Around the World in Eighty Days

Around the World in Eighty Days (French: Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours) is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate the world in 80 days on a wager of £20,000 (equivalent to £1.9 million in 2019) set by his friends at the Reform Club. It is one of Verne's most acclaimed works.[4]

This article is about the 1872 novel written by Jules Verne. For other uses, see Around the World in Eighty Days (disambiguation).Author

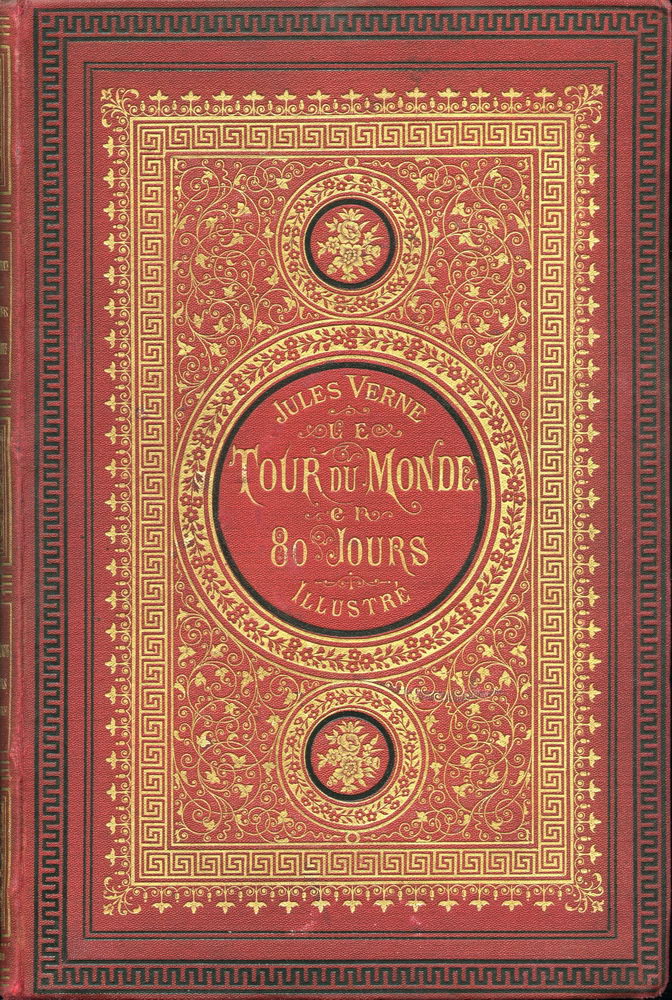

Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours

French

Le Temps (as serial)[2]

Pierre-Jules Hetzel (book form)

France

1873

Background and analysis[edit]

Around the World in Eighty Days was written during difficult times, both for France and Verne. It was during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) in which Verne was conscripted as a coastguard; he was having financial difficulties (his previous works were not paid royalties); his father had died recently; and he had witnessed a public execution, which had disturbed him.[6]

The technological innovations of the 19th century had opened the possibility of rapid circumnavigation, and the prospect fascinated Verne and his readership. In particular, three technological breakthroughs occurred in 1869–1870 that made a tourist-like around-the-world journey possible for the first time: the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in America (1869), the opening of the Suez Canal (1869), and the linking of the Indian railways across the sub-continent (1870). It was another notable mark at the end of an age of exploration and the start of an age of fully global tourism that could be enjoyed in relative comfort and safety. It sparked the imagination that anyone could sit down, draw up a schedule, buy tickets and travel around the world, a feat previously reserved for only the most heroic and hardy of adventurers.[6]

The story began serialization in Le Temps on 6 November 1872.[7] The story was published in installments over the next 45 days, with its ending timed to synchronize Fogg's December 21 deadline with the real world. Chapter XXXV appeared on 20 December;[8] 21 December, the date upon which Fogg was due to appear back in London, did not include an installment of the story;[9] on 22 December, the final two chapters announced Fogg's success.[10] As it was being published serially for the first time, some readers believed that the journey was actually taking place – bets were placed, and some railway companies and ship liner companies lobbied Verne to appear in the book. It is unknown if Verne submitted to their requests, but the descriptions of some rail and shipping lines leave some suspicion he was influenced.[6]

Concerning the final coup de théâtre, Fogg had thought it was one day later than it actually was because he had forgotten that during his journey, he had added a full day to his clock, at the rate of an hour per 15° of longitude crossed. At the time of publication and until 1884, a de jure International Date Line did not exist. If it did, he would have been made aware of the change in date once he reached this line. Thus, the day he added to his clock throughout his journey would be removed upon crossing this imaginary line. However, Fogg's mistake would not have been likely to occur in the real world because a de facto date line did exist. The UK, India, and the US had the same calendar with different local times. When he arrived in San Francisco, he would have noticed that the local date was one day earlier than shown in his travel diary. Consequently, it is unlikely he would fail to notice that the departure dates of the transcontinental train in San Francisco and of the China steamer in New York were one day earlier than his travel diary. He would also somehow have to avoid looking at any newspapers. Additionally, in Who Betrays Elizabeth Bennet?, John Sutherland points out that Fogg and company would have to be "deaf, dumb and blind" not to notice how busy the streets were on an apparent "Sunday", with the Sunday Observance Act 1780 still in effect.[11]

Following publication in 1873, various people attempted to follow Fogg's fictional circumnavigation, often within self-imposed constraints: