History of philosophy in Poland

The history of philosophy in Poland parallels the evolution of philosophy in Europe in general.

Overview[edit]

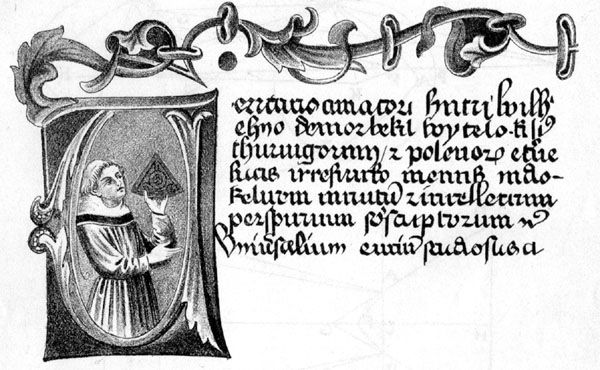

Polish philosophy drew upon the broader currents of European philosophy, and in turn contributed to their growth. Some of the most momentous Polish contributions came, in the thirteenth century, from the Scholastic philosopher and scientist Vitello, and, in the sixteenth century, from the Renaissance polymath Nicolaus Copernicus.[1]

Subsequently, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth partook in the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment, which for the multi-ethnic Commonwealth ended not long after the 1772-1795 partitions and political annihilation that would last for the next 123 years, until the collapse of the three partitioning empires in World War I.

The period of Messianism, between the November 1830 and January 1863 Uprisings, reflected European Romantic and Idealist trends, as well as a Polish yearning for political resurrection. It was a period of maximalist metaphysical systems.

The collapse of the January 1863 Uprising prompted an agonizing reappraisal of Poland's situation. Poles gave up their earlier practice of "measuring their resources by their aspirations" and buckled down to hard work and study. "[A] Positivist", wrote the novelist Bolesław Prus' friend, Julian Ochorowicz, was "anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."[2]

The twentieth century brought a new quickening to Polish philosophy. There was growing interest in western philosophical currents. Rigorously-trained Polish philosophers made substantial contributions to specialized fields—to psychology, the history of philosophy, the theory of knowledge, and especially mathematical logic.[3] Jan Łukasiewicz gained world fame with his concept of many-valued logic and his "Polish notation."[4] Alfred Tarski's work in truth theory won him world renown.[5]

After World War II, for over four decades, world-class Polish philosophers and historians of philosophy such as Władysław Tatarkiewicz continued their work, often in the face of adversities occasioned by the dominance of a politically enforced official philosophy. The phenomenologist Roman Ingarden did influential work in esthetics and in a Husserl-style metaphysics; his student Karol Wojtyła acquired a unique influence on the world stage as Pope John Paul II.