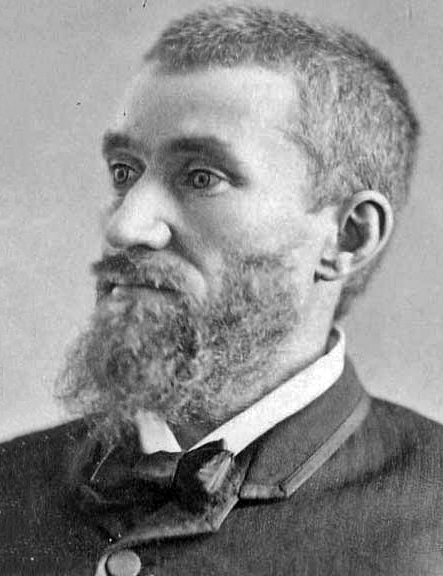

Charles J. Guiteau

Charles Julius Guiteau (/ɡɪˈtoʊ/ ghih-TOH; September 8, 1841 – June 30, 1882) was an American man who assassinated James A. Garfield, president of the United States, in 1881. Guiteau falsely believed he had played a major role in Garfield's election victory, for which he should have been rewarded with a consulship. He felt frustrated and offended by the Garfield administration's rejections of his applications to serve in Vienna or Paris to such a degree that he decided to kill Garfield and shot him at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. Garfield died two months later from infections related to the wounds. In January 1882, Guiteau was sentenced to death for the crime and was hanged five months later.

"Charles Guiteau" redirects here. For the song, see Charles Guiteau (song).

Charles J. Guiteau

June 30, 1882 (aged 40)

- Democratic (1872)

- Republican (Stalwart faction, 1880–1882)

Mental illness possibly related to neurosyphilis, schizophrenia and/or grandiose narcissism; retribution for perceived failure to reward campaign support

James Abram Garfield, aged 49

July 2, 1881

Washington, D.C., U.S.

Early life and education[edit]

Charles J. Guiteau was born in Freeport, Illinois, the fourth of six children of Jane August (née Howe; 1814 – 1848) and Luther Wilson Guiteau (1810 – 1880),[1] whose family was of French Huguenot ancestry.[2] His mother died in 1848, and in 1850 he moved with his family to Ulao, Wisconsin (near current-day Grafton), where he lived until 1855.[3] Soon after, Guiteau and his father moved back to Freeport.[4]

In 1860, Guiteau inherited $1,000 (equivalent to $34,000 in 2023) from his grandfather and planned to attend the University of Michigan but he failed the entrance examinations because of inadequate academic preparation. He crammed in French and algebra at Ann Arbor High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he received numerous letters from his father that extolled the Oneida Community, so he quit school before completing the program. In June 1860 he joined the Oneida Community, the utopian religious sect in Oneida, New York, with which Guiteau's father already had a close affiliation.[5] According to Brian Resnick of The Atlantic, Guiteau "worshiped" the group's founder, John Humphrey Noyes, once writing that he had "perfect, entire and absolute confidence in him in all things".[6][7]

Despite the "group marriage" aspects of the Oneida Community, Guiteau was generally rejected during his five years there and his name was turned into a play on words to create the nickname "Charles Gitout".[8][9] He left the community twice; the first time, he went to Hoboken, New Jersey, and attempted to start a newspaper based on the Oneida religion, called The Daily Theocrat.[5] This failed and he returned to Oneida, only to leave again and file lawsuits against Noyes, in which he demanded payment for the work he had supposedly performed on behalf of the Oneida Community.[7] Guiteau's embarrassed father wrote letters in support of Noyes, who considered Guiteau irresponsible and insane.[10]