Faraday's law of induction

Faraday's law of induction (or simply Faraday's law) is a law of electromagnetism predicting how a magnetic field will interact with an electric circuit to produce an electromotive force (emf). This phenomenon, known as electromagnetic induction, is the fundamental operating principle of transformers, inductors, and many types of electric motors, generators and solenoids.[2][3]

The Maxwell–Faraday equation (listed as one of Maxwell's equations) describes the fact that a spatially varying (and also possibly time-varying, depending on how a magnetic field varies in time) electric field always accompanies a time-varying magnetic field, while Faraday's law states that there is emf (electromotive force, defined as electromagnetic work done on a unit charge when it has traveled one round of a conductive loop) on a conductive loop when the magnetic flux through the surface enclosed by the loop varies in time.

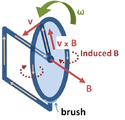

Faraday's law had been discovered and one aspect of it (transformer emf) was formulated as the Maxwell–Faraday equation later. The equation of Faraday's law can be derived by the Maxwell–Faraday equation (describing transformer emf) and the Lorentz force (describing motional emf). The integral form of the Maxwell–Faraday equation describes only the transformer emf, while the equation of Faraday's law describes both the transformer emf and the motional emf.

It is tempting to generalize Faraday's law to state: If ∂Σ is any arbitrary closed loop in space whatsoever, then the total time derivative of magnetic flux through Σ equals the emf around ∂Σ. This statement, however, is not always true and the reason is not just from the obvious reason that emf is undefined in empty space when no conductor is present. As noted in the previous section, Faraday's law is not guaranteed to work unless the velocity of the abstract curve ∂Σ matches the actual velocity of the material conducting the electricity.[31] The two examples illustrated below show that one often obtains incorrect results when the motion of ∂Σ is divorced from the motion of the material.[18]

One can analyze examples like these by taking care that the path ∂Σ moves with the same velocity as the material.[31] Alternatively, one can always correctly calculate the emf by combining Lorentz force law with the Maxwell–Faraday equation:[18]: ch17 [32]

where "it is very important to notice that (1) [vm] is the velocity of the conductor ... not the velocity of the path element dl and (2) in general, the partial derivative with respect to time cannot be moved outside the integral since the area is a function of time."[32]