between humans and these plant and fungi persons is with the former's collection of the latter for food, and for animists, this interaction typically has to be carried out respectfully.[111] Harvey cited the example of Māori communities in New Zealand, who often offer karakia invocations to sweet potatoes as they dig up the latter. While doing so, there is an awareness of a kinship relationship between the Māori and the sweet potatoes, with both understood as having arrived in Aotearoa together in the same canoes.[111]

In other instances, animists believe that interaction with plant and fungi persons can result in the communication of things unknown or even otherwise unknowable.[110] Among some modern Pagans, for instance, relationships are cultivated with specific trees, who are understood to bestow knowledge or physical gifts, such as flowers, sap, or wood that can be used as firewood or to fashion into a wand; in return, these Pagans give offerings to the tree itself, which can come in the form of libations of mead or ale, a drop of blood from a finger, or a strand of wool.[112]

The elements[edit]

Various animistic cultures also comprehend stones as persons.[113] Discussing ethnographic work conducted among the Ojibwe, Harvey noted that their society generally conceived of stones as being inanimate, but with two notable exceptions: the stones of the Bell Rocks and those stones which are situated beneath trees struck by lightning, which were understood to have become Thunderers themselves.[114] The Ojibwe conceived of weather as being capable of having personhood, with storms being conceived of as persons known as 'Thunderers' whose sounds conveyed communications and who engaged in seasonal conflict over the lakes and forests, throwing lightning at lake monsters.[114] Wind, similarly, can be conceived as a person in animistic thought.[115]

The importance of place is also a recurring element of animism, with some places being understood to be persons in their own right.[116]

Other usage[edit]

Science[edit]

In the early 20th century, William McDougall defended a form of animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911).

Physicist Nick Herbert has argued for "quantum animism" in which the mind permeates the world at every level: