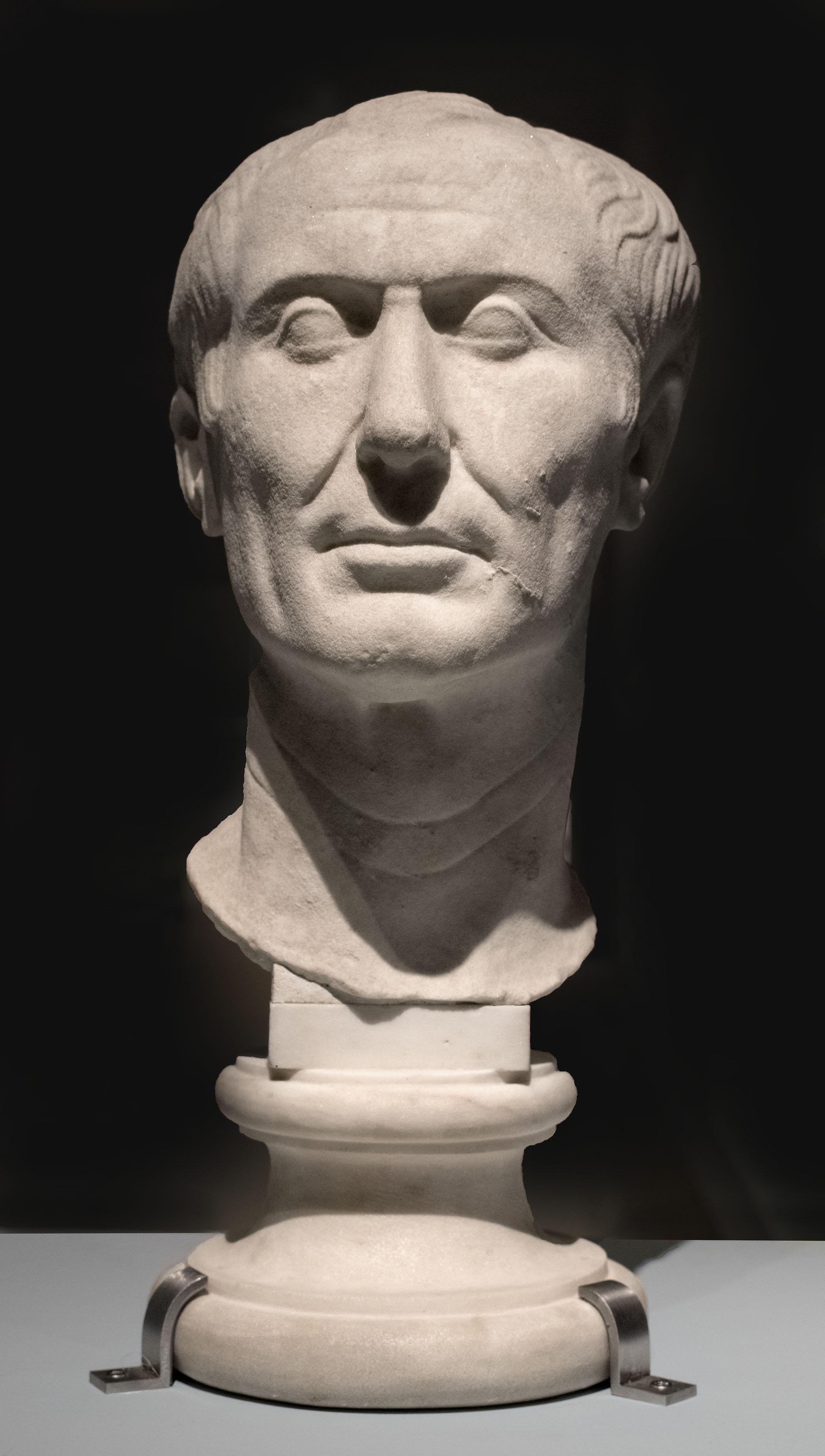

Caesar (title)

Caesar (Latin: [ˈkae̯.sar] English pl. Caesars; Latin pl. Caesares; in Greek: Καῖσαρ Kaîsar) is a title of imperial character. It derives from the cognomen of the Roman dictator Julius Caesar. The change from being a surname to a title used by the Roman emperors can be traced to AD 68, following the fall of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. When used on its own, the title denoted heirs apparent, which would later adopt the title Augustus on accession.[1] The title remained an essential part of the style of the emperors, and became the word for "emperor" in some languages, such as German (kaiser) and Russian (tsar).

Pronunciation

Origins[edit]

The first known individual to bear the cognomen of "Caesar" was Sextus Julius Caesar, who is likewise believed to be the common ancestor of all subsequent Julii Caesares.[2][3] Sextus's great-grandson was the dictator Gaius Julius Caesar, who seized control of the Roman Republic following his war against the Senate. He appointed himself as dictator perpetuo ("dictator in perpetuity"), a title he held for only about a month before he was assassinated in 44 BC. Julius Caesar's death did not lead to the restoration of the Republic, and instead led to the rise of the Second Triumvirate, which was made up of three generals, including Julius' adopted son Gaius Octavius.

Following Roman naming conventions, Octavius adopted the name of his adoptive father, thus also becoming "Gaius Julius Caesar", though he was often called "Octavianus" to avoid confusion. He styled himself simply as "Gaius Caesar" to emphasize his relationship with Julius Caesar.[4] Eventually, distrust and jealousy between the triumvirs led to a lengthy civil war which ultimately ended with Octavius gaining control of the entire Roman world in 30 BC. In 27 BC, Octavius was given the honorific Augustus by the Senate, adopting the name of "Imperator Caesar Augustus". He had previously dropped all his names except for "Caesar", which he treated as a nomen, and had adopted the victory title imperator ("commander") as a new praenomen.[5]

As a matter of course, Augustus's own adopted son and successor, Tiberius, followed his (step)father's example and bore the name "Caesar" following his adoption on 26 June 4 AD, restyling himself as "Tiberius Julius Caesar". Upon his own ascension to the throne, he styled himself as "Tiberius Caesar Augustus". The precedent was thus then set: the Emperor, styled as "Augustus", designated his successor by adopting him and giving him the name "Caesar".

The fourth Emperor, Claudius (in full, "Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus"), was the first to assume the name without having been adopted by the previous emperor. However, he was at least a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, being the maternal great-nephew of Augustus on his mother's side, the nephew of Tiberius, and the uncle of Caligula (who was also called "Gaius Julius Caesar"). Claudius, in turn, adopted his stepson and grand-nephew Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, giving him the name "Caesar" in addition to his own nomen, "Claudius". His stepson thus became "Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus".

Dynastic title[edit]

The first emperor to assume both the position and name without any real claim was Galba, who took the throne under the name "Servius Galba Caesar Augustus" following the death of Nero in AD 68. Galba helped solidify "Caesar" as the title of the designated heir by giving it to his own adopted heir, Piso Licinianus.[6] His reign did not last long, however, and he was soon killed by Otho, who became "Marcus Otho Caesar Augustus". Otho was then defeated by Vitellius, who became "Aulus Vitellius Germanicus Augustus", adopting the victory title "Germanicus" instead. Nevertheless, "Caesar" had become such an integral part of the imperial dignity that its place was immediately restored by Vespasian, who ended the civil war and established the Flavian dynasty in AD 69, ruling as "Imperator Caesar Vespasianus Augustus".[7]

The placement of the name "Caesar" varied among the early emperors. It usually came right before the cognomen (Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Trajan, Hadrian); a few placed it right after it (Galba, Otho, Nerva). The imperial formula was finally standardised during the reign of Antoninus Pius. Antoninus, born "Titus Aurelius Antoninus", became "Titus Aelius Caesar Antoninus" after his adoption but ruled as "Imperator Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius". The imperial formula thus became "Imperator Caesar [name] Augustus" for emperors. Heir-apparents added "Caesar" to their names, placing it after their cognomen.[7] Caesars occasionally were given the honorific princeps iuventutis ("First among the Youth") and, starting with the 3rd century, nobilissimus ("Most Noble").[1]

Later developments[edit]

Crisis of the Third Century[edit]

The popularity of using the title caesar to designate heirs-apparent increased throughout the third century. Many of the soldier-emperors during the Crisis of the Third Century attempted to strengthen their legitimacy by naming their sons as heirs with the title of caesar, namely Maximinus Thrax, Philip the Arab, Decius, Trebonianus Gallus, Gallienus and Carus. With the exception of Verus Maximus and Valerian II all of them were later either promoted to the rank of augustus within their father's lifetime (like Philip II) or succeeded as augusti after their father's death (Hostilian and Numerian). The same title would also be used in the Gallic Empire, which operated autonomously from the rest of the Roman Empire from 260 to 274, with the final Gallic emperor Tetricus I appointing his heir Tetricus II as caesar and his consular colleague.

Despite the best efforts of these emperors, however, the granting of this title does not seem to have made succession in this chaotic period any more stable. Almost all caesares would be killed before, or alongside, their fathers, or, at best, outlive them for a matter of months, as in the case of Hostilian. The sole caesar to successfully obtain the rank of augustus and rule for some time in his own right was Gordian III, and even he was heavily controlled by his court.

Tetrarchy and Diarchy[edit]

In 293, Diocletian established the Tetrarchy, a system of rule by two senior emperors and two junior colleagues. The two coequal senior emperors were styled identically to previous Emperors, as augustus (in plural, augusti). The two junior colleagues were styled identically to previous Emperors-designate, as nobilissimus caesar. Likewise, the junior colleagues retained the title caesar upon becoming full emperors. The caesares of this period are sometimes referred as "emperors", with the Tetrarchy being a "rule of four emperors", despite being clearly subordinate of the augusti and thus not actually sovereigns.[8]

The Tetrarchy collapsed as soon as Diocletian stepped down in 305, resulting in a lengthy civil war. Constantine reunited the Empire 324, after defeating the Eastern emperor Licinius. The tetrarchic division of power was abandoned, although the divisions of the praetorian prefectures were maintained. The title caesar continued to be used, but now merely as a ceremorial honorific for young heirs. Constantine had four caesares at the time of his death: his sons Constantius II, Constantine II, Constans and his nephew Dalmatius, with his eldest son Crispus having been executed in mysterious circumstances earlier in his reign. He would be succeeded only by his three sons, with Dalmatius dying in the summer of 337 in similarly murky circumstances.[9] Constantius II himself would nominate as caesares his cousins Constantius Gallus and Julian in succession in the 350s, although he first executed Gallus and then found himself at war with Julian before his own death. After Julian's revolt of 360, the title fell out of imperial fashion for some time, with emperors preferring simply to elevate their sons directly to augustus, starting with Gratian in 367.[9]

The title would be revived in 408 when Constantine III gave it to his son Constans II,[10] and then in 424 when Theodosius II gave it to his nephew Valentinian III before successfully installing him upon the western throne as augustus in 425.[9] Thereafter it would receive limited use in the Eastern Empire; for example, it was given to Leo II in 472 several months before his grandfather's death. In the Western Empire, Palladius, the son of emperor Petronius Maximus, became the last person bearing the title caesar in 455.

Note: Caesars who later became Augusti and thus emperors are highlighted in bold.