Eleftherios Venizelos

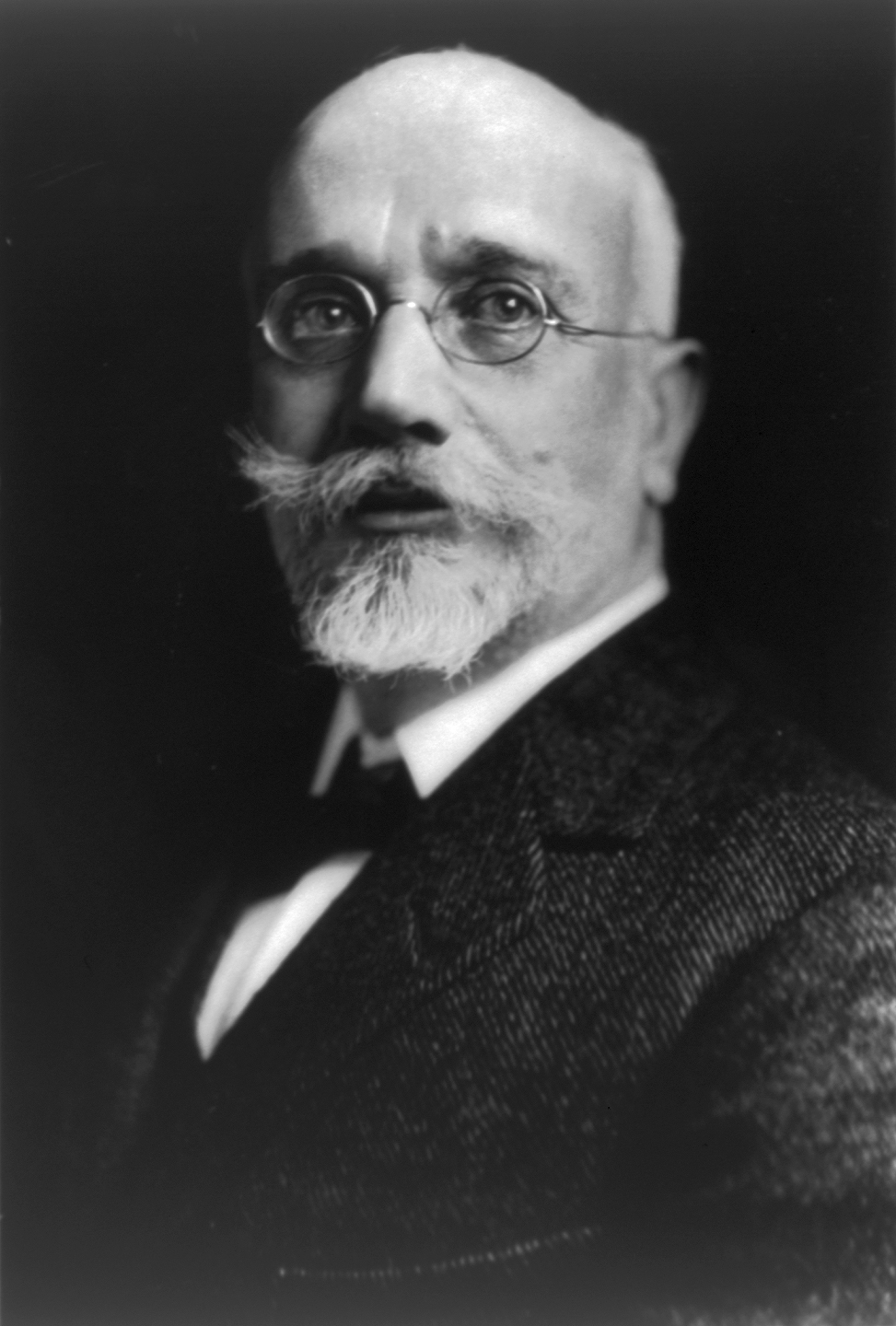

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (Greek: Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, romanized: Eleuthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, pronounced [elefˈθeri.os cirˈʝaku veniˈzelos]; 23 August [O.S. 11 August] 1864[1] – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. He is noted for his contribution to the expansion of Greece and promotion of liberal-democratic policies.[2][3][4] As leader of the Liberal Party, he held office as prime minister of Greece for over 12 years, spanning eight terms between 1910 and 1933. During his governance, Venizelos entered in diplomatic cooperation with the Great Powers and had profound influence on the internal and external affairs of Greece. He has therefore been labelled as "The Maker of Modern Greece"[5] and is still widely known as the "Ethnarch".[6]

For the Athens airport, see Athens International Airport.

Eleftherios Venizelos

Alexandros Zaimis (as High Commissioner)

Himself

Himself

23 August 1864

Mournies, Eyalet of Crete, Ottoman Empire (now Greece)

18 March 1936 (aged 71)

Paris, French Third Republic

Maria Katelouzou (1891–1894)

Helena Schilizzi (1921–1936)

Konstantinos Mitsotakis (nephew)

Kyriakos Mitsotakis (great-nephew)

Kyriakos Venizelos

Sophoklis Venizelos

Kyriakos Venizelos

Styliani Ploumidaki

![]() Order of the Redeemer

Order of the Redeemer![]() Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour![]() Order of the White Eagle

Order of the White Eagle

His first entry into the international scene was with his significant role in the autonomy of the Cretan State and later in the union of Crete with Greece. In 1909, he was invited to Athens to resolve the political deadlock and became the country's Prime Minister. He initiated constitutional and economic reforms that set the basis for the modernization of Greek society, and reorganized both the Greek Army and the Greek Navy in preparation of future conflicts.[7] Before the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, Venizelos' catalytic role helped gain Greece entrance to the Balkan League, an alliance of the Balkan states against the Ottoman Empire. Through his diplomatic acumen with the Great Powers and with the other Balkan countries, Greece doubled its area and population with the liberation of Macedonia, Epirus, and most of the Aegean islands.

In World War I (1914–1918), he brought Greece on the side of the Allies, further expanding the Greek borders. However, his pro-Allied foreign policy brought him into conflict with the nonaligned faction of Constantine I of Greece, causing the National Schism of the 1910s. The Schism became an unofficial civil war, with the struggle for power between the two groups polarizing the population between the royalists and Venizelists for decades.[8][9] Following the Allied victory, Venizelos secured new territorial concessions in Western Anatolia and Thrace in an attempt to accomplish the Megali Idea, which would have united all Greek-speaking people along the Aegean Sea under the banner of Greece. He was however defeated in the 1920 General Election, which contributed to the eventual Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22). Venizelos, in self-imposed exile, represented Greece in the negotiations that led to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne and the agreement of a mutual population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

In his subsequent periods in office, Venizelos restored normal relations with Greece's neighbors and expanded his constitutional and economic reforms. In 1935, he resurfaced from retirement to support a military coup. The coup's failure severely weakened the Second Hellenic Republic.

Death[edit]

Venizelos left for Paris and on 12 March 1936 wrote his last letter to Alexandros Zannas. He suffered a stroke on the morning of the 13th and died five days later in his flat at 22 rue Beaujon.[116] The absolution was performed on 21 March at St. Stephen's Greek Orthodox Church; his body was deposed in the crypt before its transportation on the 23rd at the beginning of the afternoon to the Gare de Lyon. His body was then taken by the destroyer Pavlos Kountouriotis to Chania, avoiding Athens in order not to cause unrest. A great ceremony with wide public attendance accompanied his burial at Akrotiri, Crete.

Personal life and family[edit]

In December 1891, Venizelos married Maria Katelouzou, daughter of Eleftherios Katelouzos. The newlyweds lived on the upper floor of the Chalepa house, while Venizelos' mother and his brother and sisters lived on the ground floor. There, they enjoyed the happy moments of their marriage and also had the birth of their two children, Kyriakos in 1892 and Sofoklis in 1894. Their married life was short and marked by misfortune. Maria died of post-puerperal fever in November 1894 after the birth of their second child. Her death deeply affected Venizelos and as a sign of mourning, he grew his characteristic beard and mustache, which he retained for the rest of his life.[12]

After his defeat in the November elections of 1920, he left for Nice and Paris in self-imposed exile. In September 1921, twenty-seven years after the death of his first wife Maria, he married Helena Schilizzi (sometimes referred to as Elena Skylitsi or Stephanovich) in London. Advised by police to be wary of assassination attempts, they held the religious ceremony in private at Witanhurst, the mansion of a family friend and socialite Lady Domini Crosfield. The Crosfields were well connected and Venizelos met Arthur Balfour, David Lloyd George and the arms dealer Basil Zaharoff in subsequent visits to the house.

The married couple settled down in Paris in a flat at 22 rue Beaujon. He lived there until 1927 when he returned to Chania.[12]