Belfast

Belfast (/ˈbɛlfæst/ ⓘ BEL-fast, /-fɑːst/ -fahst[a] (from Irish: Béal Feirste [bʲeːlˠ ˈfʲɛɾˠ(ə)ʃtʲə]))[5][6] is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel. It is second to Dublin as the largest city on the island of Ireland with a population in 2021 of 345,418[7] and a metro area population of 671,559.[8]

This article is about the city in Northern Ireland. For other uses, see Belfast (disambiguation).Belfast

51.16[1] sq mi (132.5 km2)

Metropolitan area:

671,559 (2011)[2]

Local Government District:

345,418 (2021)[3]

City Limits:

293,298 (2021)[4]

United Kingdom

BELFAST

028

Established as an English settlement early in the 17th century, its growth was driven by an influx of Scottish-descendant Presbyterians. Their disaffection with Ireland's Anglican establishment contributed to the rebellion of 1798, and to the union with Great Britain—later regarded as a key to the town's industrial transformation. When granted city status in 1888, Belfast was the world's largest centre of linen manufacture, and by the 1900s her shipyards were building up to a quarter of total United Kingdom tonnage.

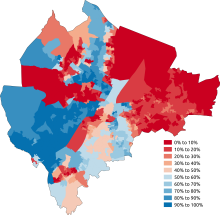

Sectarian tensions accompanied the growth of an Irish Catholic population drawn by mill and factory employment from western districts. Heightened by division over Ireland's future in the United Kingdom, these twice erupted in periods of sustained violence: in 1920-22, as Belfast emerged as the capital of the six northeast counties retaining the British connection, and over three decades from the late 1960s during which the British Army was continually deployed on the streets. A legacy of conflict is the barrier-reinforced separation of Protestant and Catholic working-class districts.

Since the 1998 Belfast Agreement, the electoral balance in the once unionist-controlled city has shifted, albeit with no overall majority, in favour of Irish nationalists. At the same time, new immigrants are adding to the growing number of residents unwilling to identify with either of the two communal traditions.

Belfast has seen significant services sector growth, with important contributions from financial technology (fintech), from tourism and, with facilities in the redeveloped Harbour Estate, from film. It retains a port with commercial and industrial docks, including a reduced Harland & Wolff shipyard and aerospace and defence contractors. Post Brexit, Belfast and Northern Ireland remain, uniquely, within both the British domestic and European Single trading areas for goods.

The city is served by two airports: George Best Belfast City Airport on the Lough shore and Belfast International Airport 15 miles (24 kilometres) west of the city. It supports two universities: on the north-side of the city centre, Ulster University, and on the southside the longer established Queens University. Since 2021, Belfast has been a UNESCO designated City of Music.

In 2021, there were 345,418 residents within the expanded 2015 Belfast local government boundary[7] and 634,600 in the Belfast Metropolitan Area,[226] approximately one third of Northern Ireland's 1.9 million population.

As with many cities, Belfast's inner city is currently characterised by the elderly, students and single young people, while families tend to live on the periphery. Socio-economic areas radiate out from the Central Business District, with a pronounced wedge of affluence extending out the Malone Road and Upper Malone Road to the south.[227] Deprivation levels are notable in the inner parts of the north and the west of the city. The areas around the Falls Road, Ardoyne and New Lodge (Catholic nationalist) and the Shankill Road (Protestant loyalist) experience some of the highest levels of social deprivation including higher levels of ill health and poor access to services. These areas remain firmly segregated, with 80 to 90 percent of residents being of the one religious designation.[228][229]

Consistent with the trend across all of Northern Ireland, the Protestant population within the city has been in decline, while the non-religious, other religious and Catholic population has risen. The 2021 census recorded the following: 43% of residents as Catholic, 12% as Presbyterian, 8% as Church of Ireland, 3% as Methodist, 6% as belonging to other Christian denominations, 3% to other religions and 24% as having either no religion or no declared religion.[157]

In terms of community background, 47.93% were deemed to belong to, or to have been brought up in, the Catholic faith and 36.45% in a Protestant or other Christian-related denomination.[230] The comparable figures in 2011 were 48.60% Catholic and 42.28% Protestant or other Christian-related denomination.[231]

With respondents free to indicate more than one national identity, in 2021 the largest national identity group was "Irish only" with 35% of the population, followed by "British only" 27%, "Northern Irish only" 17%, "British and "Northern Irish only" 7%, "Irish and Northern Irish only" 2%, "British, Irish and Northern Irish only" 2%, British and Irish less than 1% and Other identities with 10%.[157]

From the mid to late 19th century, there was a community of central European Jews[232] (among its distinguished members, Hamburg-born Gustav Wilhelm Wolff of Harland & Wolff) and of Italians[233] in Belfast.[234] Today, the largest immigrant groups are Poles, Chinese and Indians.[235][236] The 2011 census figures recorded a total non-white population of 10,219 or 3.3%,[236] while 18,420 or 6.6%[235] of the population were born outside the UK and Ireland.[235] Almost half of those born outside the British Isles lived in south Belfast, where they comprised 9.5% of the population.[235] The majority of the estimated 5,000 Muslims[237] and 200 Hindu families[238] living in Northern Ireland resided in the Greater Belfast area. In the 2021 census the percentage of the city's residents born outside the United Kingdom had risen to 9.8.[87]

Infrastructure[edit]

Hospitals[edit]

The Belfast Health & Social Care Trust is one of five trusts that were created on 1 April 2007 by the Department of Health. Belfast contains most of Northern Ireland's regional specialist centres.[302]

The Royal Hospitals site in west Belfast (junction of Grosvenor and Falls roads) contains two hospitals. The Royal Victoria Hospital (its origins in a number of successive institutions, beginning in 1797 with The Belfast Fever Hospital)[303] provides both local and regional services. Specialist services include cardiac surgery, critical care and the Regional Trauma Centre.[304] The Children's Hospital (Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children) provides general hospital care for children in Belfast and provides most of the paediatric regional specialities.[305]

The Belfast City Hospital (evolved from a 19th-century workhouse and infirmary)[306] on the Lisburn Road is the regional specialist centre for haematology and is home to a najor cancer centre.[307] The Mary G McGeown Regional Nephrology Unit at the City Hospital is the kidney transplant centre and provides regional renal services for Northern Ireland.[308]

Musgrave Park Hospital in south Belfast specialises in orthopaedics, rheumatology, sports medicine and rehabilitation. It is home to Northern Ireland's first Acquired Brain Injury Unit.[309]

The Mater Hospital (founded in 1883 by the Sisters of Mercy)[310] on the Crumlin Road provides a wide range of services, including acute inpatient, emergency and maternity services, to north Belfast and the surrounding areas.[311]

The Ulster Hospital, Upper Newtownards Road, Dundonald, on the eastern edge of the city, first founded as the Ulster Hospital for Women and Sick Children in 1872,[312] is the major acute hospital for the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust. It delivers a full range of outpatient, inpatient and daycare medical and surgical services.[313]

Recreation and sports[edit]

Leisure centres[edit]

Belfast City Council owns and maintains 17 leisure centres across the city, run on its behalf by the non-profit social enterprise GLL under the ‘Better’ brand.[327] These include eight large multipurposed centres complete with swimming pools: Ballysillan Leisure Centre and Grove Wellbeing Centre in North Belfast; the Andersonstown, Falls, Shankill and Whiterock leisure centres in West Belfast; Templemore Baths and Lisnasharragh Leisure Centre in East Belfast, and close to the city centre in South Belfast, the Olympia Leisure Centre and Spa,[328]

Belfast City Council takes part in the twinning scheme,[365] and is twinned with the following sister cities:

Those who have received the Freedom of the City[367]