Boreal forest of Canada

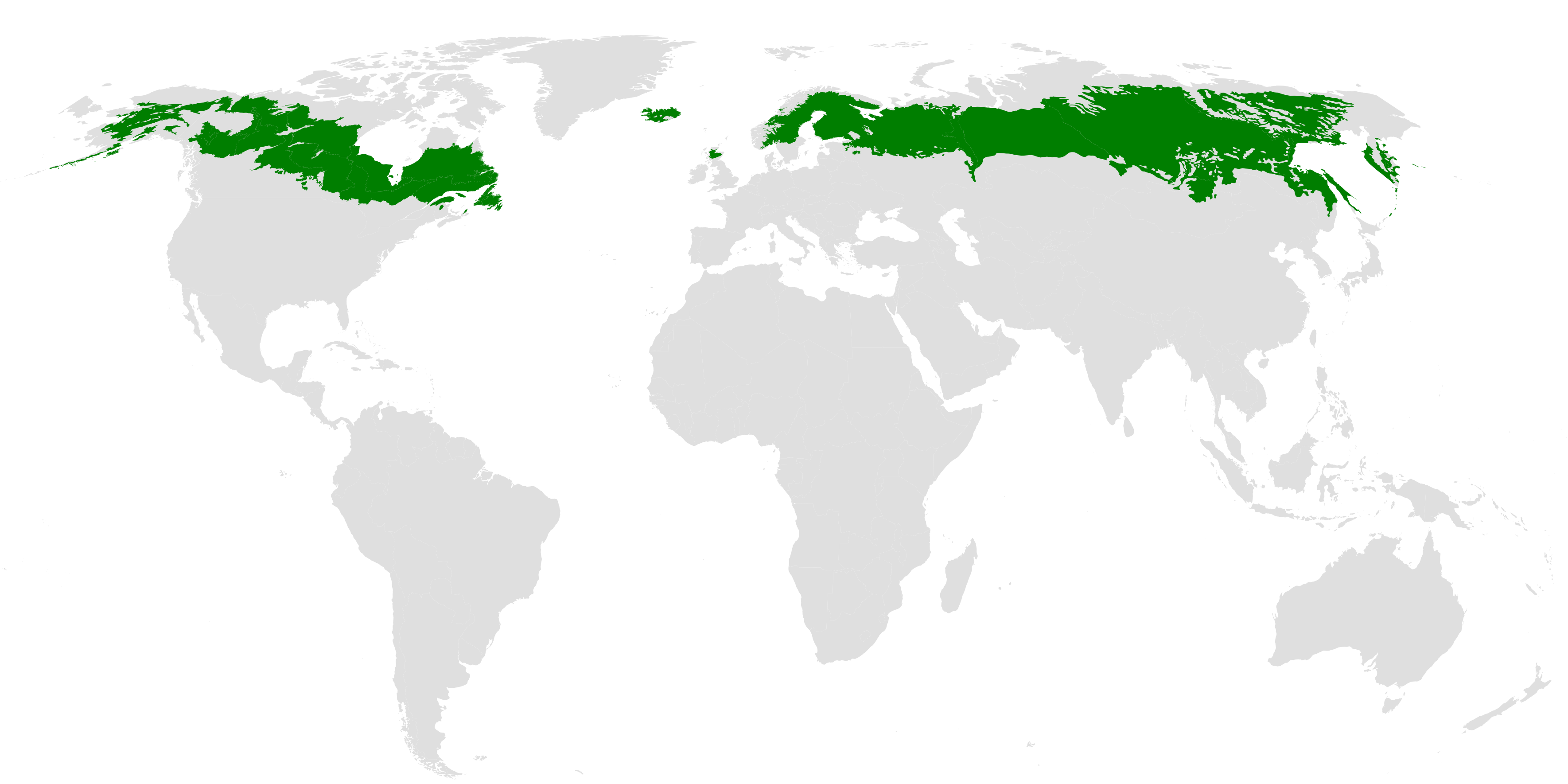

Canada's boreal forest is a vast region comprising about one third of the circumpolar boreal forest that rings the Northern Hemisphere, mostly north of the 50th parallel.[1] Other countries with boreal forest include Russia, which contains the majority; the United States in its northernmost state of Alaska; and the Scandinavian or Northern European countries (e.g. Sweden, Finland, Norway and small regions of Scotland). In Europe, the entire boreal forest is referred to as taiga, not just the northern fringe where it thins out near the tree line. The boreal region in Canada covers almost 60% of the country's land area.[2] The Canadian boreal region spans the landscape from the most easterly part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador to the border between the far northern Yukon and Alaska. The area is dominated by coniferous forests, particularly spruce, interspersed with vast wetlands, mostly bogs and fens. The boreal region of Canada includes eight ecozones. While the biodiversity of regions varies, each ecozone has a characteristic native flora and fauna.[3]

The boreal forest zone consists of closed-crown conifer forests with a conspicuous deciduous element (Ritchie 1987).[4] The proportions of the dominant conifers (white and black spruces, jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.), tamarack, and balsam fir) vary greatly in response to interactions among climate,[5] topography, soil, fire, pests, and perhaps other factors.

The boreal region contains about 13% of Canada's population. With its sheer vastness and forest cover, the boreal makes an important contribution to the rural and aboriginal economies of Canada, primarily through resource industries, recreation, hunting, fishing and eco-tourism. Hundreds of cities and towns within its territory derive at least 20% of their economic activity from the forest, mainly from industries like forest products, mining, oil and gas and tourism.[6] The boreal forest also plays an iconic role in Canada's history, economic and social development and the arts.[7]

Overview[edit]

Location and size[edit]

The Canadian boreal forest is a very large bio-region that extends in length from the Yukon-Alaska border right across the country to Newfoundland and Labrador. It is over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) in width (north to south) separating the arctic tundra region from the various landscapes of southern Canada. The taiga growth (as defined in North America) along the northern flank of the boreal forest creates a transition to the tundra region at the northern tree line. On the southwestern flank, the boreal forest extends into sub-alpine and lower elevation areas of northern British Columbia. The central interior of the province is occupied by a sub-boreal transition zone between the main boreal forest and the dry forests of the southern interior.[8] However, across the Prairie Provinces, a band of aspen parkland marks a different kind of transition along the south-central flank from boreal forest to grassland. In Central Canada, the southeastern flank is marked by the Eastern forest-boreal transition of Central Ontario and western Quebec. It consists mainly of mixed coniferous and broad-leaf woodlands. South of this transition can be found the deciduous woodlands of Southern Ontario.

Canada's boreal forest is considered to be the largest intact forest on Earth, with around three million square kilometres still undisturbed by roads, cities and industrial development.[9] Its high level of intactness has made the forest a particular focus of environmentalists and conservation scientists who view the untouched regions of the forest as an opportunity for large-scale conservation that would otherwise be impractical in other parts of the world.

General forest ecology[edit]

The Canadian boreal forest in its current form began to emerge with the end of the last Ice Age. With the retreat of the Wisconsin Ice Sheet 10,000 years ago, spruce and northern pine migrated northward and were followed thousands of years later by fir and birch.[10] About 5,000 years ago, the Canadian boreal began to resemble what it is today in terms of species composition and biodiversity. This type of coniferous forest vegetation is spread across the Northern Hemisphere. These forests contain three structural types: forest tundra in the north, open lichen woodland further south, and closed forest in more southern areas.[11] White spruce, black spruce and tamarack are most prevalent in the four northern eco-zones of the Taiga and Hudson Plains, while spruce, balsam fir, jack pine, white birch and trembling aspen are most common in the lower boreal regions. Large populations of trembling aspen and willow are found in the southernmost parts of the Boreal Plains.[12]

One dominant characteristic of the boreal is that much of it consists of large, even-aged stands, a uniformity that owes to a cycle of natural disturbances like forest fires, or outbreaks of pine beetle or spruce budworm that kill large tracts of forest with cyclical regularity.[11][13] For example, the many stands of white spruce, black spruce, and balsam fir are vulnerable to the cyclical outbreaks of a species of the spruce budworm, the Choristoneura fumiferana.[14][15] Since the melting of the great ice sheet, the boreal forest has been through many cycles of natural death through fire, insect outbreaks and disease, followed by regeneration. Prior to European colonization of Canada and the application of modern firefighting equipment and techniques, the natural burn/regeneration cycle was less than 75 to 100 years, and it still is in many areas.[16]

Terms like old growth and ancient forest have a different connotation in the boreal context than they do when used to describe mature coastal rain forests with longer-lived species and different natural disturbance cycles. However, the effects of forest fires and insect outbreaks differ from the effects of logging, so they should not be treated as equivalent in their ecological consequences. Logging, for example, requires road networks with their negative impacts,[17] and it removes nutrients from the site, which may deplete nutrients for the next cycle of forest growth.[11] Fire, on the other hand, recycles nutrients on location (except for some nitrogen), it removes accumulated organic matter and it stimulates reproduction of fire-dependent species.[18][19]

Boreal life cycles[edit]

Carbon Cycling[edit]

The boreal forests keeps large amounts of carbons in biomass, dead organic matter, and soil pools. [43] Due to cold temperatures, significant amounts of carbon stocks have been built up, this combined with the further increasing temperatures and disturbance rates will lead to the high net source of carbon that will remain for more than a hundred years. This will result in global impacts which researchers are still uncertain about.[44] Direct effects of herbivores can lead to boreal landscapes as there may be decreased regeneration in some local forest patches. This is altering the input of soils, which could affect soil compaction, and density, or reduce microbial and nitrogen levels in the soil. At high abundance, large herbivores often choose palatable, fast-growing plants which keep keystone species in boreal forests juvenile, which changes these forests. This moose-led transition in forest age class distribution and composition causes slower increases in net primary production with lower large herbivore populations. This means that they are not only changing boreal forests from carbon sinks to sources over moderate periods.[45] Wildfires have impacts on the forest carbon balance as well, including the combustion emissions and the after effects. [46]

Natural regeneration[edit]

The particular mixture of tree species depends upon factors including soil moisture, soil depth, and organic content. Upland forests can be closely mixed with forested peatlands. The resulting conifer forests are produced by and dependent upon recurring disturbance from storms, fires, floods and insect outbreaks. Owing to the accumulated peat in the soil, and the predominance of coniferous trees, lightning-caused fire has always been a natural part of this forest. It is one of many ecosystems that depend upon such recurring natural disturbance.[47] For example, fire dependent species like lodgepole and jack pine have resin sealed cones. In a fire, the resin melts and the cones open, allowing seeds to scatter so that a new pine forest begins (see also fire ecology). It has been estimated that prior to European settlement, this renewal process occurred on average every 75 to 100 years, creating even-aged stands of forest. Fire continues to cause natural forest disturbance,[48] but fire suppression and clear-cutting has interrupted these natural cycles, leading to significant changes in species composition.[49]

Boreal vegetation never attains stability because of interactions among fire, vegetation, soil–water relationships, frost action, and permafrost (Churchill and Hanson 1958, Spurr and Barnes 1980).[50][51] Wildfires produce a vegetation mosaic supporting an ever-changing diversity of plant and animal populations (Viereck 1973).[52] In the absence of fire, the accumulation of sphagnum peat on level upland sites would eventually oust coniferous vegetation and produce muskeg.

Economic activities[edit]

Region-wide planning[edit]

Because parts of the boreal forest region are found in nearly every province and territory in Canada, there has not been much in the way of coordinated planning to develop the region. Prime Minister Diefenbaker talked of his "northern vision"[55] but little was done to see it come to pass. A proposal was authored by Richard Rohmer in 1967 called Mid-Canada Development Corridor: A Concept and was discussed by officials and politicians but was never implemented. In 2014, John van Nostrand attempted to revive the concept.[56]

In the absence of a nationwide plan, private industry and the provinces have pursued development in particular products or certain regions. These include the Athabasca Oil Sands in Alberta, the Ring of Fire (Northern Ontario), and Quebec's Plan Nord.

Protection[edit]

In July 2008 the Ontario government announced plans to protect 225,000 km2 (87,000 sq mi) of the Northern Boreal lands.[65] In February 2010 the Canadian government established protection for 5,300 square miles (14,000 km2) of boreal forest by creating a new reserve of 4,100 square miles (11,000 km2) in the Mealy Mountains area of eastern Canada and a waterway provincial park of 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2) that follows alongside the Eagle River from headwaters to sea.[66] A report issued in 2011 by the Pew Environment Group described the Canadian boreal forest as the largest natural storage of freshwater in the world.[67][68]

Boreal in culture and popular imagination[edit]

The boreal forest is deeply ingrained in the Canadian identity and the images foreigners have of Canada. The history of the early European fur traders, their adventures, discoveries, aboriginal alliances and misfortunes is an essential part of the popular colonial history of Canada. The canoe, the beaver pelt, the coureur des bois, the voyageurs, the Hudson's Bay Company and the North-West Mounted Police, the construction of Canada's transcontinental railways – all are symbols of Canadian history familiar to school children that are inextricably linked to the boreal forest.

The forest – and boreal species such as the caribou and loon – are or have been featured on Canadian currency. Another iconic and enduring image of the boreal was created by 20th-century landscape painters, most notably from the Group of Seven, who saw the uniqueness of Canada in its boreal vastness. The Group of Seven artists largely portrayed the boreal as natural, pure and unspoiled by human presence or activity and hence only partly a reflection of reality.[69]

![]() Media related to Boreal forest of Canada at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Boreal forest of Canada at Wikimedia Commons