Goodwill (accounting)

In accounting, goodwill is an intangible asset recognized when a firm is purchased as a going concern. It reflects the premium that the buyer pays in addition to the net value of its other assets. Goodwill is often understood to represent the firm's intrinsic ability to acquire and retain customer business, where that ability is not otherwise attributable to brand name recognition, contractual arrangements or other specific factors. It is recognized only through an acquisition; it cannot be self-created. It is classified as an intangible asset on the balance sheet, since it can neither be seen nor touched.

Under U.S. GAAP and IFRS, goodwill is never amortized, because it is considered to have an indefinite useful life. (Private companies in the United States may elect to amortize goodwill over a period of ten years or less under an accounting alternative from the Private Company Council of the FASB.) Instead, management is responsible for valuing goodwill every year and to determine if an impairment is required. If the fair market value goes below historical cost (what goodwill was purchased for), an impairment must be recorded to bring it down to its fair market value. However, an increase in the fair market value would not be accounted for in the financial statements.

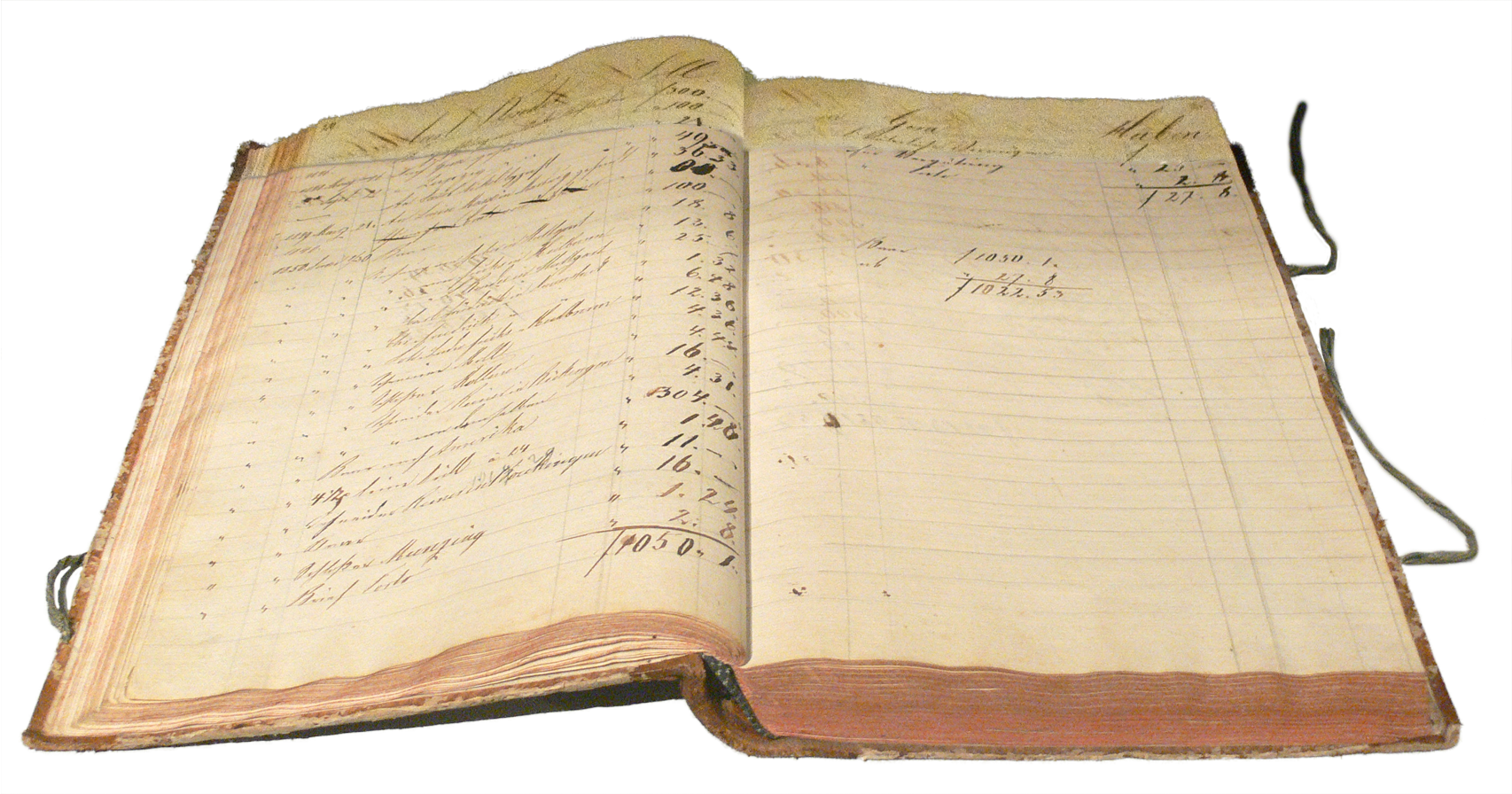

Origins[edit]

The concept of commercial goodwill developed together with the capitalist economy. In England, contracts from the 15th century onward refer to the purchase and conveyance of goodwill, roughly meaning the transfer of continuing business, as distinguished from the transfer of business property. Such agreements were initially unenforceable under the restraint of trade doctrine, which held that one could not claim property in business activity, until Broad v. Jolyffe (1620) established that restraints could be legal in exceptional cases. John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon defined the concept succinctly in 1810 as "the probability that the old customers will resort to the old place."[1]

Modern meaning[edit]

Goodwill is a special type of intangible asset that represents that portion of the entire business value that cannot be attributed to other income producing business assets, tangible or intangible.[3]

For example, a privately held software company may have net assets (consisting primarily of miscellaneous equipment and/or property, and assuming no debt) valued at $1 million, but the company's overall value (including customers and intellectual capital) is valued at $10 million. Anybody buying that company would book $10 million in total assets acquired, comprising $1 million physical assets and $9 million in other intangible assets. And any consideration paid in excess of $10 million shall be considered as goodwill. In a private company, goodwill has no predetermined value prior to the acquisition; its magnitude depends on the two other variables by definition. A publicly traded company, by contrast, is subject to a constant process of market valuation, so goodwill will always be apparent.

While a business can invest to increase its reputation, by advertising or assuring that its products are of high quality, such expenses cannot be capitalized and added to goodwill, which is technically an intangible asset. Goodwill and intangible assets are usually listed as separate items on a company's balance sheet.[4][5] In the b2b sense, goodwill may account for the criticality that exists between partners engaged in a supply chain relationship, or other forms of business relationships, where unpredictable events may cause volatilities across entire markets.[6]

Types of goodwill[edit]

There are two types of goodwill: institutional (enterprise) and professional (personal). Institutional goodwill may be described as the intangible value that would continue to inure to the business without the presence of specific owner. Professional goodwill may be described as the intangible value attributable solely to the efforts of or reputation of an owner of the business. The key difference between the two types of goodwill is whether the goodwill is transferable upon a sale to a third party without a non-competition agreement.[7]

United States practice[edit]

History and purchase vs. pooling-of-interests[edit]

Previously, companies could structure many acquisition transactions to determine the choice between two accounting methods to record a business combination: purchase accounting or pooling-of-interests accounting. Pooling-of-interests method combined the book value of assets and liabilities of the two companies to create the new balance sheet of the combined companies. It therefore did not distinguish between who is buying whom. It also did not record the price the acquiring company had to pay for the acquisition. Since 2001, U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (FAS 141) no longer allows the pooling-of-interests method.

Amortization and adjustments to carrying value[edit]

Goodwill is no longer amortized under U.S. GAAP (FAS 142).[8] FAS 142 was issued in June 2001. Companies objected to the removal of the option to use pooling-of-interests, so amortization was removed by Financial Accounting Standards Board as a concession. As of 2005-01-01, it is also forbidden under International Financial Reporting Standards. Goodwill can now only be impaired under these GAAP standards.[9]

Instead of deducting the value of goodwill annually over a period of maximal 40 years, companies are now required to determine the fair value of the reporting units, using present value of future cash flow, and compare it to their carrying value (book value of assets plus goodwill minus liabilities.) If the fair value is less than carrying value (impaired), the goodwill value needs to be reduced so the carrying value is equal to the fair value. The impairment loss is reported as a separate line item on the income statement, and new adjusted value of goodwill is reported in the balance sheet.[10]

Controversy[edit]

When the business is threatened with insolvency, investors will deduct the goodwill from any calculation of residual equity because it has no resale value.

The accounting treatment for goodwill remains controversial within both the accounting and financial industries because it is fundamentally a workaround employed by accountants to compensate for the fact that businesses when purchased are valued based on estimates of future cash flows and prices negotiated by the buyer and seller, and not on the fair value of assets and liabilities to be transferred by the seller. This creates a mismatch between the reported assets and net incomes of companies that have grown without purchasing other companies, and those that have.

While companies will follow the rules prescribed by the Accounting Standards Boards, there is not a fundamentally correct way to deal with this mismatch under the current financial reporting framework. Therefore, the accounting for goodwill will be rules based, and those rules have changed, and can be expected to continue to change, periodically along with the changes in the members of the Accounting Standards Boards. The current rules governing the accounting treatment of goodwill are highly subjective and can result in very high costs, but have limited value to investors.