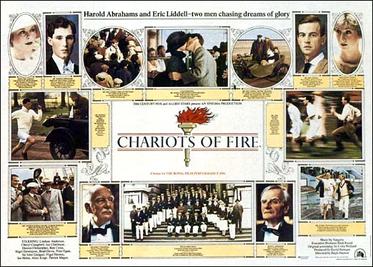

Chariots of Fire

Chariots of Fire is a 1981 British historical sports drama film directed by Hugh Hudson, written by Colin Welland and produced by David Puttnam. It is based on the true story of two British athletes in the 1924 Olympics: Eric Liddell, a devout Scottish Christian who runs for the glory of God, and Harold Abrahams, an English Jew who runs to overcome prejudice. Ben Cross and Ian Charleson star as Abrahams and Liddell, alongside Nigel Havers, Ian Holm, John Gielgud, Lindsay Anderson, Cheryl Campbell, Alice Krige, Brad Davis and Dennis Christopher in supporting roles. Kenneth Branagh makes his debut in a minor role.

This article is about the film. For other uses, see Chariots of Fire (disambiguation).Chariots of Fire

- Allied Stars Ltd

- Enigma Productions

- 30 March 1981 (London)

124 minutes

United Kingdom

English

$59 million (U.S. and Canada)[3]

Chariots of Fire was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Original Score for Vangelis' electronic theme tune. At the 35th British Academy Film Awards, the film was nominated in 11 categories and won in three, including Best Film. It is ranked 19th in the British Film Institute's list of Top 100 British films.

The film's title was inspired by the line "Bring me my Chariot of fire!" from the William Blake poem adapted into the British hymn and unofficial English anthem "Jerusalem"; the hymn is heard at the end of the film.[4] The original phrase "chariot(s) of fire" is from 2 Kings 2:11 and 6:17 in the Bible.

Plot[edit]

During a 1978 funeral service in London in honour of the life of Harold Abrahams, headed by his former colleague Lord Andrew Lindsay, there is a flashback to when he was young and in a group of athletes running along a beach.

In 1919, Harold Abrahams enters the University of Cambridge, where he experiences antisemitism from the staff but enjoys participating in the Gilbert and Sullivan club. He becomes the first person ever to complete the Trinity Great Court Run, running around the college courtyard in the time it takes for the clock to strike 12, and achieves an undefeated string of victories in various national running competitions. Although focused on his running, he falls in love with Sybil Gordon, a leading Gilbert and Sullivan soprano.[a]

Eric Liddell, born in China to Scottish missionary parents, is in Scotland. His devout sister Jennie disapproves of Liddell's plans to pursue competitive running. Still, Liddell sees running as a way of glorifying God before returning to China to work as a missionary. When they first race against each other, Liddell beats Abrahams. Abrahams takes it poorly, but Sam Mussabini, a professional trainer he had approached earlier, offers to take him on to improve his technique. This attracts criticism from the Cambridge college masters, who allege it is not gentlemanly for an amateur to "play the tradesman" by employing a professional coach. Abrahams dismisses this concern, interpreting it as cover for antisemitic and class-based prejudice. When Liddell accidentally misses a church prayer meeting because of his running, Jennie upbraids him and accuses him of no longer caring about God. Eric tells her that though he intends to return eventually to the China mission, he feels divinely inspired when running and that not to run would be to dishonour God.

After years training and racing, the two athletes are accepted to represent Great Britain in the 1924 Olympics in Paris. Also accepted are Abrahams's Cambridge friends, Andrew Lindsay, Aubrey Montague, and Henry Stallard. While boarding the boat to France for the Olympics, Liddell discovers the heats for his 100-metre race will be on a Sunday. Despite intense pressure from the Prince of Wales and the British Olympic Committee, he refuses to run the race because his Christian convictions prevent him from running on the Lord's Day. A solution is found thanks to Liddell's teammate Lindsay, who, having already won a silver medal in the 400 metres hurdles, offers to give his place in the 400-metre race on the following Thursday to Liddell, who gratefully accepts. Liddell's religious convictions in the face of national athletic pride make headlines around the world; he delivers a sermon at the Paris Church of Scotland that Sunday, and quotes from Isaiah 40.

Abrahams is badly beaten by the heavily favoured United States runners in the 200-metre race. He knows his last chance for a medal will be the 100 metres. He competes in the race and wins. His coach Mussabini, who was barred from the stadium, is overcome that the years' dedication and training have paid off with an Olympic gold medal. Now Abrahams can get on with his life and reunite with his girlfriend Sybil, whom he has neglected for the sake of running. Before Liddell's race, the American coach remarks dismissively to his runners that Liddell has little chance of doing well in his new, far longer, 400-metre race. But one of the American runners, Jackson Scholz, hands Liddell a note of support that quotes 1 Samuel 2:30. Liddell defeats the American favourites and wins the gold medal. The British team returns home triumphant.

A textual epilogue reveals that Abrahams married Sybil and became the elder statesman of British athletics while Liddell went on to do missionary work and was mourned by all of Scotland following his death in Japanese-occupied China.

Release[edit]

The film was distributed by 20th Century-Fox and selected for the 1981 Royal Film Performance with its premiere on 30 March 1981 at the Odeon Haymarket before opening to the public the following day. It opened in Edinburgh on 4 April and in Oxford and Cambridge on 5 April[40] with other openings in Manchester and Liverpool before expanding further in May into 20 additional London cinemas and 11 others nationally. It was shown in competition at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival on 20 May.[41]

The film was distributed by The Ladd Company through Warner Bros. in North America and released on 25 September 1981 in Los Angeles, California and in New York Film Festival, on 26 September 1981 in New York and on 9 April 1982 in the United States.[42]

Reception[edit]

Since its release, Chariots of Fire has received generally positive reviews from critics. As of 2022, the film holds an 83% rating from the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 111 reviews, with a weighted average of 7.7/10. The site's consensus reads: "Decidedly slower and less limber than the Olympic runners at the center of its story, Chariots of Fire nevertheless manages to make effectively stirring use of its spiritual and patriotic themes."[43] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 78 out of 100 based on 19 critics' reviews.[44]

For its 2012 re-release, Kate Muir of The Times gave the film five stars, writing: "In a time when drug tests and synthetic fibres have replaced gumption and moral fibre, the tale of two runners competing against each other in the 1924 Olympics has a simple, undiminished power. From the opening scene of pale young men racing barefoot along the beach, full of hope and elation, backed by Vangelis's now famous anthem, the film is utterly compelling."[45]

In its first four weeks at the Odeon Haymarket it grossed £106,484.[46] The film was the highest-grossing British film for the year with theatrical rentals of £1,859,480.[47] Its gross of almost $59 million in the United States and Canada made it the highest-grossing film import into the US (i.e. a film without any US input) at the time, surpassing Meatballs' $43 million.[3][48]

The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning four (including Best Picture). When accepting his Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, Colin Welland famously announced "The British are coming".[49] It was the first film released by Warner Bros. to win Best Picture since My Fair Lady in 1964.

American Film Institute recognition

Other honours