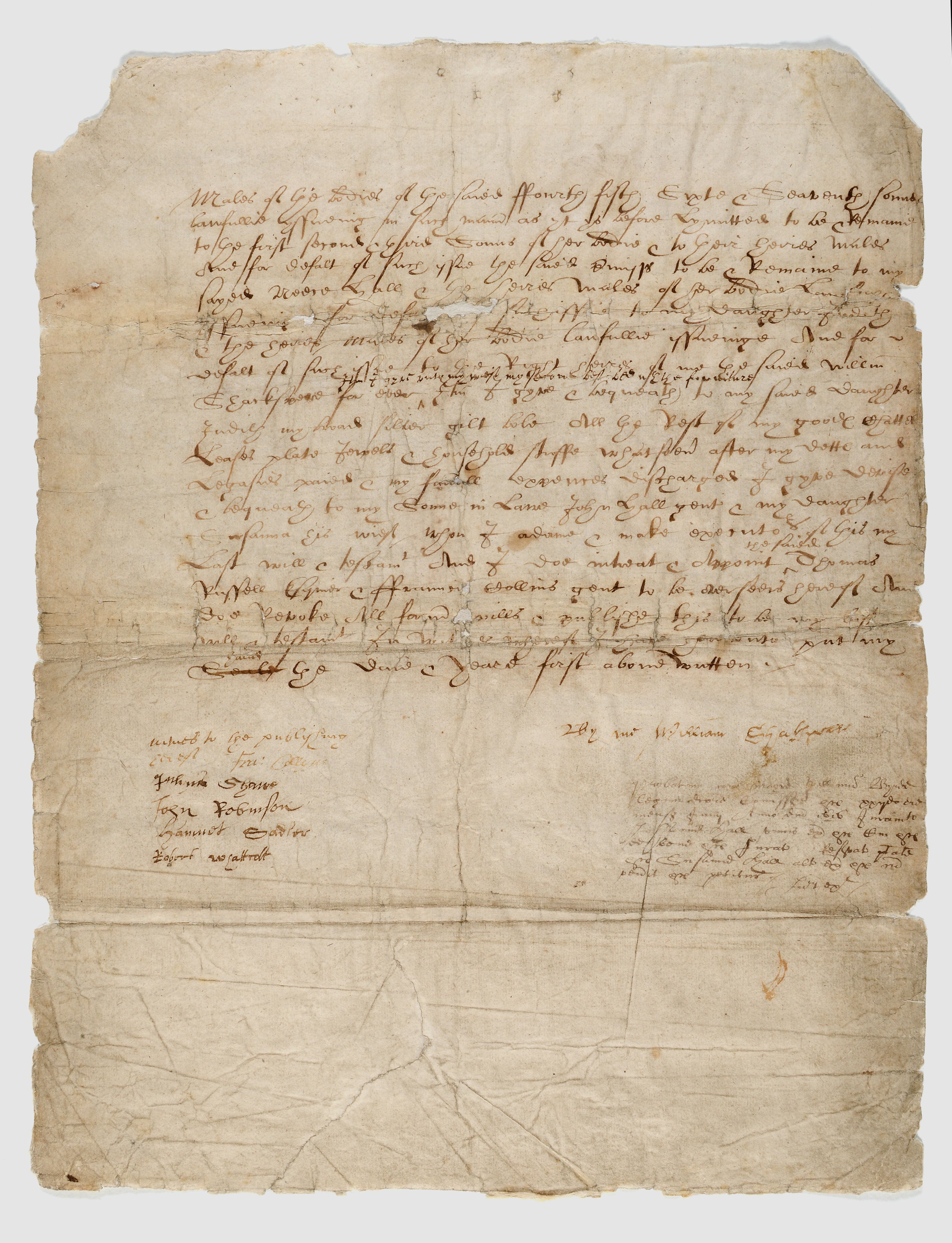

Codicil (will)

A codicil is a testamentary or supplementary document similar but not necessarily identical to a will. The purpose of a codicil can differ across jurisdictions. It may serve to amend, rather than replace, a previously executed will, serve as an alternative or replacement to a will, or in some instances have no recognized distinction between it and a will.

Origins[edit]

The concept of a testamentary document as similar to but distinct from a will originated in Roman law. In the pre-classical period, a testator was required to nominate an heir in order for his will to be valid (heredis institutio).[2] Failure to nominate an heir or failure to observe the proper formalities for nomination of an heir resulted in an estate divided pursuant to the rules of intestacy. However, a testator was also able to institute a fideicommissum, a more flexible and less formal indication of the testator's intent, which could have the effect of transferring part or all of his estate after death, although with fewer rights to the beneficiary than those of a nominated heir.[3]

A codicillus (diminutive of codex)[4] was a written document subject to fewer formal requirements than a will (testamentum) that, in its initial use, could supplement or amend an existing will, provided that the codicil was specified, i. e. confirmed, in the will.[5] However, if the will did not confirm the codicil, all provisions in the codicil were considered fideicommissa. Furthermore, a will that did not nominate an heir could be considered a codicil. Thus, when a testator did not nominate an heir, his will would be considered a codicil and his bequests would become fideicommissa. This "opened a way to save certain dispositions in a will which was invalid due to some formal or substantive defect": if a testator failed or chose not to nominate an heir, an estate would pass to heirs pursuant to rules of intestacy, but those heirs would be bound by the fideicommissa in the codicil.

By the time of the Codex Justinianus, the formal requirements for wills had relaxed, while requirements for codicils had become more stringent. "There was thus little difference between the formalities for a will and for a codicil", and an invalid will, when for example, no heir had been nominated, could often be validated as a codicil.[6]

It is acknowledged that classical Roman inheritance law was "highly complicated and to a large extent perplexedly entangled" (Fritz Schulz).[7]