Gram-positive bacteria

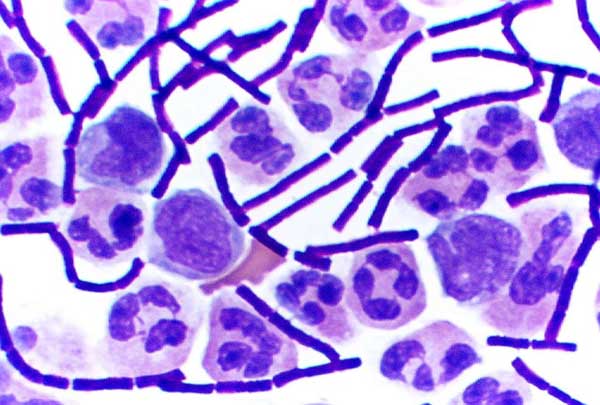

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain is used by microbiologists to place bacteria into two main categories, Gram-positive (+) and Gram-negative (-). Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan within the cell wall, and Gram-negative bacteria have a thin layer of peptidoglycan.

Gram-positive bacteria take up the crystal violet stain used in the test, and then appear to be purple-coloured when seen through an optical microscope. This is because the thick layer of peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall retains the stain after it is washed away from the rest of the sample, in the decolorization stage of the test.

Conversely, gram-negative bacteria cannot retain the violet stain after the decolorization step; alcohol used in this stage degrades the outer membrane of gram-negative cells, making the cell wall more porous and incapable of retaining the crystal violet stain. Their peptidoglycan layer is much thinner and sandwiched between an inner cell membrane and a bacterial outer membrane, causing them to take up the counterstain (safranin or fuchsine) and appear red or pink.

Despite their thicker peptidoglycan layer, gram-positive bacteria are more receptive to certain cell wall–targeting antibiotics than gram-negative bacteria, due to the absence of the outer membrane.[1]

Bacterial transformation[edit]

Transformation is one of three processes for horizontal gene transfer, in which exogenous genetic material passes from a donor bacterium to a recipient bacterium, the other two processes being conjugation (transfer of genetic material between two bacterial cells in direct contact) and transduction (injection of donor bacterial DNA by a bacteriophage virus into a recipient host bacterium).[21][22] In transformation, the genetic material passes through the intervening medium, and uptake is completely dependent on the recipient bacterium.[21]

As of 2014 about 80 species of bacteria were known to be capable of transformation, about evenly divided between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria; the number might be an overestimate since several of the reports are supported by single papers.[21] Transformation among gram-positive bacteria has been studied in medically important species such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sanguinis and in gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus.[23]

Orthographic note[edit]

The adjectives gram-positive and gram-negative derive from the surname of Hans Christian Gram; as eponymous adjectives, their initial letter can be either capital G or lower-case g, depending on which style guide (e.g., that of the CDC), if any, governs the document being written.[24] This is further explained at Gram staining § Orthographic note.