Elbridge Gerry

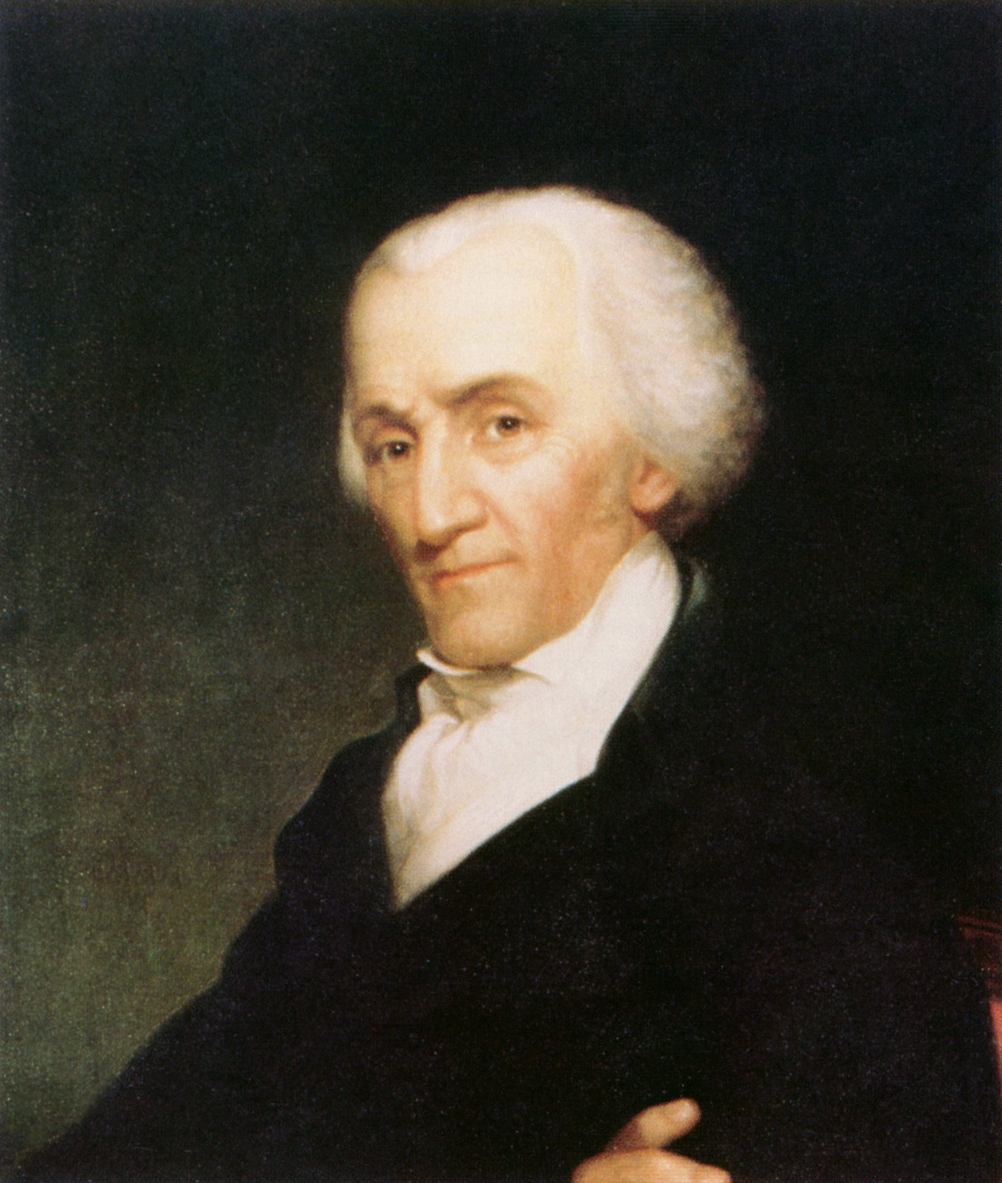

Elbridge Gerry (/ˈɡɛri/; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death in 1814.[1] The political practice of gerrymandering is named after him.[2]

This article is about the vice president of the United States. For other uses, see Elbridge Gerry (disambiguation).

Elbridge Gerry

Constituency established

July 17, 1744

Marblehead, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America

November 23, 1814 (aged 70)

Washington, District of Columbia, U.S.

10, including Thomas Russell Gerry

Harvard University (BA, MA)

Born into a wealthy merchant family, Gerry vocally opposed British colonial policy in the 1760s and was active in the early stages of organizing the resistance in the American Revolutionary War. Elected to the Second Continental Congress, Gerry signed both the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation.[3] He was one of three men who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, but refused to sign the Constitution because originally it did not include a Bill of Rights. After its ratification, he was elected to the inaugural United States Congress, where he was actively involved in the drafting and passage of the Bill of Rights as an advocate of individual and state liberties.

Gerry was at first opposed to the idea of political parties and cultivated enduring friendships on both sides of the political divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. He was a member of a diplomatic delegation to France that was treated poorly in the XYZ Affair, in which Federalists held him responsible for a breakdown in negotiations. Gerry thereafter became a Democratic-Republican, running unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts several times before winning the office in 1810. During his second term, the legislature approved new state senate districts that led to the coining of the word "gerrymander"; he lost the next election, although the state senate remained Democratic-Republican.

Gerry was nominated by the Democratic-Republican party and elected as vice president in the 1812 election. Advanced in age and in poor health, Gerry served 21 months of his term before dying in office. Gerry is the only signatory of the Declaration of Independence to be buried in Washington, D.C.

Early life and education[edit]

Gerry was born on July 17, 1744, in the North Shore town of Marblehead, Massachusetts. His father, Thomas Gerry (1702–1774), was a merchant who operated ships out of Marblehead, and his mother, Elizabeth (Greenleaf) Gerry (1716–1771), was the daughter of a successful Boston merchant.[4] Gerry's first name came from John Elbridge, one of his mother's ancestors.[5] Gerry's parents had 11 children in all, although only five survived to adulthood. Of these, Elbridge was the third.[6] He was first educated by private tutors and entered Harvard College shortly before turning 14. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1762 and a Master of Arts in 1765, he entered his father's merchant business. By the 1770s, the Gerrys numbered among the wealthiest Massachusetts merchants, with trading connections in Spain, the West Indies, and along the North American coast.[4][7] Gerry's father, who had emigrated from England in 1730, was active in local politics and had a leading role in the local militia.[8]

Colonial business and politics[edit]

Gerry was from an early time a vocal opponent of Parliamentary efforts to tax the colonies after the French and Indian War ended in 1763. In 1770, he sat on a Marblehead committee that sought to enforce importation bans on taxed British goods. He frequently communicated with other Massachusetts opponents of British policy, including Samuel Adams, John Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and others.[4]

In May 1772, he won election to the Great and General Court of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which served as the state's legislative assembly. He worked closely with Samuel Adams to advance colonial opposition to Parliamentary colonial policies. He was responsible for establishing Marblehead's committee of correspondence, one of the first to be set up after that of Boston.[9] However, an incident of mob action prompted him to resign from the committee the next year. Gerry and other prominent Marbleheaders had established a hospital for performing smallpox inoculations on Cat Island; because the means of transmission of the disease were not known at the time, fears amongst the local population led to protests which escalated into violence that wrecked the hospital and threatened the proprietors' other properties.[10]

Gerry reentered politics after the Boston Port Act closed that city's port in 1774, and Marblehead became an alternative port to which relief supplies from other colonies could be delivered. As one of the town's leading merchants and Patriots, Gerry played a major role in ensuring the storage and delivery of supplies from Marblehead to Boston, interrupting those activities only to care for his dying father. He was elected as a representative to the First Continental Congress in September 1774, but declined, still grieving the loss of his father.[11]

Gerry is generally remembered for the use of his name in the word gerrymander, for his refusal to sign the United States Constitution, and for his role in the XYZ Affair. His path through the politics of the age has been difficult to characterize. Early biographers, including his son-in-law James T. Austin and Samuel Eliot Morison, struggled to explain his apparent changes in position. Biographer George Athan Billias posits that Gerry was a consistent advocate and practitioner of republicanism as it was originally envisioned,[102] and that his role in the Constitutional Convention had a significant impact on the document it eventually produced.[103]

Gerry had ten children, nine of whom survived into adulthood:

Gerry's grandson Elbridge Thomas Gerry became a distinguished lawyer and philanthropist in New York. His great-grandson, Peter G. Gerry, was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and later a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island.[109]

Gerry is depicted in two of John Trumbull's paintings, the Declaration of Independence and General George Washington Resigning His Commission.[110] Both are on view in the rotunda of the United States Capitol.[111]

The upstate New York town of Elbridge is believed to have been named in his honor, as is the western New York town of Gerry.[112][113] The town of Phillipston, Massachusetts was originally incorporated in 1786 under the name Gerry in his honor but was changed to its present name after the town submitted a petition in 1812, citing Democratic-Republican support for the War of 1812.[114]

Gerry's Landing Road in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is located near the Eliot Bridge not far from Elmwood. During the 19th century, the area was known as Gerry's Landing (formerly known as Sir Richard's Landing) and was used by a Gerry relative for a short time as a landing and storehouse.[115][116] The supposed house of his birth, the Elbridge Gerry House (it is uncertain whether he was born in the house currently standing on the site or an earlier structure) stands in Marblehead, and Marblehead's Elbridge Gerry School is named in his honor.[117][118]

![General George Washington Resigning His Commission, a portrait by John Trumbull depicting Gerry standing on the left[111]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/General_George_Washington_Resigning_his_Commission.jpg/200px-General_George_Washington_Resigning_his_Commission.jpg)