Fritz the Cat (film)

Fritz the Cat is a 1972 American adult animated black comedy film written and directed by Ralph Bakshi in his directorial debut. Based on the comic strip of the same name by Robert Crumb, the film focuses on its Skip Hinnant-portrayed titular character, a glib, womanizing and fraudulent cat in an anthropomorphic animal version of New York City during the mid-to-late 1960s. Fritz decides on a whim to drop out of college, interacts with inner city African American crows, unintentionally starts a race riot and becomes a leftist revolutionary. The film is a satire focusing on American college life of the era, race relations and the free love movement, as well as serving as a criticism of the countercultural political revolution and dishonest political activists.

Fritz the Cat

Ralph Bakshi

- Skip Hinnant

- Rosetta LeNoire

- John McCurry

- Judy Engles

- Phil Seuling

- Ted Bemiller

- Gene Borghi

Renn Reynolds

- Manny Perez

- Art Vitello

- Phil Duncan

- Dick Lundy

- Virgil Ross

- Norm McCabe

- John Sparey

- George Griffin[1][2]

- James Tyer

- John Gentilella

- Rod Scribner

- Ted Bonnicksen

- Fritz Productions

- Aurica Finance Company

- Krantz Films

- April 12, 1972

78 minutes[3]

United States

- English

- Yiddish

$700,000

$90 million

The film had a troubled production history, as Crumb, who is a leftist, had disagreements with the filmmakers over the film's political content, which he saw as being critical of the political left.[4][5][6] Produced on a budget of $700,000,[7] the film was intended by Bakshi to broaden the animation market. At that time, animation was seen predominantly as a children's medium. Bakshi envisioned animation as a medium that could tell more dramatic or satirical storylines with larger scopes, dealing with more mature and diverse themes that would resonate with adults. Bakshi also wanted to establish an independent alternative to the films produced by Walt Disney Productions, which dominated the animation market due to a lack of independent competition.

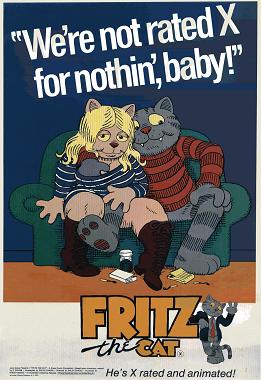

The film's depiction of profanity, sex and drug use, particularly cannabis, provoked criticism from more conservative members of the animation industry, who accused Bakshi of attempting to produce a pornographic animated film, as the concept of adult animation was not widely understood at the time. The Motion Picture Association of America gave the film an X rating (the predecessor of the NC-17 rating), making it the first American animated film to receive the rating, which was then predominantly associated with more arthouse films.

The film was highly successful, grossing over $90 million worldwide, making it one of the most successful independent films of all time.[8] It earned significant critical acclaim in the 1970s, for its satire, social commentary and animations, although it also attracted some negative response accusing it of racial stereotyping and having an unfocused plot, and criticizing its depiction of graphic violence, profanity, sex and drug use in the context of an animated film. The film's use of satire and mature themes is seen as paving the way for future animated works for adults, including The Simpsons,[9] South Park,[9][10] Beavis and Butt-Head, and Family Guy.

A sequel, The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat (1974), was produced without Crumb's or Bakshi's involvement.

Plot[edit]

In the 1960s, at Washington Square Park in Manhattan, hippies gather to perform protest songs. Fritz, a tabby cat, and his friends show up in an attempt to meet girls. When a trio of attractive girls walk by, Fritz and his friends exhaust themselves trying to get their attention with their music, but are annoyed to find that the girls are more interested in the crow standing nearby. The girls attempt to flirt with the crow, making unintentionally condescending remarks about black people. After the crow snidely rebukes the girls and leaves, Fritz convinces the girls that he is a suffering soul and invites them to "seek the truth".

The group arrive at his friend's apartment, where a wild party is taking place. Since the other rooms are crowded, Fritz drags the girls into the bathroom and the four of them have an orgy in the bathtub. Meanwhile, two pig police officers from the NYPD arrive to close down the party. As they walk up the stairs, one of the partygoers finds Fritz and the girls in the bath tub. Several others jump in, pushing Fritz to the side, where he takes solace in marijuana. The two officers break into the apartment, but find that it is empty because everyone has moved into the bathroom. Fritz takes refuge in the toilet when one of the officers enters the bathroom and begins to beat up the partygoers. As the officer becomes exhausted, a stoned Fritz jumps out, grabs the officer's gun, and shoots the toilet, causing the water main to break and flooding everybody out of the apartment. The pigs chase Fritz down the street into a synagogue. Fritz manages to escape when the congregation gets up to celebrate the United States' decision to ship more weapons to Israel.

Fritz makes it back to his dormitory, where his roommates are too busy studying to pay attention to him. He decides to ditch his bore of a life and sets all of his notes and books on fire. The fire spreads throughout the dorm, finally setting the entire building ablaze. In a bar in Harlem, Fritz meets Duke the Crow at a pool table. After narrowly avoiding getting into a fight with the bartender, Duke invites Fritz to "bug out", and they steal a car, which Fritz drives off a bridge, leading Duke to save his life by grabbing onto a railing. The two arrive at the apartment of a drug dealer named Bertha, whose cannabis joints increase Fritz's libido. While fornicating with Bertha, he realizes that he "must tell the people about the revolution". He runs off into the city street and incites a riot, during which Duke is shot and killed by one of the police officers. The situation escalates into absolute chaos as both the police and the New York Air National Guard is sent to New York in order to quell the riots. The violence ends as 3 F-104 jets Carpet bombing the entirety of Harlem.

Fritz hides in an alley, where his older fox girlfriend, Winston Schwartz, finds him and drags him on a road trip to San Francisco. When their car runs out of gas in the middle of the desert, he decides to abandon her. He later meets up with Blue, a drug-addicted rabbit biker. Along with Blue's horse girlfriend, Harriet, they take a ride to an underground hide-out, where two other revolutionaries— an unnamed female gecko that is only known as "the lizard leader" and John, a hooded snake—tell Fritz of their plan to blow up a power station. When Harriet tries to get Blue to leave with her to go to a Chinese restaurant, he hits her several times and ties her down with a chain. When Fritz attempts to break it up, the leader throws a candle in his face. Blue, John, and the lizard leader then throw Harriet onto a bed to gang rape her. After setting the dynamite at the power plant, Fritz suddenly has a change of heart and unsuccessfully attempts to remove it before being caught in the explosion.

At a Los Angeles hospital, Harriet, disguised as a nun, and the girls from the New York park come to comfort him in what they believe to be his last moments. Fritz, after reciting the speech he used to pick up the girls from New York, suddenly becomes revitalized and has a foursome with the trio of girls while Harriet watches in astonishment, and the movie ends with a deputy from the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department stationed in the hospital saying: "Eh, poor cat. He was a - he was a kind a tough kid at that, wasn't he?".

Production[edit]

Funding and distribution[edit]

With the rights to the character, Krantz and Bakshi set out to find a distributor, but Krantz states that "every major distributor turned it down"[5] and that studios were unenthusiastic about producing an independent animated film due to the prominence of Walt Disney Productions in animation, in addition to the fact that Fritz the Cat would be a very different animated film from what had previously been made.[17]

In the spring of 1970, Warner Bros. agreed to fund and distribute the film.[18][24] The Harlem sequences were the first to be completed. Krantz intended to release these scenes as a 15-minute short if the film's funding was pulled; Bakshi was nevertheless determined to complete the film as a feature.[23] Late in November, Bakshi and Krantz screened a presentation reel for the studio with this sequence, pencil tests, and shots of Bakshi's storyboards.[25] Bakshi stated, "You should have seen their faces in the screening room when I first screened a bit of Fritz. I'll remember their faces until I die. One of them left the room. Holy hell, you should have seen his face. 'Shut up, Frank! This is not the movie you're allowed to make!' And I said, Bullshit, I just made it."[26]

The film's budget is disputed. In 1972, The Hollywood Reporter stated that Fritz the Cat recouped its costs in four months following its release. A year later the magazine reported that the film grossed $30 million worldwide and was produced on a budget of $1.3 million. In 1993, director Ralph Bakshi said "Fritz the Cat, to me, was an enormous budget – at $850,000 – compared to my Terrytoon budgets." In an interview published in 1980, Bakshi stated "We made the film for $700,000. Complete".[7]

Warner executives wanted the sexual content toned down and to cast big names for the voices. Bakshi refused, and Warner pulled their funding from the film, leading Krantz to seek funds elsewhere. This led to a deal with Jerry Gross, the owner of Cinemation Industries, a distributor specializing in exploitation films. Although Bakshi did not have enough time to pitch the film, Gross agreed to fund its production and distribute it, believing that it would fit in with his grindhouse slate.[23] Further financing came from Saul Zaentz, who agreed to distribute the soundtrack album on his Fantasy Records label.[23]

Rating[edit]

Fritz received an X rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (equivalent to the modern NC-17 rating), becoming the first American animated film to receive such a rating. However, at the time, the rating was associated with more arthouse fare, and since the recently released Melvin Van Peebles film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, which was released through Cinemation, had received both an X rating and considerable success, the distributor hoped that Fritz the Cat would be even more profitable.[49] Producer Krantz stated that the film lost playdates due to the rating, and 30 American newspapers rejected display advertisements for it or refused to give it editorial publicity.[18] The film's limited screenings led Cinemation to exploit the film's content in its promotion of the film, advertising it as containing "90 minutes of violence, excitement, and SEX ... he's X-rated and animated!"[49] According to Ralph Bakshi, "We almost didn't deliver the picture, because of the exploitation of it."[17]

Cinemation's advertising style and the film's rating led many to believe that Fritz the Cat was a pornographic film. When it was introduced as such at a showing at the University of Southern California, Bakshi stated firmly, "Fritz the Cat is not pornographic."[17] In May 1972, Variety reported that Krantz had appealed the X rating, saying "Animals having sex isn't pornography." The MPAA refused to hear the appeal.[18] The misconceptions about the film's content were eventually cleared up when it received praise from Rolling Stone and The New York Times, and the film was accepted into the 1972 Cannes Film Festival.[49] Bakshi later stated, "Now they do as much on The Simpsons as I got an X rating for Fritz the Cat."[50]

Before the film's release, American distributors attempted to cash in on the publicity garnered from the rating by rushing out dubbed versions of two other adult animated films from Japan, both of which featured an X rating in their advertising material: Senya ichiya monogatari and Kureopatora, re-titled A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra: Queen of Sex. However, neither film was actually submitted to the MPAA, and it is not likely that either feature would have received an X rating.[17] (Unlike the NC-17 rating, the MPAA never obtained a trademark on the X rating, thus any film not submitted to the MPAA for a rating can declare itself "Rated X.") The film Down and Dirty Duck was promoted with an X rating, but likewise had not been submitted to the MPAA.[51] The French-Belgian animated film Tarzoon: Shame of the Jungle initially was released with an X rating in a subtitled version, but a dubbed version released in 1979 received an R rating.[52]

Reception[edit]

Initial screenings[edit]

Fritz the Cat opened on April 12, 1972, in Hollywood and Washington, D.C.[5] Although the film only had a limited release, it went on to become a worldwide hit.[32] Against its $700,000 budget, it grossed $25 million in the United States and over $90 million worldwide,[53][54] and was at that point the most successful independent animated feature of all time.[19] The film earned $4.7 million in theater rentals in North America.[55]

In Michael Barrier's 1972 article on its production, Bakshi gives accounts of two screenings of the film. Of the reactions to the film by audiences at a preview screening in Los Angeles, Bakshi stated, "They forget it's animation. They treat it like a film. ... This is the real thing, to get people to take animation seriously." Bakshi was also present at a showing of the film at the Museum of Modern Art and remembers "Some guy asked me why I was against the revolution. The point is, animation was making people get up off their asses and get mad."[17]

The film also sparked negative reactions because of its content. "A lot of people got freaked out", says Bakshi. "The people in charge of the power structure, the people in charge of magazines and the people going to work in the morning who loved Disney and Norman Rockwell, thought I was a pornographer, and they made things very difficult for me. The younger people, the people who could take new ideas, were the people I was addressing. I wasn't addressing the whole world. To those people who loved it, it was a huge hit, and everyone else wanted to kill me."[56]

Critical reception[edit]

Critical reaction was mixed, but generally positive. Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film is "constantly funny ... [There's] something to offend just about everyone."[18] New York magazine film critic Judith Crist reviewed the film as "a gloriously funny, brilliantly pointed, and superbly executed entertainment ... [whose] target is ... the muddle-headed radical chicks and slicks of the sixties", and that it "should change the face of the animated cartoon forever".[57] Paul Sargent Clark in The Hollywood Reporter called the film "powerful and audacious",[18] and Newsweek called it "a harmless, mindless, pro-youth saga calculated to shake up only the box office".[18] The Wall Street Journal and Cue both gave the film mixed reviews.[18] Thomas Albright of Rolling Stone wrote an enthusiastic preview in the December 9, 1971 issue based on seeing thirty minutes of the film, declaring that it was "sure to mark the most important breakthrough in animation since Yellow Submarine".[58] But in a review published after its release, Albright recanted his earlier statement and wrote that the visuals were not enough to save the finished product from being a "qualified disaster" due to a "leaden plot" and a "juvenile" script that relied too heavily on tired gags and tasteless ethnic humor.[59]

Lee Beaupre wrote for The New York Times, "In dismissing the political turbulence and personal quest of the sixties while simultaneously exploiting the sexual freedom sired by that decade, Fritz the Cat truly bites the hand that fed it."[60] Film critic Andrew Osmond wrote that the epilogue hurt the film's integrity for "giving Fritz cartoon powers of survival that the film had rejected until then".[61] Patricia Erens found scenes with Jewish stereotypes "vicious and offensive" and stated, "Only the jaundiced eye of director Ralph Bakshi, which denigrates all of the characters, the hero included, makes one reflect on the nature of the attack."[62]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a score of 64%, based on 22 critic reviews, with an average rating of 5.6/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Fritz the Cat's gleeful embrace of bad taste can make for a queasy viewing experience, but Ralph Bakshi's idiosyncratic animation brings the satire and style of Robert Crumb's creation to vivid life."[63]

Crumb's response[edit]

Crumb first saw the film in February 1972, during a visit to Los Angeles with fellow underground cartoonists Spain Rodriguez, S. Clay Wilson, Robert Williams, and Rick Griffin. According to Bakshi, Crumb was dissatisfied with the film.[32] Among his criticisms, he said that he felt that Skip Hinnant was wrong for the voice of Fritz, and said that Bakshi should have voiced the character instead.[32] Crumb later said in an interview that he felt that the film was "really a reflection of Ralph Bakshi's confusion, you know. There's something real repressed about it. In a way, it's more twisted than my stuff. It's really twisted in some kind of weird, unfunny way. ... I didn't like that sex attitude in it very much. It's like real repressed horniness; he's kind of letting it out compulsively."[6] Crumb also criticized the film's condemnation of the radical left,[5] denouncing Fritz's dialogue in the final sequences of the film, which includes a quote from the Beatles song "The End", as "red-neck and fascistic"[4] and stated, "They put words into his mouth that I never would have had him say."[4]

Reportedly, Crumb filed a lawsuit to have his name removed from the film's credits.[64] San Francisco copyright attorney Albert L. Morse said that no suit was filed, but an agreement was reached to remove Crumb's name from the credits.[65] However, Crumb's name has remained in the final film since its original theatrical release.[18] Due to his distaste for the film, Crumb had "Fritz the Cat—Superstar" published in People's Comics later in 1972, in which a jealous girlfriend kills Fritz with an icepick;[16] he has refused to use the character again,[11] and wrote the filmmakers a letter saying not to use his characters in their films.[5] Crumb later cited the film as "one of those experiences I sort of block out. The last time I saw it was when I was making an appearance at a German art school in the mid-1980s, and I was forced to watch it with the students. It was an excruciating ordeal, a humiliating embarrassment. I recall Victor Moscoso was the only one who warned me 'if you don't stop this film from being made, you are going to regret it for the rest of your life'—and he was right."[66]

In a 2008 interview, Bakshi referred to Crumb as a "hustler" and stated, "He goes in so many directions that he's hard to pin down. I spoke to him on the phone. We both had the same deal, five percent. They finally sent Crumb the money and not me. Crumb always gets what he wants, including that château of his in France. ... I have no respect for Crumb. Is he a good artist? Yes, if you want to do the same thing over and over. He should have been my best friend for what I did with Fritz the Cat. I drew a good picture, and we both made out fine."[26] Bakshi also stated that Crumb threatened to disassociate himself from any cartoonist that worked with Bakshi, which would have hurt their chances at getting work published.[67]

Legacy[edit]

In addition to other animated films aimed at adult audiences, the film's success led to the production of a sequel, The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat. Although producer Krantz and voice actor Hinnant returned for the follow-up, Bakshi did not. Instead, Nine Lives was directed by animator Robert Taylor, who co-wrote the film with Fred Halliday and Eric Monte. Nine Lives was distributed by American International Pictures, and was considered inferior to its predecessor.[68] Both films have been released on DVD in the United States and Canada by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (the owners of the American International Pictures library via Orion Pictures) and the UK by Arrow Films.[69][70] Bakshi states that he felt constricted using anthropomorphic characters in Fritz, and focused solely on non-anthropomorphic characters in Heavy Traffic and Hey Good Lookin', but later used anthropomorphic characters in Coonskin.[31]

The film is widely noted in its innovation for featuring content that had not been portrayed in animation before, such as sexuality and violence, and was also, as John Grant writes in his book Masters of Animation, "the breakthrough movie that opened brand new vistas to the commercial animator in the United States",[68] presenting an "almost disturbingly accurate" portrayal "of a particular stratum of Western society during a particular era, ... as such it has dated very well."[68] The film's subject matter and its satirical approach offered an alternative to the kinds of films that had previously been presented by major animation studios.[68] Michael Barrier described Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic as "not merely provocative, but highly ambitious". Barrier described the films as an effort "to push beyond what was done in the old cartoons, even while building on their strengths".[71] It is also considered to have paved the way for future animated works for adults, including The Simpsons, Family Guy and South Park.[9]

As a result of these innovations, Fritz was selected by Time Out magazine as the 42nd greatest animated film,[72] ranked at number 51 on the Online Film Critics Society's list of the top 100 greatest animated films of all time,[73] and was placed at number 56 on Channel 4's list of the 100 Greatest Cartoons.[74] Footage from the film was edited into the music video for Guru's 2007 song "State of Clarity".[75]

Home media[edit]

Fritz the Cat along with The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat was released on VHS in 1988 by Warner Home Video through Orion Pictures. In 2001, MGM distributed the film with the sequel on DVD.[76] The film again along with its sequel was released on Blu-ray by Scorpion Releasing and Kino Lorber on October 26, 2021, featuring a new audio commentary by comic artist Stephen R. Bissette and author G. Michael Dobbs.[77][78][79]