Billy Budd

Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative), also known as Billy Budd, Foretopman, is a novella by American writer Herman Melville, left unfinished at his death in 1891. Acclaimed by critics as a masterpiece when a hastily transcribed version was finally published in 1924, it quickly took its place as a classic second only to Moby-Dick among Melville's works. Billy Budd is a "handsome sailor" who strikes and inadvertently kills his false accuser, Master-at-arms John Claggart. The ship's Captain, Edward Vere, recognizes Billy's lack of intent, but claims that the law of mutiny requires him to sentence Billy to be hanged.

For other uses, see Billy Budd (disambiguation).Author

United States, England

English

- London: Constable & Co.

- Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- 1924 (London)

- 1962 (Chicago)

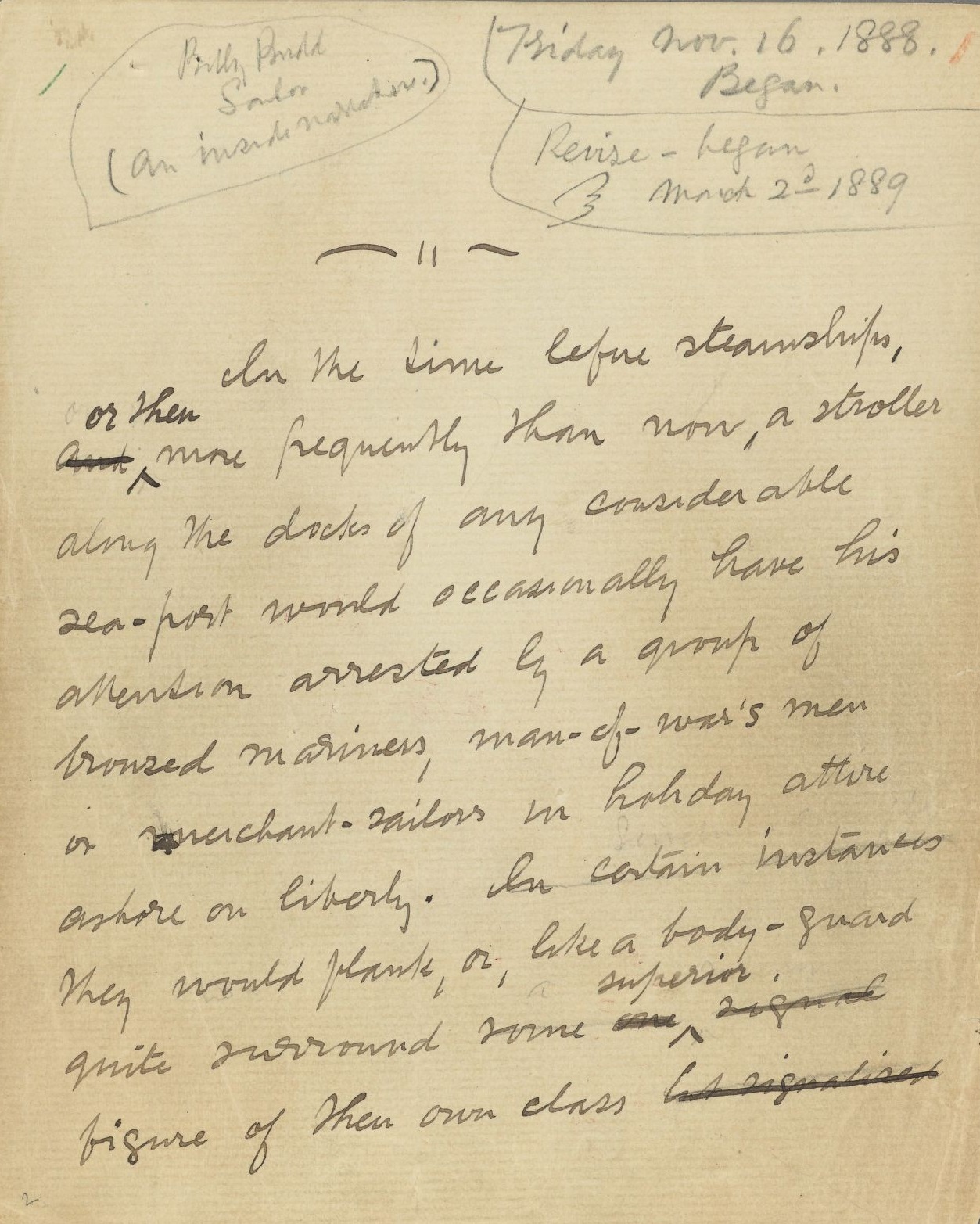

Melville began work on the novella in November 1886, revising and expanding it from time to time, but he left the manuscript in disarray. Melville's widow Elizabeth began to edit the manuscript for publication, but was not able to discern her husband's intentions at key points, even as to the book's title. Raymond M. Weaver, Melville's first biographer, was given the manuscript and published the 1924 version, which was marred by misinterpretation of Elizabeth's queries, misreadings of Melville's difficult handwriting, and even inclusion of a preface Melville had cut. Melville scholars Harrison Hayford and Merton M. Sealts Jr. published what is considered the best transcription and critical reading text in 1962.[1] In 2017, Northwestern University Press published a "new reading text" based on a "corrected version" of Hayford and Sealts' genetic text prepared by G. Thomas Tanselle.[2]

Billy Budd has been adapted into film, a stage play, and an opera.

Billy Budd is a seaman impressed into service aboard HMS Bellipotent in the year 1797, when the Royal Navy was reeling from two major mutinies and was threatened by the Revolutionary French Republic's military ambitions. He is impressed to this large warship from another, smaller, merchant ship, The Rights of Man (named after the book by Thomas Paine). As his former ship moves off, Budd shouts, "And good-bye to you too, old Rights-of-Man."

Billy, a foundling from Bristol, has an innocence, good looks and a natural charisma that make him popular with the crew. He has a stutter, which becomes more noticeable when under intense emotion. He arouses the antagonism of the ship's master-at-arms, John Claggart. Claggart, while not unattractive, seems somehow "defective or abnormal in the constitution", possessing a "natural depravity." Envy is Claggart's explicitly stated emotion toward Budd, foremost because of his "significant personal beauty," and also for his innocence and general popularity. (Melville further opines that envy is "universally felt to be more shameful than even felonious crime.") This leads Claggart to falsely charge Billy with conspiracy to mutiny. When the captain, Edward Fairfax "Starry" Vere, is presented with Claggart's charges, he summons Claggart and Billy to his cabin for a private meeting. Claggart makes his case and Billy, astounded, is unable to respond, due to his stutter. In his extreme frustration he strikes out at Claggart, killing him instantly.

Vere convenes a drumhead court-martial. He acts as convening authority, prosecutor, defense counsel and sole witness (except for Billy). He intervenes in the deliberations of the court-martial panel to persuade them to convict Billy, despite their and his beliefs in Billy's moral innocence. (Vere says in the moments following Claggart's death, "Struck dead by an angel of God! Yet the angel must hang!") Vere claims to be following the letter of the Mutiny Act and the Articles of War.

Although Vere and the other officers did not believe Claggart's charge of conspiracy and think Billy justified in his response, they find that their own opinions matter little. The martial law in effect states that during wartime the blow itself, fatal or not, is a capital crime. The court-martial convicts Billy following Vere's argument that any appearance of weakness in the officers and failure to enforce discipline could stir more mutiny throughout the British fleet. Condemned to be hanged the morning after his attack on Claggart, Billy's last words prior to his execution are "God bless Captain Vere!", which are repeated by the gathered crew in a "resonant and sympathetic echo."CH 26

The novel closes with three short chapters that present ambiguity:

Literary significance and reception[edit]

The book has undergone a number of substantial, critical reevaluations in the years since its discovery. Raymond Weaver, its first editor, was initially unimpressed and described it as "not distinguished". After its publication debut in England, and with critics of such caliber as D. H. Lawrence and John Middleton Murry hailing it as a masterpiece, Weaver changed his mind. In the introduction to its second edition in the 1928 Shorter Novels of Herman Melville, he declared: "In Pierre, Melville had hurled himself into a fury of vituperation against the world; with Billy Budd he would justify the ways of God to man." German novelist Thomas Mann declared that Billy Budd was "one of the most beautiful stories in the world" and that it "made his heart wide open"; he declared that he wished he had written the scene of Billy's dying.[10]

In mid-1924 Murry orchestrated the reception of Billy Budd, Foretopman, first in London, in the influential Times Literary Supplement, in an essay called "Herman Melville's Silence" (July 10, 1924), then in a reprinting of the essay, slightly expanded, in The New York Times Book Review (August 10, 1924). In relatively short order he and several other influential British literati had managed to canonize Billy Budd, placing it alongside Moby-Dick as one of the great books of Western literature. Wholly unknown to the public until 1924, Billy Budd by 1926 had joint billing with the book that had just recently been firmly established as a literary masterpiece. In its first text and subsequent texts, and as read by different audiences, the book has kept that high status ever since.[1]

In 1990 the Melville biographer and scholar Hershel Parker pointed out that all the early estimations of Billy Budd were based on readings from the flawed transcription texts of Weaver. Some of these flaws were crucial to an understanding of Melville's intent, such as the famous "coda" at the end of the chapter containing the news account of the death of the "admirable" John Claggart and the "depraved" William Budd (25 in Weaver, 29 in Hayford & Sealts reading text, 344Ba in the genetic text) :

Weaver: "Here ends a story not unwarranted by what happens in this incongruous world of ours—innocence and 'infirmary', spiritual depravity and fair 'respite'."

The Ms: "Here ends a story not unwarranted by what happens in this {word undeciphered} world of ours—innocence and 'infamy', spiritual depravity and fair 'repute'."

Melville had written this as an end-note after his second major revision. When he enlarged the book with the third major section, developing Captain Vere, he deleted the end-note, as it no longer applied to the expanded story. Many of the early readers, such as Murry and Freeman, thought this passage was a foundational statement of Melville's philosophical views on life. Parker wonders what they could possibly have understood from the passage as printed.[6]

Adaptations for cinema and television: