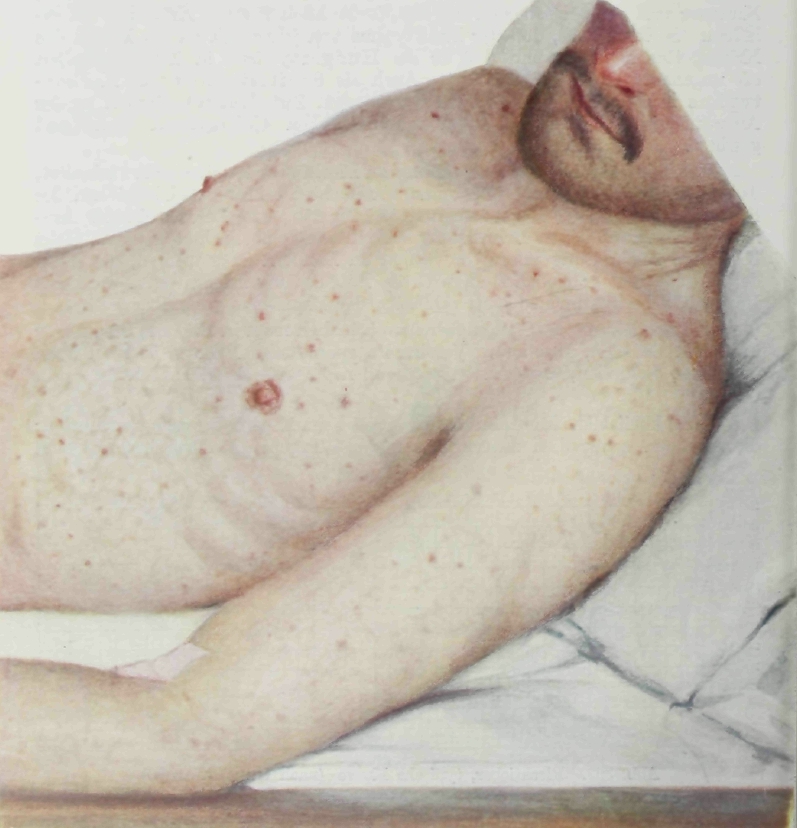

Epidemic typhus

Epidemic typhus, also known as louse-borne typhus, is a form of typhus so named because the disease often causes epidemics following wars and natural disasters where civil life is disrupted.[4][5] Epidemic typhus is spread to people through contact with infected body lice, in contrast to endemic typhus which is usually transmitted by fleas.[4][5]

Typhus

Though typhus has been responsible for millions of deaths throughout history, it is still considered a rare disease that occurs mainly in populations that suffer unhygienic extreme overcrowding.[6] Typhus is most rare in industrialized countries. It occurs primarily in the colder, mountainous regions of central and east Africa, as well as Central and South America.[7] The causative organism is Rickettsia prowazekii, transmitted by the human body louse (Pediculus humanus corporis).[8][9] Untreated typhus cases have a fatality rate of approximately 40%.[7]

Epidemic typhus should not be confused with murine typhus, which is more endemic to the United States, particularly Southern California and Texas. This form of typhus has similar symptoms but is caused by Rickettsia typhi, is less deadly, and has different vectors for transmission.[10]

Treatment[edit]

The infection is treated with antibiotics. Intravenous fluids and oxygen may be needed to stabilize the patient. There is a significant disparity between the untreated mortality and treated mortality rates: 10-60% untreated versus close to 0% treated with antibiotics within 8 days of initial infection. Tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and doxycycline[14] are commonly used.

Some of the simplest methods of prevention and treatment focus on preventing infestation of body lice. Completely changing the clothing, washing the infested clothing in hot water, and in some cases also treating recently used bedsheets all help to prevent typhus by removing potentially infected lice. Clothes left unworn and unwashed for 7 days also result in the death of both lice and their eggs, as they have no access to a human host.[15] Another form of lice prevention requires dusting infested clothing with a powder consisting of 10% DDT, 1% malathion, or 1% permethrin, which kill lice and their eggs.[14]

Other preventive measures for individuals are to avoid unhygienic, extremely overcrowded areas where the causative organisms can jump from person to person. In addition, they are warned to keep a distance from larger rodents that carry lice, such as rats, squirrels, or opossums.[14]

Society and culture[edit]

Biological weapon[edit]

Typhus was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before President Richard Nixon suspended all non-defensive aspects of the U.S. biological weapons program in 1969.[38]

Poverty and displacement[edit]

The CDC lists the following areas as active foci of human epidemic typhus: Andean regions of South America, some parts of Africa; on the other hand, the CDC only recognizes an active enzootic cycle in the United States involving flying squirrels (CDC). Though epidemic typhus is commonly thought to be restricted to areas of the developing world, serological examination of homeless persons in Houston found evidence for exposure to the bacterial pathogens that cause epidemic typhus and murine typhus. A study involving 930 homeless people in Marseille, France, found high rates of seroprevalence to R. prowazekii and a high prevalence of louse-borne infections in the homeless.

Typhus has been increasingly discovered in homeless populations in developed nations. Typhus among homeless populations is especially prevalent as these populations tend to migrate across states and countries, spreading the risk of infection with their movement. The same risk applies to refugees, who travel across country lines, often living in close proximity and unable to maintain necessary hygienic standards to avoid being at risk for catching lice possibly infected with typhus.

Because the typhus-infected lice live in clothing, the prevalence of typhus is also affected by weather, humidity, poverty and lack of hygiene. Lice, and therefore typhus, are more prevalent during colder months, especially winter and early spring. In these seasons, people tend to wear multiple layers of clothing, giving lice more places to go unnoticed by their hosts. This is particularly a problem for poverty-stricken populations as they often do not have multiple sets of clothing, preventing them from practicing good hygiene habits that could prevent louse infestation.[15]

Due to fear of an outbreak of epidemic typhus, the US Government put a typhus quarantine in place in 1917 across the entirety of the US-Mexican border. Sanitation plants were constructed that required immigrants to be thoroughly inspected and bathed before crossing the border. Those who routinely crossed back and forth across the border for work were required to go through the sanitation process weekly, updating their quarantine card with the date of the next week's sanitation. These sanitation border stations remained active over the next two decades, regardless of the disappearance of the typhus threat. This fear of typhus and resulting quarantine and sanitation protocols dramatically hardened the border between the US and Mexico, fostering scientific and popular prejudices against Mexicans. This ultimately intensified racial tensions and fueled efforts to ban immigrants to the US from the Southern Hemisphere because the immigrants were associated with the disease.[39]