Oral mucosa

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. It comprises stratified squamous epithelium, termed "oral epithelium", and an underlying connective tissue termed lamina propria.[1] The oral cavity has sometimes been described as a mirror that reflects the health of the individual.[2] Changes indicative of disease are seen as alterations in the oral mucosa lining the mouth, which can reveal systemic conditions, such as diabetes or vitamin deficiency, or the local effects of chronic tobacco or alcohol use.[3] The oral mucosa tends to heal faster and with less scar formation compared to the skin.[4] The underlying mechanism remains unknown, but research suggests that extracellular vesicles might be involved.[5]

Oral mucosa

Oral mucosa can be divided into three main categories based on function and histology:

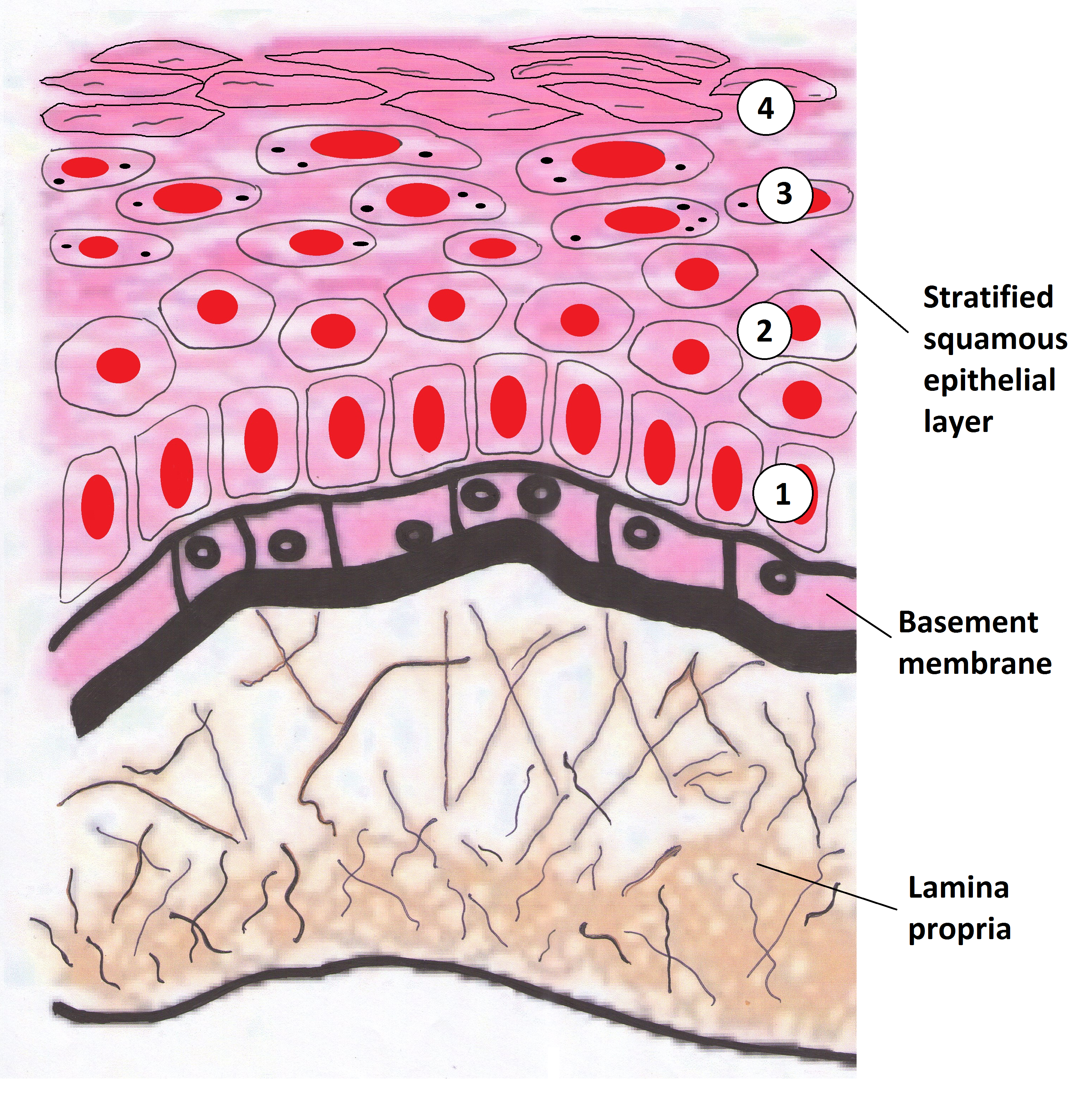

Oral mucosa consists of two layers, the surface stratified squamous epithelium and the deeper lamina propria. In keratinized oral mucosa, the epithelium consists of four layers:

In nonkeratinised epithelium, the two deep layers (basale and spinosum) remain the same but the outer layers are termed the intermediate and superficial layers.

Depending on the region of the mouth, the epithelium may be nonkeratinized or keratinized. Nonkeratinized squamous epithelium covers the soft palate, inner lips, inner cheeks, the floor of the mouth, and ventral surface of the tongue. Keratinized squamous epithelium is present in the gingiva and hard palate as well as areas of the dorsal surface of the tongue.[8][9]

Keratinization is the differentiation of keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum into nonvital surface cells or squames to form the stratum corneum. The cells terminally differentiate as they migrate to the surface from the stratum basale where the progenitor cells are located to the superficial surface.

Unlike keratinized epithelium, nonkeratinized epithelium normally has no superficial layers showing keratinization. Nonkeratinized epithelium may, however, readily transform into a keratinizing type in response to frictional or chemical trauma, in which case it undergoes hyperkeratinization. This change to hyperkeratinization commonly occurs on the usually nonkeratinized buccal mucosa when the linea alba forms, a white ridge of calloused tissue that extends horizontally at the level where the maxillary and mandibular teeth come together and occlude. Histologically, an excess amount of keratin is noted on the surface of the tissue, and the tissue has all the layers of an orthokeratinized tissue with its granular and keratin layers. In patients who have habits such as clenching or grinding (bruxism) their teeth, a larger area of the buccal mucosa than just the linea alba becomes hyperkeratinized. This larger white, rough, raised lesion needs to be recorded so that changes may be made in the dental treatment plan regarding the patient's parafunctional habits.[10][11]

Even keratinized tissue can undergo further level of hyperkeratinization; an increase in the amount of keratin is produced as a result of chronic physical trauma to the region. Changes such as hyperkeratinization are reversible if the source of the injury is removed, but it takes time for the keratin to be shed or lost by the tissue. Thus, to check for malignant changes, a baseline biopsy and microscopic study of any whitened tissue may be indicated, especially if in a high-risk cancer category, such with a history of tobacco or alcohol use or are HPV positive. Hyperkeratinized tissue is also associated with the heat from smoking or hot fluids on the hard palate in the form of nicotinic stomatitis.[10]

The lamina propria is a fibrous connective tissue layer that consists of a network of type I and III collagen and elastin fibers in some regions. The main cells of the lamina propria are the fibroblasts, which are responsible for the production of the fibers as well as the extracellular matrix.

The lamina propria, like all forms of connective tissue proper, has two layers: papillary and dense. The papillary layer is the more superficial layer of the lamina propria. It consists of loose connective tissue within the connective tissue papillae, along with blood vessels and nerve tissue. The tissue has an equal amount of fibers, cells, and intercellular substance. The dense layer is the deeper layer of the lamina propria. It consists of dense connective tissue with a large amount of fibers. Between the papillary layer and the deeper layers of the lamina propria is a capillary plexus, which provides nutrition for the all layers of the mucosa and sends capillaries into the connective tissue papillae.[10]

A submucosa may or may not be present deep in the dense layer of the lamina propria, depending on the region of the oral cavity. If present, the submucosa usually contains loose connective tissue and may also contain adipose tissue or salivary glands, as well as overlying bone or muscle within the oral cavity.[10] The oral mucosa has no muscularis mucosae, and clearly identifying the boundary between it and the underlying tissues is difficult. Typically, regions such as the cheeks, lips, and parts of the hard palate contain submucosa (a layer of loose fatty or glandular connective tissue containing the major blood vessels and nerves supplying the mucosa). The submucosa's composition determines the flexibility of the attachment of oral mucosa to the underlying structures. In regions such as the gingiva and parts of the hard palate, oral mucosa is attached directly to the periosteum of underlying bone, with no intervening submucosa. This arrangement is called a mucoperiosteum and provides a firm, inelastic attachment.[12]

A variable number of Fordyce spots or granules are scattered throughout the nonkeratinized tissue. These are a normal variant, visible as small, yellowish bumps on the surface of the mucosa. They correspond to deposits of sebum from misplaced sebaceous glands in the submucosa that are usually associated with hair follicles.[10]

A basal lamina (basement membrane without aid of the microscope) is at the interface between the oral epithelium and lamina propria similar to the epidermis and dermis.[13]

Mechanical stress is continuously placed on the oral environment by actions such as eating, drinking and talking. The mouth is also subject to sudden changes in temperature and pH meaning it must be able to adapt to change quickly. The mouth is the only place in the body which provides the sensation of taste. Due to these unique physiological features, the oral mucosa must fulfil a number of distinct functions.