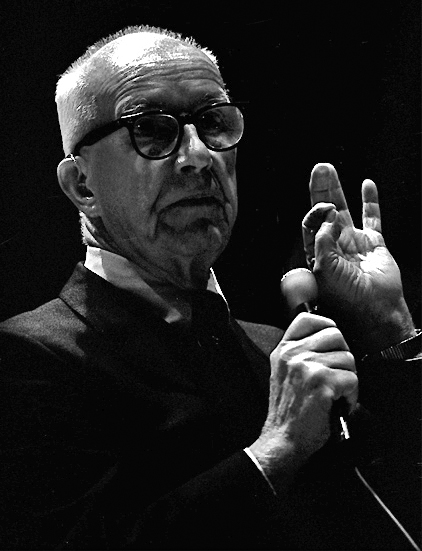

Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (/ˈfʊlər/; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983)[1] was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more than 30 books and coining or popularizing such terms as "Spaceship Earth", "Dymaxion" (e.g., Dymaxion house, Dymaxion car, Dymaxion map), "ephemeralization", "synergetics", and "tensegrity".

For other uses, see Buckminster Fuller (disambiguation).

Buckminster Fuller

July 1, 1983 (aged 87)

- Designer

- author

- inventor

2, including Allegra Fuller Snyder

Geodesic dome (1940s)

Dymaxion house (1928)

Harvard University (expelled)

- Dymaxion Chronofile (1920–1983)

- Nine Chains to the Moon (1938)

- Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968)

- Critical Path (1981)

- Timothy Fuller (great-grandfather)

- Arthur Buckminster Fuller (grandfather)

- Margaret Fuller (grandaunt)

Fuller developed numerous inventions, mainly architectural designs, and popularized the widely known geodesic dome; carbon molecules known as fullerenes were later named by scientists for their structural and mathematical resemblance to geodesic spheres. He also served as the second World President of Mensa International from 1974 to 1983.[2][3]

Fuller was awarded 28 United States patents[4] and many honorary doctorates. In 1960, he was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal from The Franklin Institute. He was elected an honorary member of Phi Beta Kappa in 1967, on the occasion of the 50-year reunion of his Harvard class of 1917 (from which he was expelled in his first year).[5][6] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968.[7] The same year, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member. He became a full Academician in 1970, and he received the Gold Medal award from the American Institute of Architects the same year. Also in 1970, Fuller received the title of Master Architect from Alpha Rho Chi (APX), the national fraternity for architecture and the allied arts.[8]

In 1976, he received the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[9][10] In 1977, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[11] He also received numerous other awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, presented to him on February 23, 1983, by President Ronald Reagan.[12]

Philosophy[edit]

Buckminster Fuller was a Unitarian, and, like his grandfather Arthur Buckminster Fuller (brother of Margaret Fuller),[41][42] a Unitarian minister. Fuller was also an early environmental activist, aware of Earth's finite resources, and promoted a principle he termed "ephemeralization", which, according to futurist and Fuller disciple Stewart Brand, was defined as "doing more with less".[43] Resources and waste from crude, inefficient products could be recycled into making more valuable products, thus increasing the efficiency of the entire process. Fuller also coined the word synergetics, a catch-all term used broadly for communicating experiences using geometric concepts, and more specifically, the empirical study of systems in transformation; his focus was on total system behavior unpredicted by the behavior of any isolated components.

Fuller was a pioneer in thinking globally, and explored energy and material efficiency in the fields of architecture, engineering, and design.[44][45] In his book Critical Path (1981) he cited the opinion of François de Chadenèdes[46] (1920-1999) that petroleum, from the standpoint of its replacement cost in our current energy "budget" (essentially, the net incoming solar flux), had cost nature "over a million dollars" per U.S. gallon ($300,000 per litre) to produce. From this point of view, its use as a transportation fuel by people commuting to work represents a huge net loss compared to their actual earnings.[47] An encapsulation quotation of his views might best be summed up as: "There is no energy crisis, only a crisis of ignorance."[48][49][50]

Though Fuller was concerned about sustainability and human survival under the existing socioeconomic system, he remained optimistic about humanity's future. Defining wealth in terms of knowledge, as the "technological ability to protect, nurture, support, and accommodate all growth needs of life", his analysis of the condition of "Spaceship Earth" caused him to conclude that at a certain time during the 1970s, humanity had attained an unprecedented state. He was convinced that the accumulation of relevant knowledge, combined with the quantities of major recyclable resources that had already been extracted from the earth, had attained a critical level, such that competition for necessities had become unnecessary. Cooperation had become the optimum survival strategy. He declared: "selfishness is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable ... War is obsolete."[51] He criticized previous utopian schemes as too exclusive, and thought this was a major source of their failure. To work, he thought that a utopia needed to include everyone.[52]

Fuller was influenced by Alfred Korzybski's idea of general semantics. In the 1950s, Fuller attended seminars and workshops organized by the Institute of General Semantics, and he delivered the annual Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture in 1955.[53] Korzybski is mentioned in the Introduction of his book Synergetics. The two shared a remarkable amount of similarity in their formulations of general semantics.[54]

In his 1970 book I Seem To Be a Verb, he wrote: "I live on Earth at present, and I don't know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing—a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process—an integral function of the universe."

Fuller wrote that the natural analytic geometry of the universe was based on arrays of tetrahedra. He developed this in several ways, from the close-packing of spheres and the number of compressive or tensile members required to stabilize an object in space. One confirming result was that the strongest possible homogeneous truss is cyclically tetrahedral.[55]

He had become a guru of the design, architecture, and "alternative" communities, such as Drop City, the community of experimental artists to whom he awarded the 1966 "Dymaxion Award" for "poetically economic" domed living structures.

His concepts and buildings include:

In popular culture[edit]

Fuller is quoted in "The Tower of Babble" from the musical Godspell: "Man is a complex of patterns and processes."[135]

Belgian rock band dEUS released the song The Architect, inspired by Fuller, on their 2008 album Vantage Point.[136]

Indie band Driftless Pony Club titled their 2011 album Buckminster after Fuller.[137] Each of the album's songs is based upon his life and works.

The design podcast 99% Invisible (2010–present) takes its title from a Fuller quote: "Ninety-nine percent of who you are is invisible and untouchable."[138]

Fuller is briefly mentioned in X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014) when Kitty Pryde is giving a lecture to a group of students regarding utopian architecture.[139]

Robert Kiyosaki's 2015 book Second Chance[140] concerns Kiyosaki's interactions with Fuller as well as Fuller's unusual final book, Grunch of Giants.[141]

In The House of Tomorrow (2017), based on Peter Bognanni's 2010 novel of the same name, Ellen Burstyn's character is obsessed with Fuller and provides retro-futurist tours of her geodesic home that include videos of Fuller sailing and talking with Burstyn, who had in real life befriended Fuller.

(from the Table of Contents of Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller (1983) ISBN 0-312-43477-4)