Capital punishment in Canada

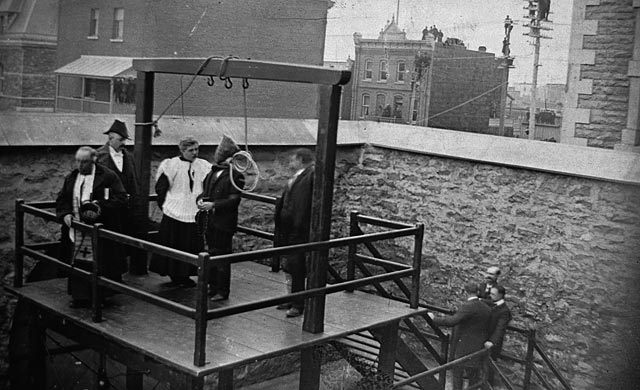

Capital punishment in Canada dates to Canada's earliest history, including its period as first a French then a British colony. From 1867 to the elimination of the death penalty for murder on July 26, 1976, 1,481 people had been sentenced to death, and 710 had been executed. Of those executed, 697 were men and 13 women. The only method used in Canada for capital punishment of civilians after the end of the French regime was hanging. The last execution in Canada was the double hanging of Arthur Lucas and Ronald Turpin on December 11, 1962, at Toronto's Don Jail. The National Defence Act prescribed the death penalty for certain military offences until 1999, although no military executions had been carried out since 1946.

The death penalty was ended in practice in Canada in January 1963 and was abolished in two stages, in 1976 and 1999. Prior to 1976, the death penalty was prescribed under the Criminal Code as the punishment for murder, treason, and piracy. In addition, some service offences under the National Defence Act continued to carry a mandatory death sentence if committed traitorously, although no one had been executed for those offences since 1945. In 1976, Parliament enacted Bill C-48, abolishing the death penalty for murder, treason, and piracy. In 1999, Parliament eliminated the death penalty for the military offences.[1][2]

Public opinion[edit]

Although reintroducing the death penalty in Canada is extremely unlikely,[a] support for capital punishment is similar to its support in the United States,[b] where it is carried out regularly in some states and is on the books in most states and on the federal level. While opposition to the death penalty increased in the 1990s and early 2000s, in recent years, Canadians have moved closer to the American position; in 2004, only 48 percent of Canadians favoured death for murderers compared to 62 percent in 2010.[45] According to one poll, support for the death penalty in Canada is approximately the same as its support in the United States, at 63 percent in both countries as of 2013.[46] A 2012 poll by the Toronto Sun found that 66 percent of Canadians favoured capital punishment, but only 41 percent would actually support its re-introduction in Canada.[47] A 2020 poll by Research Co. found that 51 percent of Canadians are in favour of reinstating the death penalty for murder in their country. However, almost half of Canadians (47%) select life imprisonment without the possibility of parole over the death penalty (34%) as their preferred punishment in cases of murder.[48] A 2023 poll by Research Co. found that 54 percent of Canadians are in favour of reinstating the death penalty for murder in their country.[49] A 2024 poll found 57 percent of Canadians support reinstating the death penalty.[50][51]

Since abolition, only two parties were known to have advocated to bringing it back: the Reform Party of Canada (1988–2000) and the National Advancement Party of Canada (since 2014).

Among the reasons cited for banning capital punishment in Canada were fears about wrongful convictions, concerns about the state taking people's lives, and uncertainty about the death penalty's role as a deterrent for crime. The 1959 conviction of 14-year-old Steven Truscott, who was sentenced to death and whose conviction was later overturned, was a significant impetus toward the abolition of capital punishment.[52] Truscott was sentenced to death for the murder of a classmate. His sentence was later commuted to a life sentence, and in 2007, he was acquitted of the charges (although the appeal court did not state that he was in fact innocent).[53]

Policy regarding foreign capital punishment[edit]

In the 1990s, Canada extradited a criminal, Charles Ng to the United States, even though he appealed to the authorities, as he did not want to potentially face execution.[54]

The Supreme Court of Canada, in the case United States v. Burns, (2001), determined that Canada should not extradite persons to face trial in other countries for crimes punishable by death unless Canada has received an assurance that the foreign state will not apply the death penalty, essentially overruling Kindler v. Canada (Minister of Justice), (1991).[55] This is similar to the extradition policies of other nations such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom, Israel, Mexico, Colombia and Australia, which also refuse to extradite prisoners who may be condemned to death. Extradition where the death penalty is possible was ruled a violation of the European Convention of Human Rights in the case of Soering v United Kingdom outlawing the practice in member states of the Council of Europe, of which all of the European Union member states are part.[56]

In November 2007, Canada's minority Conservative government reversed a longstanding policy of automatically requesting clemency for Canadian citizens sentenced to capital punishment. The ongoing case of Alberta-born Ronald Allen Smith, who has been on death row in the United States since 1982 after being convicted of murdering two people and who continues to seek calls for clemency from the Canadian government, prompted Canadian Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day to announce the change in policy. Day has stated that each situation should be handled on a case-by-case basis. Smith's case resulted in a sharp divide between the Liberals and the Conservatives, with the Liberals passing a motion declaring that the government "should stand consistently against the death penalty, as a matter of principle, both in Canada and around the world". However, an overwhelming majority of Conservatives supported the change in policy.[57]

In a 2011 interview given to Canadian media, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper affirmed his private support for capital punishment by saying, "I personally think there are times where capital punishment is appropriate."[58]