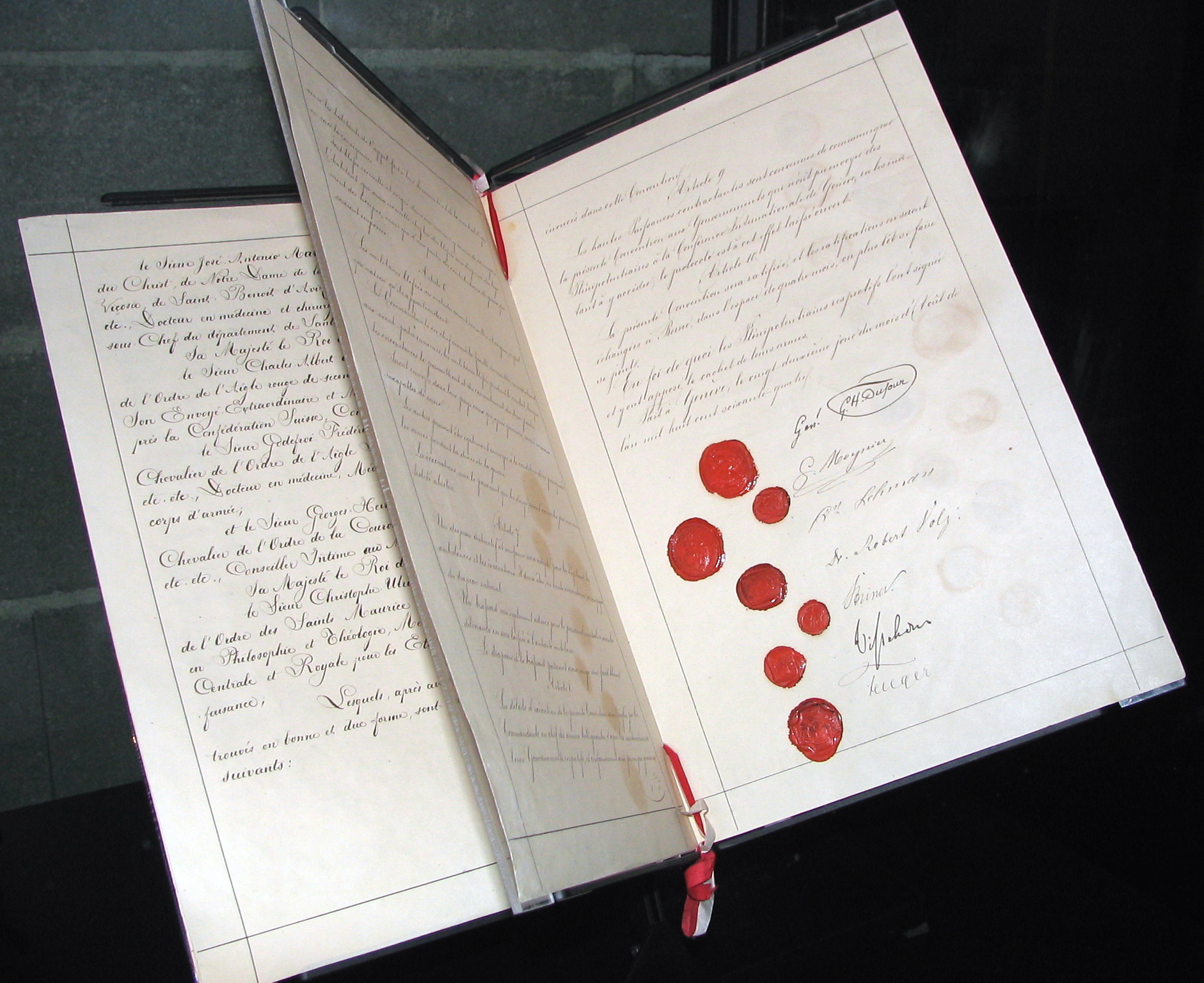

Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term Geneva Convention colloquially denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners, civilians and military personnel; establish protections for the wounded and sick; and provide protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone.[2]

Not to be confused with Geneva Conference, Geneva Protocol (disambiguation), Geneva Accords (1988), or Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.The Geneva Conventions define the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants who fulfill the criteria of being protected persons.[3] The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with reservations, by 196 countries.[4] The Geneva Conventions concern only protected non-combatants in war. The use of wartime conventional weapons is addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the 1980 Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, while the biological and chemical warfare in international armed conflicts is addressed by the 1925 Geneva Protocol.

Legacy[edit]

Although warfare has changed dramatically since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, they are still considered the cornerstone of contemporary international humanitarian law.[65] They protect combatants who find themselves hors de combat, and they protect civilians caught up in the zone of war. These treaties came into play for all recent non-international armed conflicts, including the War in Afghanistan,[66] the Iraq War, the invasion of Chechnya (1994–2017),[67] and the Russo-Georgian War. The Geneva Conventions also protect those affected by non-international armed conflicts such as the Syrian civil war.

The lines between combatants and civilians have blurred when the actors are not exclusively High Contracting Parties (HCP).[68] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, an HCP often is faced with a non-state actor,[69] as argued by General Wesley Clark in 2007.[70] Examples of such conflict include the Sri Lankan Civil War, the Sudanese Civil War, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, as well as most military engagements of the US since 2000.

Some scholars hold that Common Article 3 deals with these situations, supplemented by Protocol II (1977). These set out minimum legal standards that must be followed for internal conflicts. International tribunals, particularly the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), have clarified international law in this area.[71] In the 1999 Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic judgement, the ICTY ruled that grave breaches apply not only to international conflicts, but also to internal armed conflict. Further, those provisions are considered customary international law.

Controversy has arisen over the US designation of irregular opponents as "unlawful enemy combatants" (see also unlawful combatant), especially in the SCOTUS judgments over the Guantanamo Bay detention camp brig facility Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and Rasul v. Bush,[72] and later Boumediene v. Bush. President George W. Bush, aided by Attorneys-General John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales and General Keith B. Alexander, claimed the power, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, to determine that any person, including an American citizen, who is suspected of being a member, agent, or associate of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or possibly any other terrorist organization, is an "enemy combatant" who can be detained in U.S. military custody until hostilities end, pursuant to the international law of war.[73][74][75]

The application of the Geneva Conventions in the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) has been troublesome because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues.[76] The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under jus in bello doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POWs captured in this circumstance remains a question.

Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University,[77][78] the International Committee of the Red Cross,[79] and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.[80]

New challenges[edit]

Artificial intelligence and autonomous weapon systems, such as military robots and cyber-weapons, are creating challenges in the creation, interpretation and application of the laws of armed conflict. The complexity of these new challenges, as well as the speed in which they are developed, complicates the application of the Conventions, which have not been updated in a long time.[81][82] Adding to this challenge is the very slow speed of the procedure of developing new treaties to deal with new forms of warfare, and determining agreed-upon interpretations to existing ones, meaning that by the time a decision can be made, armed conflict may have already evolved in a way that makes the changes obsolete.