Gaullism

Gaullism (French: Gaullisme) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic.[1] De Gaulle withdrew French forces from the NATO Command Structure, forced the removal of Allied bases from France, as well as initiated France's own independent nuclear deterrent programme. His actions were predicated on the view that France would not be subordinate to other nations.[2]

According to Serge Berstein, Gaullism is "neither a doctrine nor a political ideology" and cannot be considered either left or right. Rather, "considering its historical progression, it is a pragmatic exercise of power that is neither free from contradictions nor of concessions to momentary necessity, even if the imperious word of the general gives to the practice of Gaullism the allure of a programme that seems profound and fully realised". Gaullism is "a peculiarly French phenomenon, without doubt the quintessential French political phenomenon of the 20th century".[1]

Lawrence D. Kritzman argues that Gaullism may be seen as a form of French patriotism in the tradition of Jules Michelet. He writes: "Aligned on the political spectrum with the right, Gaullism was committed nevertheless to the republican values of the Revolution, and so distanced itself from the particularist ambitions of the traditional right and its xenophobic causes". Furthermore, "Gaullism saw as its mission the affirmation of national sovereignty and unity, which was diametrically opposed to the divisiveness created by the leftist commitment to class struggle".[3]

Gaullism was nationalistic. In the early post-WWII period, Gaullists advocated for retaining the French Empire.[4] De Gaulle shifted his stance on empire in the mid-1950s, suggesting potential federal arrangements or self-determination and membership in the French Community.[4]

Berstein writes that Gaullism has progressed in multiple stages:

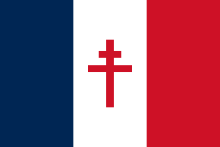

Since 1969, Gaullism has been used to describe those identified as heirs to de Gaulle's ideas.[1] The Cross of Lorraine, used by the Resistant Free France (1940–1944) during World War II, has served as the symbol of many Gaullist parties and movements, including the Rally of the French People (1947–1955), the Union for the New Republic (1958–1967), or the Rally for the Republic (1976–2002).[5]

Political legacy after de Gaulle[edit]

De Gaulle's political legacy has been profound in France and has gradually influenced the entirety of the political spectrum.[1][7] His successor as president, Georges Pompidou, consolidated Gaullism during his term from 1969 to 1974. Once-controversial Gaullist ideas have become accepted as part of the French political consensus and "are no longer the focus of political controversy." For instance, the strong presidency was maintained by all of de Gaulle's successors, including the socialist François Mitterrand (1981–1995). French independent nuclear capability and a foreign policy influenced by Gaullism–although expressed "in more flexible terms"–remains "the guiding force of French international relations."[1] During the 2017 presidential election, de Gaulle's legacy was claimed by candidates ranging from the radical left to the radical right, including Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Benoît Hamon, Emmanuel Macron, François Fillon and Marine Le Pen.[7]

According to Berstein, "It is no exaggeration to say that Gaullism has molded post-war France. At the same time, considering that the essence of Gaullist ideas are now accepted by everyone, those who wish to be the legitimate heirs of de Gaulle (e.g., Jacques Chirac of the RPR) now have an identity crisis. It is difficult for them to distinguish themselves from other political perspectives."[1] Not all Gaullist ideas have endured, however. Between the mid-1980s and the early 2000s, there have been several periods of cohabitation (1986–1988, 1993–1995, 1997–2002), in which the president and prime minister have been from different parties, a marked shift from the "imperial presidency" of de Gaulle. De Gaulle's economic policy, based on the idea of dirigisme (state stewardship of the economy), has also weakened. Although the major French banks, as well as insurance, telecommunications, steel, oil and pharmaceutical companies, were state-owned as recently as the mid-1980s, the French government has since then privatized many state assets.[8]

The following is a list of Gaullist political parties and their successors: