Problem of evil

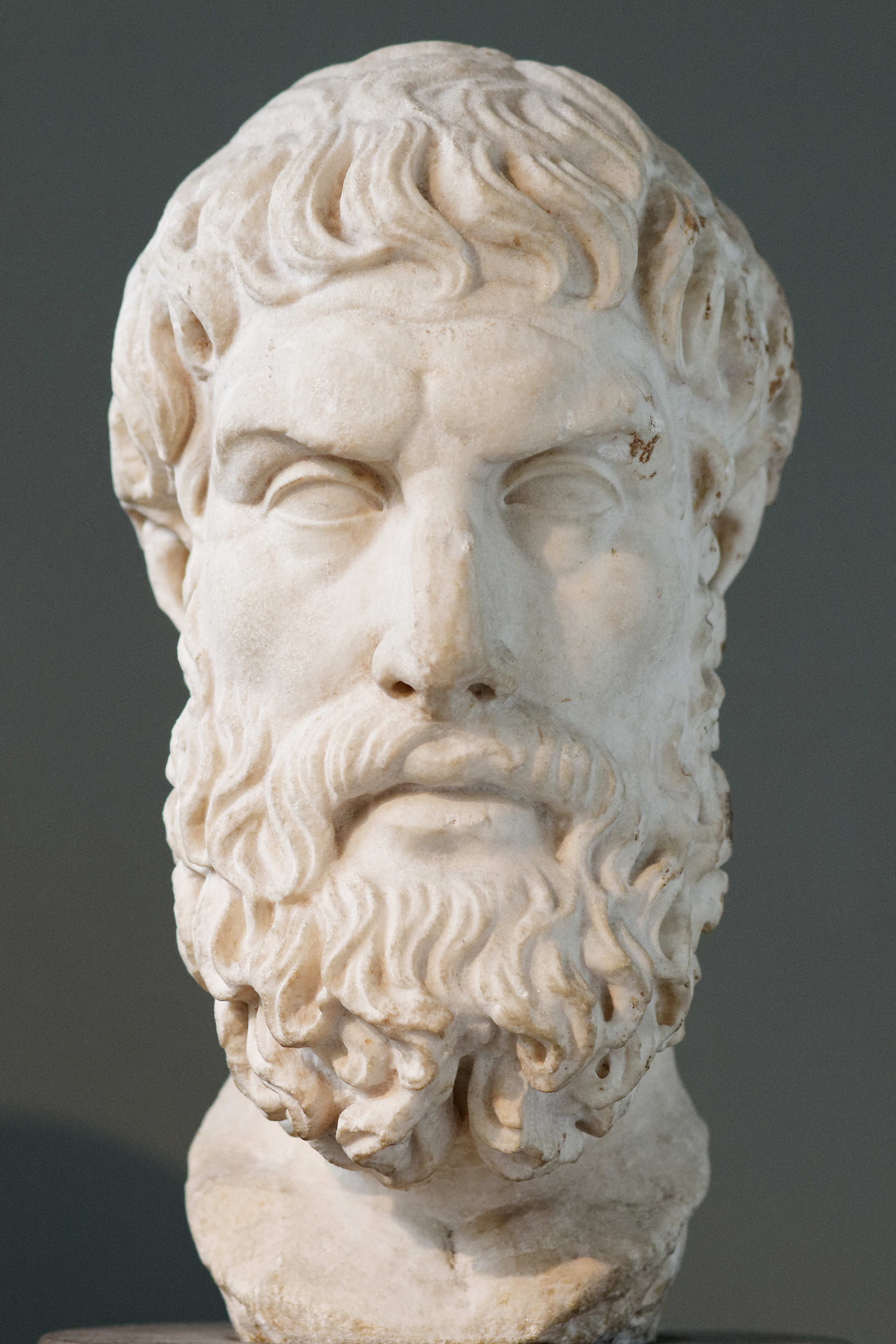

The problem of evil is the philosophical question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.[1][2][3] There are currently differing definitions of these concepts. The best known presentation of the problem is attributed to the Greek philosopher Epicurus. It was popularized by David Hume.

Besides the philosophy of religion, the problem of evil is also important to the fields of theology and ethics. There are also many discussions of evil and associated problems in other philosophical fields, such as secular ethics,[4][5][6] and evolutionary ethics.[7][8] But as usually understood, the problem of evil is posed in a theological context.[2][3]

Responses to the problem of evil have traditionally been in three types: refutations, defenses, and theodicies.

The problem of evil is generally formulated in two forms: the logical problem of evil and the evidential problem of evil. The logical form of the argument tries to show a logical impossibility in the coexistence of a god and evil,[2][9] while the evidential form tries to show that given the evil in the world, it is improbable that there is an omnipotent, omniscient, and a wholly good god.[3] The problem of evil has been extended to non-human life forms, to include suffering of non-human animal species from natural evils and human cruelty against them.[10]

Definitions[edit]

Evil[edit]

A broad concept of evil defines it as any and all pain and suffering,[11] yet this definition quickly becomes problematic. Marcus Singer says that a usable definition of evil must be based on the knowledge that: "If something is really evil, it can't be necessary, and if it is really necessary, it can't be evil".[12]: 186 According to John Kemp, evil cannot be correctly understood on "a simple hedonic scale on which pleasure appears as a plus, and pain as a minus".[13][11] The National Institute of Medicine says pain is essential for survival: "Without pain, the world would be an impossibly dangerous place".[14][15]

While many of the arguments against an omni-God are based on the broadest definition of evil, "most contemporary philosophers interested in the nature of evil are primarily concerned with evil in a narrower sense".[16] The narrow concept of evil involves moral condemnation, and is applicable only to moral agents capable of making independent decisions, and their actions; it allows for the existence of some pain and suffering without identifying it as evil.[17]: 322 Christianity is based on "the salvific value of suffering".[18]

Philosopher Eve Garrard suggests that the term evil cannot be used to describe ordinary wrongdoing, because "there is a qualitative and not merely a quantitative difference between evil acts and other wrongful ones; evil acts are not just very bad or wrongful acts, but rather ones possessing some specially horrific quality".[17]: 321 Calder argues that evil must involve the attempt or desire to inflict significant harm on the victim without moral justification.[11]

Evil takes on different meanings when seen from the perspective of different belief systems, and while evil can be viewed in religious terms, it can also be understood in natural or secular terms, such as social vice, egoism, criminality, and sociopathology.[19] John Kekes writes that an action is evil if "(1) it causes grievous harm to (2) innocent victims, and it is (3) deliberate, (4) malevolently motivated, and (5) morally unjustifiable".[20]

Omni-qualities[edit]

Omniscience is "maximal knowledge".[21] According to Edward Wierenga, a classics scholar and doctor of philosophy and religion at the University of Massachusetts, maximal is not unlimited but limited to "God knowing what is knowable".[22]: 25 This is the most widely accepted view of omniscience among scholars of the twenty-first century, and is what William Hasker calls freewill-theism. Within this view, future events that depend upon choices made by individuals with free will are unknowable until they occur.[23]: 104, 137 [21]: 18–20

Omnipotence is maximal power to bring about events within the limits of possibility, but again maximal is not unlimited.[24] According to the philosophers Hoffman and Rosenkrantz: "An omnipotent agent is not required to bring about an impossible state of affairs... maximal power has logical and temporal limitations, including the limitation that an omnipotent agent cannot bring about, i.e., cause, another agent's free decision".[24]

Omnibenevolence sees God as all-loving. If God is omnibenevolent, he acts according to what is best, but if there is no best available, God attempts, if possible, to bring about states of affairs that are creatable and are optimal within the limitations of physical reality.[25]

Defenses and theodicies[edit]

Responses to the problem of evil have occasionally been classified as defences or theodicies although authors disagree on the exact definitions.[2][3][26] Generally, a defense refers to attempts to address the logical argument of evil that says "it is logically impossible – not just unlikely – that God exists".[3] A defense does not require a full explanation of evil, and it need not be true, or even probable; it need only be possible, since possibility invalidates the logic of impossibility.[27][9]

A theodicy, on the other hand, is more ambitious, since it attempts to provide a plausible justification – a morally or philosophically sufficient reason – for the existence of evil. This is intended to weaken the evidential argument which uses the reality of evil to argue that the existence of God is unlikely.[3][28]

Secularism[edit]

In philosopher Forrest E. Baird's view, one can have a secular problem of evil whenever humans seek to explain why evil exists and its relationship to the world.[29] He adds that any experience that "calls into question our basic trust in the order and structure of our world" can be seen as evil,[29] therefore, according to Peter L. Berger, humans need explanations of evil "for social structures to stay themselves against chaotic forces".[30]