Crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, later attested to by other ancient sources, and is broadly accepted as one of the events most likely to have occurred during his life.[1] There is no consensus among historians on the details.[2][3][4]

"The Crucifixion" redirects here. For other uses, see Crucifixion (disambiguation).Date

AD 30/33

Condemnation before Pilate's court

Roman army (executioners)

- Ministry of the apostles

- Earliest persecution of Christians

According to the canonical gospels, Jesus was arrested and tried by the Sanhedrin, and then sentenced by Pontius Pilate to be scourged, and finally crucified by the Romans.[5][6][7] The Gospel of John portrays his death as a sacrifice for sin.

Jesus was stripped of his clothing and offered vinegar mixed with myrrh or gall (likely posca[8]), to drink after saying "I am thirsty". At Golgotha, he was then hung between two convicted thieves and, according to the Gospel of Mark, died by the 9th hour of the day (at around 3:00 p.m.). During this time, the soldiers affixed a sign to the top of the cross stating "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" which, according to the Gospel of John (John 19:20), was written in three languages (Hebrew, Latin, and Greek). They then divided his garments among themselves and cast lots for his seamless robe, according to the Gospel of John. The Gospel of John also states that, after Jesus' death, one soldier (named in extra-Biblical tradition as Longinus) pierced his side with a spear to be certain that he had died, then blood and water gushed from the wound. The Bible describes seven statements that Jesus made while he was on the cross, as well as several supernatural events that occurred.

Collectively referred to as the Passion, Jesus's suffering and redemptive death by crucifixion are the central aspects of Christian theology concerning the doctrines of salvation and atonement.

Denial[edit]

Docetism[edit]

In Christianity, docetism is the doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, and above all the human form of Jesus, was mere semblance without any true reality.[236] Docetists denied that Jesus could have truly suffered and died, as his physical body was illusory, and instead saw the crucifixion as something that only appeared to happen.[237]

Nag Hammadi manuscripts[edit]

According to the First Revelation of James in the Nag Hammadi library, Jesus appeared to James after apparently being crucified and stated that another person had been inflicted in his place:

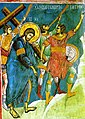

Since the crucifixion of Jesus, the cross has become a key element of Christian symbolism, and the crucifixion scene has been a key element of Christian art, giving rise to specific artistic themes such as Christ Carrying the Cross, raising of the Cross, Stabat Mater, Descent from the Cross and Lamentation of Christ.

The symbolism of the cross which is today one of the most widely recognized Christian symbols was used from the earliest Christian times. Justin Martyr, who died in 165, describes it in a way that already implies its use as a symbol, although the crucifix appeared later.[252][253]

Devotions based on the process of crucifixion, and the sufferings of Jesus are followed by various Christians. The Stations of the Cross follows a number of stages based on the stages involved in the crucifixion of Jesus, while the Rosary of the Holy Wounds is used to meditate on the wounds of Jesus as part of the crucifixion.

Masters such as Giotto, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, Raphael, Botticelli, van Dyck, Titian, Caravaggio, El Greco, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Rubens and Rembrandt have all depicted the crucifixion scene in their works. The Crucifixion, seen from the Cross by Tissot presented a novel approach at the end of the 19th century, in which the crucifixion scene was portrayed from the perspective of Jesus.[254][255]

The presence of the Virgin Mary under the cross, mentioned in the Gospel of John,[256] has in itself been the subject of Marian art, and well known Catholic symbolism such as the Miraculous Medal and Pope John Paul II's Coat of Arms bearing a Marian Cross. And a number of Marian devotions also involve the presence of the Virgin Mary in Calvary, e.g., Pope John Paul II stated that "Mary was united to Jesus on the Cross".[257][258] Well known works of Christian art by masters such as Raphael (the Mond Crucifixion), and Caravaggio (The Entombment of Christ) depict the Virgin Mary as part of the crucifixion scene.

![Crucified Jesus at the Ytterselö church [sv], Sweden. Ca. 1500](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Jesus_Tkors_Ytterselo01.gif/119px-Jesus_Tkors_Ytterselo01.gif)