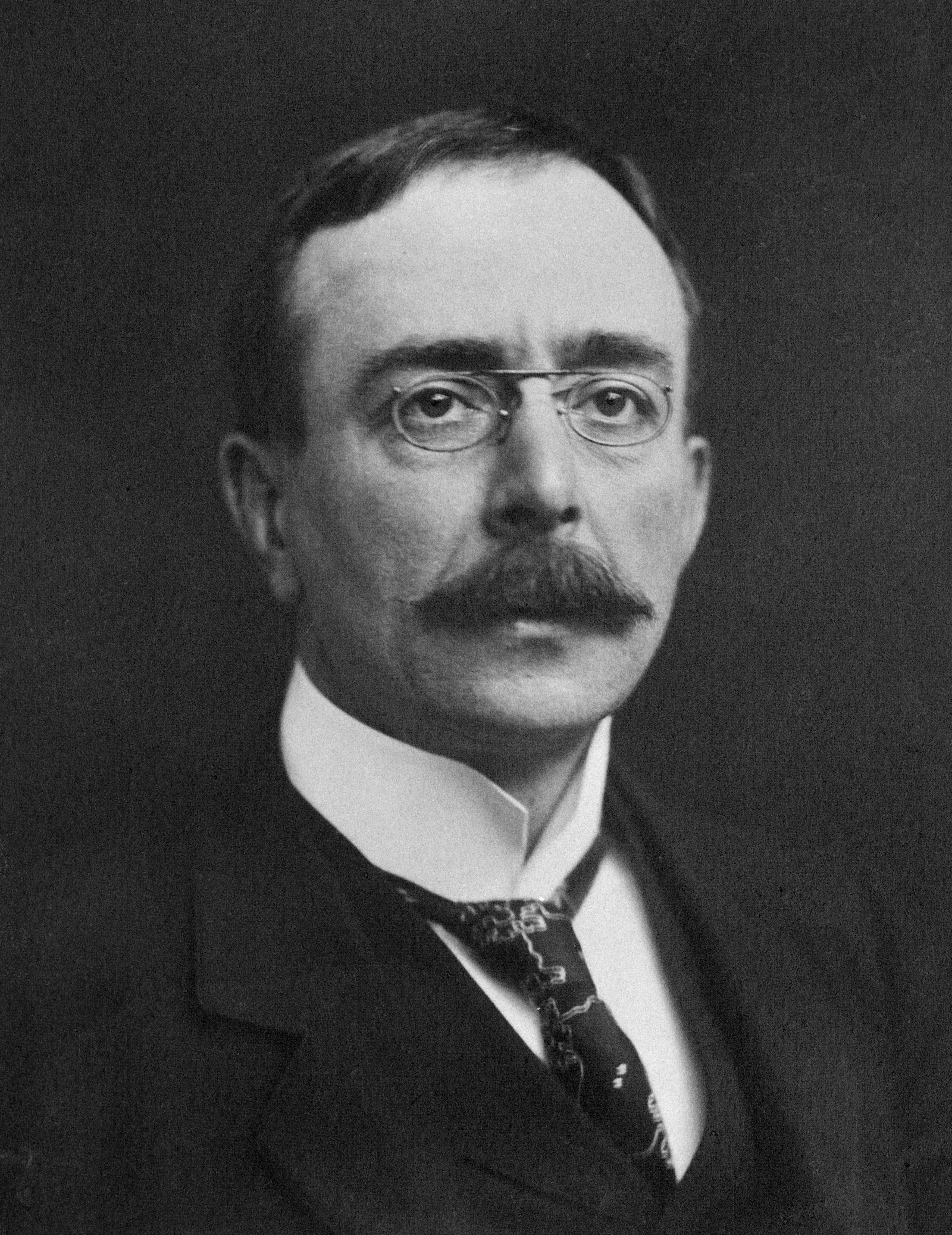

Charles Scott Sherrington

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington OM GBE FRS FRCP FRCS[1][3] (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was a British neurophysiologist. His experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience, including the concept of the spinal reflex as a system involving connected neurons (the "neuron doctrine"), and the ways in which signal transmission between neurons can be potentiated or depotentiated. Sherrington himself coined the word "synapse" to define the connection between two neurons. His book The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (1906)[4] is a synthesis of this work, in recognition of which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1932 (along with Edgar Adrian).[5][6][7][8]

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington

27 November 1857

Islington, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

4 March 1952 (aged 94)

Eastbourne, Sussex, England, United Kingdom

British

- FRS (1893)[1]

- Royal Medal (1905)

- Copley Medal (1927)

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1932)

In addition to his work in physiology, Sherrington did research in histology, bacteriology, and pathology. He was president of the Royal Society in the early 1920s.

Family[edit]

On 27 August 1891, Sherrington married Ethel Mary Wright (died 1933), daughter of John Ely Wright of Preston Manor, Suffolk, England. They had one child, a son named Charles ("Carr") E.R. Sherrington, who was born in 1897.[22]

On weekends during the Oxford years the couple would frequently host a large group of friends and acquaintances at their house for an enjoyable afternoon.[1]

Publications[edit]

The Integrative Action of the Nervous System[edit]

Published in 1906,[4] this was a compendium of ten of Sherrington's Silliman lectures, delivered at Yale University in 1904.[31]

The book discussed neuron theory, the "synapse" (a term he had introduced in 1897, the word itself suggested by classicist A. W. Verrall[32]), communication between neurons, and a mechanism for the reflex-arc function.[7] The work effectively resolved the debate between neuron and reticular theory in mammals, thereby shaping our understanding of the central nervous system.[31]

He theorized that the nervous system coordinates various parts of the body and that the reflexes are the simplest expressions of the interactive action of the nervous system, enabling the entire body to function toward a definite purpose. Sherrington pointed out that reflexes must be goal-directive and purposive. Furthermore, he established the nature of postural reflexes and their dependence on the anti-gravity stretch reflex and traced the afferent stimulus to the proprioceptive end organs, which he had previously shown to be sensory in nature ("proprioceptive" was another term he had coined[7]). The work was dedicated to Ferrier.[22]

The Assaying of Brabantius and other Verse[edit]

This collection of previously published war-time poems was Sherrington's first major poetic release, published in 1925. Sherrington's poetic side was inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Sherrington was fond of Goethe the poet, but not Goethe the scientist. Speaking of Goethe's scientific writings, Sherrington said "to appraise them is not a congenial task."[1]

Man on His Nature[edit]

A reflection on Sherrington's philosophical thought. Sherrington had long studied the 16th century French physician Jean Fernel, and grew so familiar with him that he considered him a friend. During the academic year 1937-38, Sherrington delivered the Gifford lectures at the University of Edinburgh. They focused on Fernel and his times, and formed the basis of Man on His Nature. The book was published in 1940, with a revised edition in 1951. It explores philosophical thoughts about the mind, human existence, and God, in accordance with natural theology.[33] In the original edition, each of the twelve chapters begins with one of the twelve zodiac signs; Sherrington discusses astrology in Fernel's time in Chapter 2.[34] In his ideas on mind and cognition, Sherrington introduced the idea that neurons work as groups in a "million-fold democracy" to produce outcomes rather than with central control.[35]