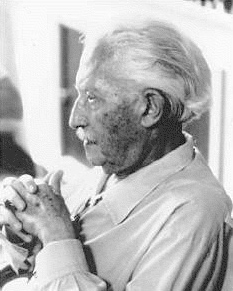

Erik Erikson

Erik Homburger Erikson (born Erik Salomonsen; 15 June 1902 – 12 May 1994) was an American child psychoanalyst known for his theory on psychosocial development of human beings. He coined the phrase identity crisis.

For other people with similar names, see Eric Erickson (disambiguation).

Erik Erikson

12 May 1994 (aged 91)

- American

- German

4, including Kai T. Erikson

- Pulitzer Prize (1970)

- National Book Award (1970)

Psychology

- Childhood and Society (1950)

- Young Man Luther (1958)

- Gandhi's Truth (1969)

- The Life Cycle Completed (1987)

Despite lacking a university degree, Erikson served as a professor at prominent institutions, including Harvard, University of California, Berkeley,[9] and Yale. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Erikson as the 12th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[10]

Early life[edit]

Erikson's mother, Karla Abrahamsen, came from a prominent Jewish family in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was married to Jewish stockbroker Valdemar Isidor Salomonsen, but had been estranged from him for several months at the time Erik was conceived. Little is known about Erik's biological father except that he was a non-Jewish Dane. On discovering her pregnancy, Karla fled to Frankfurt am Main in Germany where Erik was born on 15 June 1902 and was given the surname Salomonsen.[11] She fled due to conceiving Erik out of wedlock, and the identity of Erik's birth father was never made clear.[9]

Following Erik's birth, Karla trained to be a nurse and moved to Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1905 she married a Jewish pediatrician, Theodor Homburger. In 1908, Erik Salomonsen's name was changed to Erik Homburger, and in 1911 he was officially adopted by his stepfather.[12] Karla and Theodor told Erik that Theodor was his real father, only revealing the truth to him in late childhood; he remained bitter about the deception all his life.[9]

The development of identity seems to have been one of Erikson's greatest concerns in his own life as well as being central to his theoretical work. As an older adult, he wrote about his adolescent "identity confusion" in his European days. "My identity confusion", he wrote "[was at times on] the borderline between neurosis and adolescent psychosis." Erikson's daughter wrote that her father's "real psychoanalytic identity" was not established until he "replaced his stepfather's surname [Homburger] with a name of his own invention [Erikson]."[13] The decision to change his last name came about as he started his job at Yale, and the "Erikson" name was accepted by Erik's family when they became American citizens.[9] It is said his children enjoyed the fact they would not be called "Hamburger" any longer.[9]

Erik was a tall, blond, blue-eyed boy who was raised in the Jewish religion. Due to these mixed identities, he was a target of bigotry by both Jewish and gentile children. At temple school, his peers teased him for being Nordic; while at grammar school, he was teased for being Jewish.[14] At Das Humanistische Gymnasium his main interests were art, history and languages, but he lacked a general interest in school and graduated without academic distinction.[15] After graduation, instead of attending medical school as his stepfather had desired, he attended art school in Munich, much to the liking of his mother and her friends.

Uncertain about his vocation and his fit in society, Erik dropped out of school and began a lengthy period of roaming about Germany and Italy as a wandering artist with his childhood friend Peter Blos and others. For children from prominent German families, taking a "wandering year" was not uncommon. During his travels he often sold or traded his sketches to people he met. Eventually, Erik realized he would never become a full-time artist and returned to Karlsruhe and became an art teacher. During the time he worked at his teaching job, Erik was hired by an heiress to sketch and eventually tutor her children. Erik worked very well with these children and was eventually hired by many other families that were close to Anna and Sigmund Freud.[9] During this period, which lasted until he was twenty-five years old, he continued to contend with questions about his father and competing ideas of ethnic, religious, and national identity.[16]

Psychoanalytic experience and training[edit]

When Erikson was twenty-five, his friend Peter Blos invited him to Vienna to tutor art[9] at the small Burlingham-Rosenfeld School for children whose affluent parents were undergoing psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud's daughter, Anna Freud.[17] Anna noticed Erikson's sensitivity to children at the school and encouraged him to study psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute, where prominent analysts August Aichhorn, Heinz Hartmann, and Paul Federn were among those who supervised his theoretical studies. He specialized in child analysis and underwent a training analysis with Anna Freud. Helene Deutsch and Edward Bibring supervised his initial treatment of an adult.[17] Simultaneously he studied the Montessori method of education, which focused on child development and sexual stages.[18] In 1933 he received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. This and his Montessori diploma were to be Erikson's only earned credentials for his life's work.

United States[edit]

In 1930 Erikson married Joan Mowat Serson, a Canadian dancer and artist whom Erikson had met at a dress ball.[8][19][20] During their marriage, Erikson converted to Christianity.[21][22] In 1933, with Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, the burning of Freud's books in Berlin and the potential Nazi threat to Austria, the family left an impoverished Vienna with their two young sons and emigrated to Copenhagen.[23] Unable to regain Danish citizenship because of residence requirements, the family left for the United States, where citizenship would not be an issue.[24]

In the United States, Erikson became the first child psychoanalyst in Boston and held positions at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Judge Baker Guidance Center, and at Harvard Medical School and Psychological Clinic. This was while he was establishing a singular reputation as a clinician. In 1936, Erikson left Harvard and joined the staff at Yale University, where he worked at the Institute of Social Relations and taught at the medical school.[25]

Erikson continued to deepen his interest in areas beyond psychoanalysis and to explore connections between psychology and anthropology. He made important contacts with anthropologists such as Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Ruth Benedict.[26] Erikson said his theory of the development of thought derived from his social and cultural studies. In 1938, he left Yale to study the Sioux tribe in South Dakota on their reservation. After his studies in South Dakota, he traveled to California to study the Yurok tribe. Erikson discovered differences between the children of the Sioux and Yurok tribes. This marked the beginning of Erikson's life passion of showing the importance of events in childhood and how society affects them.[27]

In 1939 he left Yale, and the Eriksons moved to California, where Erik had been invited to join a team engaged in a longitudinal study of child development for the University of California at Berkeley's Institute of Child Welfare. In addition, in San Francisco, he opened a private practice in child psychoanalysis.

While in California he was able to make his second study of American Indian children when he joined anthropologist Alfred Kroeber on a field trip to Northern California to study the Yurok.[15]

In 1950, after publishing the book, Childhood and Society, for which he is best known, Erikson left the University of California when California's Levering Act required professors there to sign loyalty oaths.[28] From 1951 to 1960 he worked and taught at the Austen Riggs Center, a prominent psychiatric treatment facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he worked with emotionally troubled young people. Another famous Stockbridge resident, Norman Rockwell, became Erikson's patient and friend. During this time he also served as a visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh where he worked with Benjamin Spock and Fred Rogers at Arsenal Nursery School of the Western Psychiatric Institute.[29]

He returned to Harvard in the 1960s as a professor of human development and remained there until his retirement in 1970.[30] In 1973 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Erikson for the Jefferson Lecture, the United States' highest honor for achievement in the humanities. Erikson's lecture was titled Dimensions of a New Identity.[31][32]

Theories of development and the ego[edit]

Erikson is credited with being one of the originators of ego psychology, which emphasized the role of the ego as being more than a servant of the id. Although Erikson accepted Freud's theory, he did not focus on the parent-child relationship and gave more importance to the role of the ego, particularly the person's progression as self.[33] According to Erikson, the environment in which a child lived was crucial to providing growth, adjustment, a source of self-awareness and identity. Erikson won a Pulitzer Prize[34] and a US National Book Award in category Philosophy and Religion[35] for Gandhi's Truth (1969),[36] which focused more on his theory as applied to later phases in the life cycle.

In Erikson's discussion of development, he rarely mentioned a stage of development by age. In fact he referred to it as a prolonged adolescence which has led to further investigation into a period of development between adolescence and young adulthood called emerging adulthood.[37] Erikson's theory of development includes various psychosocial crises where each conflict builds off of the previous stages.[38] The result of each conflict can have negative or positive impacts on a person's development, however, a negative outcome can be revisited and readdressed throughout the life span.[39] On ego identity versus role confusion: ego identity enables each person to have a sense of individuality, or as Erikson would say, "Ego identity, then, in its subjective aspect, is the awareness of the fact that there is a self-sameness and continuity to the ego's synthesizing methods and a continuity of one's meaning for others".[40] Role confusion, however, is, according to Barbara Engler, "the inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member of one's own society."[41] This inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member is a great danger; it can occur during adolescence, when looking for an occupation.

Psychology of religion[edit]

Psychoanalytic writers have always engaged in nonclinical interpretation of cultural phenomena such as art, religion, and historical movements. Erik Erikson gave such a strong contribution that his work was well received by students of religion and spurred various secondary literature.[58]

Erikson's psychology of religion begins with an acknowledgement of how religious tradition can have an interplay with a child's basic sense of trust or mistrust.[59] With regard to Erikson's theory of personality as expressed in his eight stages of the life cycle, each with their different tasks to master, each also included a corresponding virtue, as mentioned above, which form a taxonomy for religious and ethical life. Erikson extends this construct by emphasizing that human individual and social life is characterized by ritualization, "an agreed-upon interplay between at least two persons who repeat it at meaningful intervals and in recurring contexts." Such ritualization involves careful attentiveness to what can be called ceremonial forms and details, higher symbolic meanings, active engagement of participants, and a feeling of absolute necessity.[60] Each life cycle stage includes its own ritualization with a corresponding ritualism: numinous vs. idolism, judicious vs. legalism, dramatic vs. impersonation, formal vs. formalism, ideological vs. totalism, affiliative vs. elitism, generational vs. authoritism, and integral vs. dogmatism.[61]

Perhaps Erikson's best-known contributions to the psychology of religion were his book length psychobiographies, Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History, on Martin Luther, and Gandhi's Truth, on Mohandas K. Gandhi, for which he remarkably won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Both books attempt to show how childhood development and parental influence, social and cultural context, even political crises form a confluence with personal identity. These studies demonstrate how each influential person discovered mastery, both individually and socially, in what Erikson would call the historical moment. Individuals like Luther or Gandhi were what Erikson called a Homo Religiosus, individuals for whom the final life cycle challenge of integrity vs. despair is a lifelong crisis, and they become gifted innovators whose own psychological cure becomes an ideological breakthrough for their time.[58]

Personal life[edit]

Erikson married Canadian-born American dancer and artist Joan Erikson (née Sarah Lucretia Serson) in 1930 and they remained together until his death.[21]

The Eriksons had four children: Kai T. Erikson, Jon Erikson, Sue Erikson Bloland, and Neil Erikson. His eldest son, Kai T. Erikson, is an American sociologist. Their daughter, Sue, "an integrative psychotherapist and psychoanalyst",[62] described her father as plagued by "lifelong feelings of personal inadequacy".[63] He thought that by combining resources with his wife, he could "achieve the recognition" that might produce a feeling of adequacy.[64]

Erikson died on 12 May 1994 in Harwich, Massachusetts. He is buried in the First Congregational Church Cemetery in Harwich.[65]