Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn (Scottish Gaelic: Blàr Allt nam Bànag or Blàr Allt a' Bhonnaich) was fought on 23–24 June 1314, between the army of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, and the army of King Edward II of England, during the First War of Scottish Independence. It was a decisive victory for Robert Bruce and formed a major turning point in the war, which ended 14 years later with the de jure restoration of Scottish independence under the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton. For this reason, the Battle of Bannockburn is widely considered a landmark moment in Scottish history.[10]

Battle of Bannockburn

21 March 2011

King Edward II invaded Scotland after Bruce demanded in 1313 that all supporters, still loyal to ousted Scottish king John Balliol, acknowledge Bruce as their king or lose their lands. Stirling Castle, a Scots royal fortress occupied by the English, was under siege by the Scottish army. King Edward assembled a formidable force of soldiers to relieve it—the largest army ever to invade Scotland. The English summoned 25,000 infantry soldiers and 2,000 horses from England, Ireland and Wales against 6,000 Scottish soldiers, that Bruce had divided into three different contingents.[10] Edward's attempt to raise the siege failed when he found his path blocked by a smaller army commanded by Bruce.[10]

The Scottish army was divided into four divisions of schiltrons commanded by (1) Bruce, (2) his brother Edward Bruce, (3) his nephew, Thomas Randolph, the Earl of Moray and (4) one jointly commanded by Sir James Douglas and the young Walter the Steward.[11] Bruce's friend, Angus Og Macdonald, Lord of the Isles, brought thousands of Islesmen to Bannockburn, including galloglass warriors, and King Robert assigned them the place of honour at his side in his own schiltron with the men of Carrick and Argyll.[12]

After Robert Bruce killed Sir Henry de Bohun on the first day of the battle, the English withdrew for the day. That night, Sir Alexander Seton, a Scottish noble serving in Edward's army, defected to the Scottish side and informed King Robert of the English camp's low morale, telling him they could win. Robert Bruce decided to launch a full-scale attack on the English forces the next day and to use his schiltrons as offensive units, as he had trained them. This was a strategy his predecessor William Wallace had not employed. The English army was defeated in a pitched battle which resulted in the deaths of several prominent commanders, including the Earl of Gloucester and Sir Robert Clifford, and capture of many others, including the Earl of Hereford.[10]

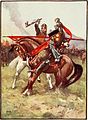

The victory against the English at Bannockburn is one of the most celebrated in Scottish history, and for centuries the battle has been commemorated in verse and art. The National Trust for Scotland operates the Bannockburn Visitor Centre (previously known as the Bannockburn Heritage Centre). Though the exact location for the battle is uncertain, a modern monument was erected in a field above a possible site of the battlefield, where the warring parties are believed to have camped, alongside a statue of Robert Bruce designed by Pilkington Jackson. The monument, along with the associated visitor centre, is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the area.

Background[edit]

Edward I had wanted to expand England to prevent a foreign power such as France from capturing territories in the British Isles. But he needed Scotland's allegiance, which led to his campaign to capture Scotland.[13] The Wars of Scottish Independence between England and Scotland began in 1296. Initially, the English were successful under the command of Edward I: they won victories at the Battle of Dunbar (1296) and at the Capture of Berwick (1296).[14] The removal of John Balliol from the Scottish throne also contributed to the English success.[14] However, the Scots defeated the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. This was countered by Edward I's victory at the Battle of Falkirk (1298).[14] By 1304, Scotland had been conquered, but in 1306 Robert the Bruce seized the Scottish throne and the war was reopened.[14]

After the death of Edward I in 1307, his son Edward II of England was crowned as king, but was incapable of providing the determined leadership his father had shown, and the English position soon became more difficult.[14]

In 1313, Bruce demanded the allegiance of all remaining Balliol supporters, under threat of losing their lands. He also demanded the surrender of the English garrison at Stirling Castle,[10] one of the most important castles held by the English, as it commanded the route north into the Scottish Highlands.[14] It was besieged in 1314 by Bruce's younger brother Edward Bruce, and the English decided that if the castle was not relieved by mid-summer it would be surrendered to the Scots.[14]

The English could not ignore this challenge, and prepared and equipped a substantial campaign. Edward II requested from England, Wales and Ireland 2,000 heavily armoured cavalry and 13,000 infantry. It is estimated that no more than half the infantry actually arrived, but the English army was still by far the largest ever to invade Scotland. The Scottish army probably numbered around 7,000 men,[10] including no more than 500 mounted troops.[14] Unlike the English, the Scottish cavalry was probably not equipped for charging enemy lines and suitable only for skirmishing and reconnaissance. The Scottish infantry was likely armed with axes, swords and pikes, and included only a few bowmen.[14]

The precise numerical advantage of the English forces relative to the Scottish forces is unknown, but modern researchers estimate that the Scottish faced English forces one-and-a-half to three times their number.[15]

Battle[edit]

Location of the battlefield[edit]

The exact site of the Battle of Bannockburn has been debated for many years,[22] but most modern historians agree that the traditional site,[23] where a visitor centre and statue have been erected, is not correct.[24]

A large number of alternative locations have been considered, but modern researchers believe only two merit serious consideration:[25]

Aftermath[edit]

The immediate aftermath was the surrender of Stirling Castle, one of Scotland's most important fortresses, to King Robert. He then slighted (razed) it to prevent it from being retaken. Nearly as important was the surrender of Bothwell Castle, where a sizeable party of English nobles, including the Earl of Hereford, had taken refuge.[45] At the same time the Edwardian strongholds of Dunbar and Jedburgh were also being captured. By 1315, only Berwick remained outside of Robert's control.[46] In exchange for the captured nobles, Edward II released Robert's wife Elizabeth de Burgh, sisters Christina Bruce, Mary Bruce and daughter Marjorie Bruce, and Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow, ending their eight-year imprisonment in England. Following the battle, King Robert rewarded Sir Gilbert Hay of Erroll with the office of hereditary Lord High Constable of Scotland.

The defeat of the English opened up the north of England to Scottish raids[14] and allowed the Scottish invasion of Ireland.[39] These finally led, after the failure of the Declaration of Arbroath to secure diplomatic recognition of Scotland's independence by the Pope, to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328.[39] Under the treaty, the English crown recognised the independence of the Kingdom of Scotland, and acknowledged Robert the Bruce as the rightful king.[47]