Haymarket affair

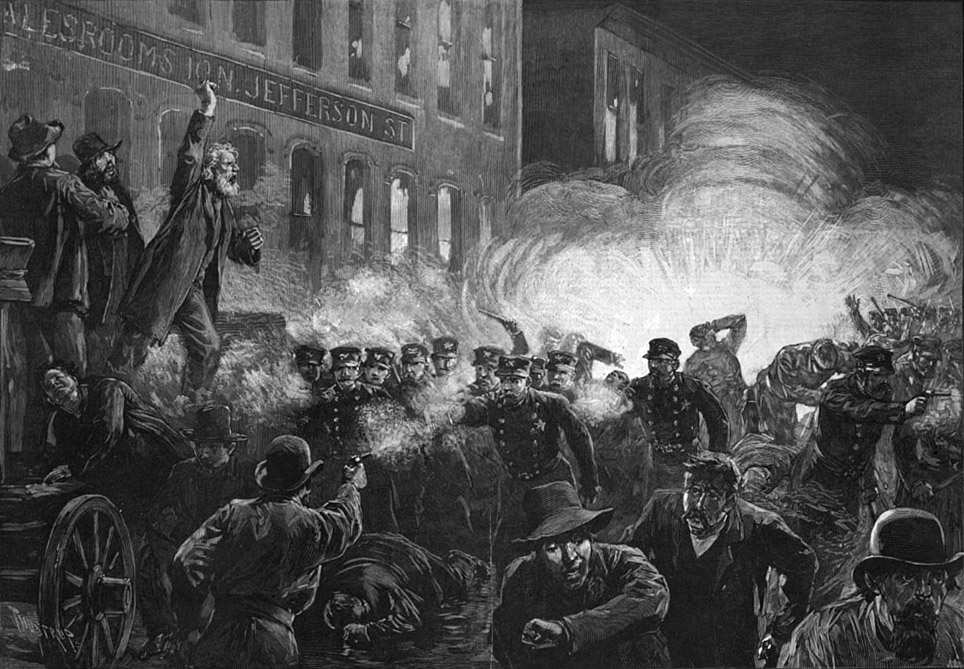

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States.[2] The rally began peacefully in support of workers striking for an eight-hour work day, the day after the events at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, during which one person was killed and many workers injured.[3] An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing retaliatory gunfire by the police caused the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.[3]

Several terms redirect here. For other uses, see 2007 London car bombs and Haymarket Riot (band).

Eight anarchists were charged with the bombing. In the internationally publicized legal proceedings against the accused, the eight were convicted of conspiracy.

The Haymarket affair is generally considered significant as the origin of International Workers' Day held on May 1,[4][5] and it was also the climax of the social unrest among the working class in America known as the Great Upheaval.

The evidence put forward in the court trial was that one of the defendants may have built the bomb, but none of those on trial had thrown it, and only two of the eight were at the Haymarket at the time.[6][7][8][9] Seven were sentenced to death and one to a term of 15 years in prison. Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby commuted two of the sentences to terms of life in prison; another died by suicide in jail before his scheduled execution. The other four were hanged on November 11, 1887.[3] In 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining defendants and criticized the trial.[10]

The site of the incident was designated a Chicago landmark in 1992,[11] and a sculpture was dedicated there in 2004. In addition, the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997 at the defendants' burial site in Forest Park.[12]

While admitting that none of the defendants was involved in the bombing, the prosecution made the argument that Lingg had built the bomb, and prosecution witnesses Harry Gilmer and Malvern Thompson tried to imply that the bomb-thrower was helped by Spies, Fischer and Schwab.[112][113] The defendants claimed they had no knowledge of the bomber at all.

Several activists, including Robert Reitzel, later hinted they knew who the bomber was.[114] Writers and other commentators have speculated about many possible suspects: