House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancaster—from which the house was named—for his second son Edmund Crouchback in 1267. Edmund had already been created Earl of Leicester in 1265 and was granted the lands and privileges of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, after de Montfort's death and attainder at the end of the Second Barons' War.[1] When Edmund's son Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, inherited his father-in-law's estates and title of Earl of Lincoln he became at a stroke the most powerful nobleman in England, with lands throughout the kingdom and the ability to raise vast private armies to wield power at national and local levels.[2] This brought him—and Henry, his younger brother—into conflict with their cousin King Edward II, leading to Thomas's execution. Henry inherited Thomas's titles and he and his son, who was also called Henry, gave loyal service to Edward's son King Edward III.

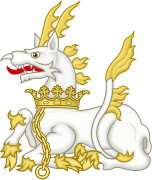

For the Toronto strip clubs, see House of Lancaster (strip clubs). For the mansion in London, see Lancaster House.House of Lancaster

1267

Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster and Leicester (first house)

John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (second house)

Extinct

Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster (first house)

Henry VI of England (second house)

England

1361 (last unbroken male heir)

1471 (extinction)

- House of Beaufort (legitimized)

- House of Somerset (legitimized)

The second house of Lancaster was descended from John of Gaunt, who married the heiress of the first house, Blanche of Lancaster. Edward III married all his sons to wealthy English heiresses rather than following his predecessors' practice of finding continental political marriages for royal princes. Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, had no male heir so Edward married his son John to Henry's heiress daughter and John's third cousin Blanche of Lancaster. This gave John the vast wealth of the House of Lancaster. Their son Henry usurped the throne in 1399, creating one of the factions in the Wars of the Roses. There was an intermittent dynastic struggle between the descendants of Edward III. In these wars, the term Lancastrian became a reference to members of the family and their supporters. The family provided England with three kings: Henry IV (r. 1399–1413), Henry V (r. 1413–1422), and Henry VI (r. 1422–1461 and 1470–1471).

The house became extinct in the male line upon the death or murder in the Tower of London of Henry VI, following the battlefield execution of his son Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, by supporters of the House of York in 1471. Lancastrian cognatic descent—from John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster's daughter Philippa—continued in the royal houses of Spain and Portugal while the Lancastrian political cause was maintained by Henry Tudor—a relatively unknown scion of the Lancastrian Beauforts—eventually leading to the establishment of the House of Tudor. The Lancastrians left a legacy through the patronage of the arts, most notably in founding Eton College and King's College, Cambridge. However, to historians' chagrin, it is Shakespeare's partly fictionalized history plays rather than medievalist scholarly research that has the greater influence on modern perceptions of the dynasty.[3]

Reign of Henry IV[edit]

There is much debate among historians about Henry's accession, in part because some see it as a cause of the Wars of the Roses. For many historians, the accession by force of the throne broke principles the Plantagenets had established successfully over two and a half centuries and allowed any magnate with sufficient power and Plantagenet blood to have ambitions to assume the throne. Richard had attempted to disinherit Henry and remove him from the succession. In response, Henry's legal advisors, led by William Thirning, dissuaded Henry from claiming the throne by right of conquest and instead look for legal justification.[29] Although Henry established a committee to investigate his assertion that his mother had legitimate rights through descent from Edmund Crouchback, who he said was the elder son of Henry III of England but was set aside because of deformity, no evidence was found. The eight-year-old Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was the heir general to Richard II by being the great-grandson of Edward III's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, and also the son of Richard's last nominated heir. In desperation, Henry's advisors made the case that Henry was heir male to Henry III and this was supported by thirteenth-century entails.[30] Mortimer's sister Anne de Mortimer married Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, son of Edward III's fourth son Edmund of Langley, consolidating Anne's place in the succession with that of the more junior House of York.[31] As a child, Mortimer was not considered a serious contender and, as an adult, he showed no interest in the throne. He instead loyally served the House of Lancaster. Mortimer informed Henry V when Conisburgh, in what was later called the Southampton Plot, attempted to place him on the throne instead of Henry's newly crowned son—their mutual cousin—leading to the execution of Conisburgh and the other plotters.[32]

Henry IV was plagued with financial problems, the political need to reward his supporters, frequent rebellions and declining health—including leprosy and epilepsy.[33] The Percy family had been some of Henry's leading supporters, defending the North from Scotland largely at their own expense, but revolted in the face of lack of reward and suspicion from Henry. Henry Percy (Hotspur) was defeated and killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury. In 1405, Hotspur's father Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, supported Richard le Scrope, Archbishop of York, in another rebellion, after which the elder Percy fled to Scotland and his estates were confiscated. Henry had Scrope executed in an act comparable to the murder of another Archbishop—Thomas Becket—by men loyal to Henry II. This would probably have led to Henry's excommunication, but the church was in the midst of the Western Schism, with competing popes keen on Henry's support; it protested but took no action.[34] In 1408, Percy invaded England once more and was killed at the Battle of Bramham Moor.[35] In Wales, Owain Glyndŵr's widespread rebellion was only suppressed with the recapture of Harlech Castle in 1409, although sporadic fighting continued until 1421.[36]

Henry IV was succeeded by his son Henry V,[37] and eventually by his grandson Henry VI in 1422.[38]