Historical criticism

Historical criticism (also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism) is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text"[1] and emphasizes a process that "delays any assessment of scripture’s truth and relevance until after the act of interpretation has been carried out".[2] While often discussed in terms of ancient Jewish, Christian, and increasingly Islamic writings, historical criticism has also been applied to other religious and secular writings from various parts of the world and periods of history.[3]

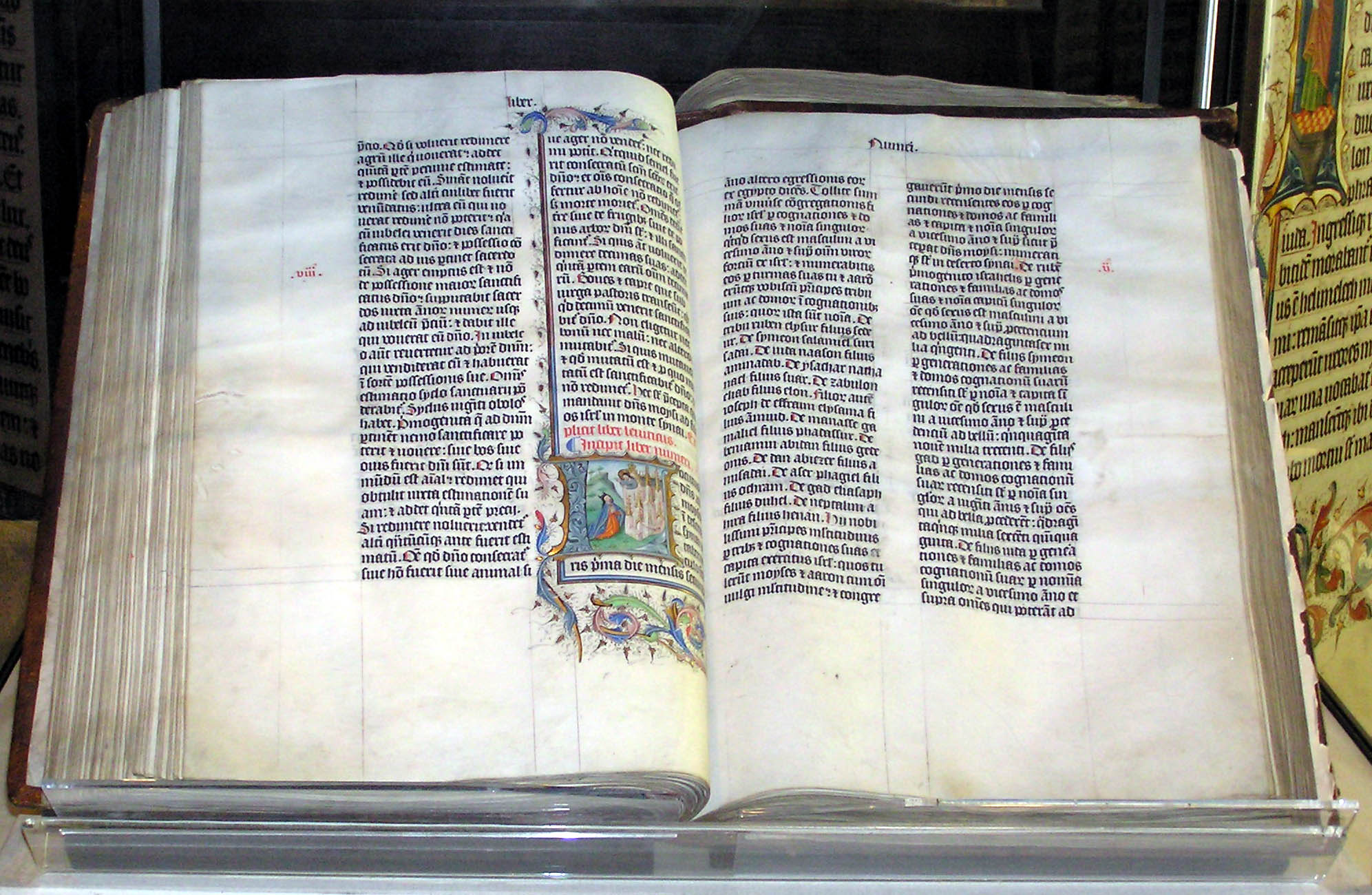

The primary goal of historical criticism is to discover the text's primitive or original meaning in its original historical context and its literal sense or sensus literalis historicus. The secondary goal seeks to establish a reconstruction of the historical situation of the author and recipients of the text. That may be accomplished by reconstructing the true nature of the events that the text describes. An ancient text may also serve as a document, record or source for reconstructing the ancient past, which may also serve as a chief interest to the historical critic. In regard to Semitic biblical interpretation, the historical critic would be able to interpret the literature of Israel as well as the history of Israel.[4] In 18th century Biblical criticism, the term "higher criticism" was commonly used in mainstream scholarship[5] in contrast to "lower criticism" (textual criticism).[6]

Historical criticism began in the 17th century and gained popular recognition in the 19th and 20th centuries. The perspective of the early historical critic was influenced by the rejection of traditional interpretations that came about with the Protestant Reformation. With each passing century, historical criticism became refined into various methodologies used today: source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, canonical criticism, and related methodologies.[7]

Evangelical objections[edit]

Beginning in the nineteenth century, effort on the part of evangelical scholars and writers was expended in opposing theories of historical critical scholars. Evangelicals at the time accused the 'higher critics' of representing their dogmas as indisputable facts. Bygone churchmen such as James Orr, William Henry Green, William M. Ramsay, Edward Garbett, Alfred Blomfield, Edward Hartley Dewart, William B. Boyce, John Langtry, Dyson Hague, D. K. Paton, John William McGarvey, David MacDill, J. C. Ryle, Charles Spurgeon and Robert D. Wilson pushed back against the judgements of historical critics. Some of these counter-views still have support in the more conservative evangelical circles today. There has never been a centralised stance on historical criticism, and Protestant denominations divided over the issue (e.g. Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy, Downgrade controversy etc.). The historical-grammatical method of biblical interpretation has been preferred by evangelicals, but is not held by the preponderance of contemporary scholars affiliated to major universities.[17] Gleason Archer Jr., O. T. Allis, C. S. Lewis,[18] Gerhard Maier, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Robert L. Thomas, F. David Farnell, William J. Abraham, J. I. Packer, G. K. Beale and Scott W. Hahn rejected the historical-critical hermeneutical method as evangelicals.

Evangelical Christians have often partly attributed the decline of the Christian faith (i.e. declining church attendance, fewer conversions to faith in Christ and biblical devotion, denudation of the Bible's supernaturalism, syncretism of philosophy and Christian revelation etc.) in the developed world to the consequences of historical criticism. Acceptance of historical critical dogmas engendered conflicting representations of Protestant Christianity.[19] The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy in Article XVI affirms traditional inerrancy, but not as a response to 'negative higher criticism.'[20]

On the other hand, attempts to revive the extreme historical criticism of the Dutch Radical School by Robert M. Price, Darrell J. Doughty and Hermann Detering have also been met with strong criticism and indifference by mainstream scholars. Such positions are nowadays confined to the minor Journal of Higher Criticism and other fringe publications.[21]