Deep vein thrombosis

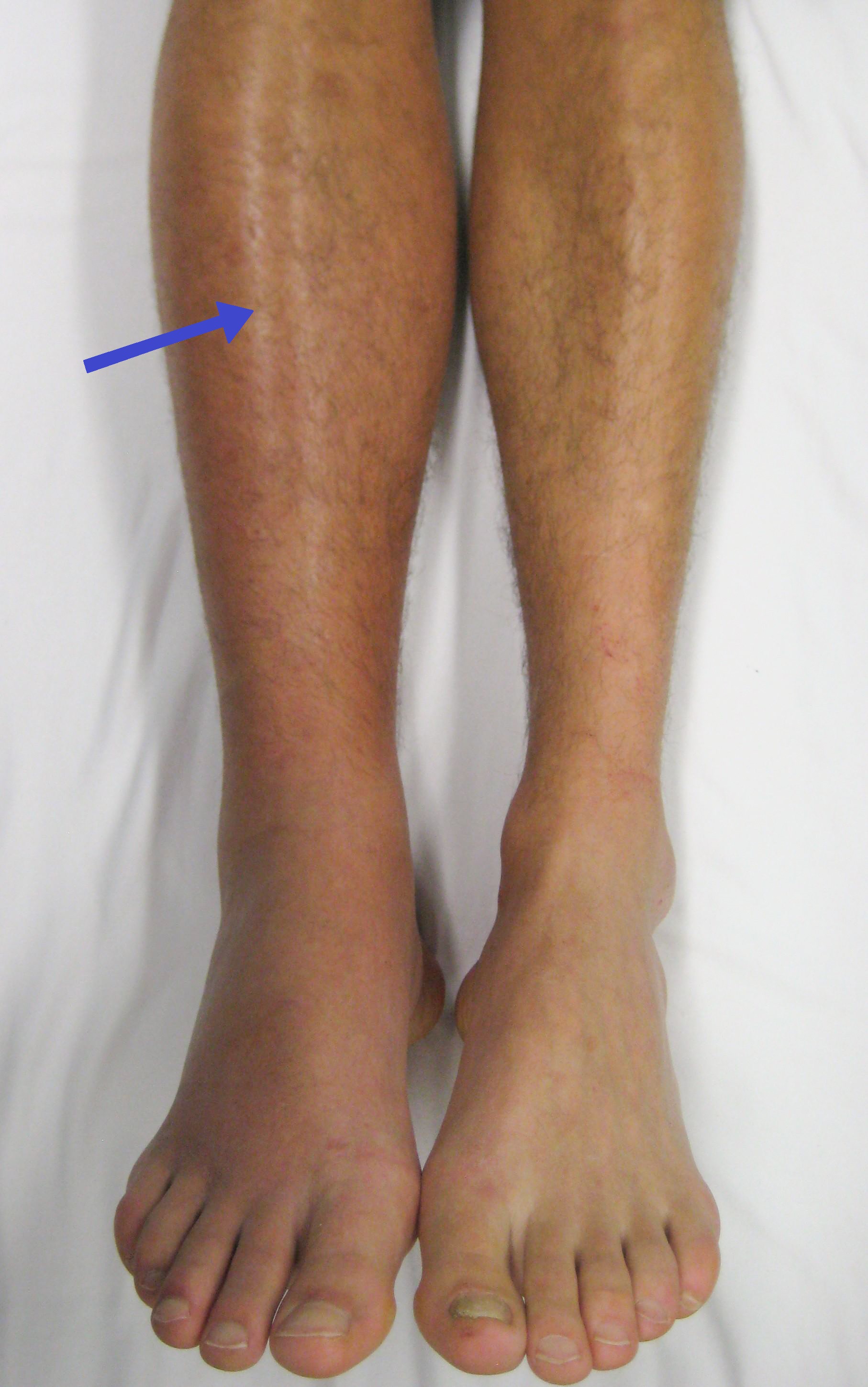

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a type of venous thrombosis involving the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs or pelvis.[9][a] A minority of DVTs occur in the arms.[11] Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and enlarged veins in the affected area, but some DVTs have no symptoms.[1]

"DVT" redirects here. For other uses, see DVT (disambiguation).Deep vein thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis

Post-thrombotic syndrome, recurrent VTE[2]

Recent surgery, older age, active cancer, obesity, infection, inflammatory diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome, personal history or family history of VTE, injuries, trauma, lack of movement, hormonal birth control, pregnancy and the period following delivery, genetic factors[3][4]

Cellulitis, ruptured Baker's cyst, hematoma, lymphedema, chronic venous insufficiency, etc.

Frequent walking, calf exercises, maintaining a healthy body weight, anticoagulants (blood thinners), intermittent pneumatic compression, graduated compression stockings, aspirin[6][7]

Anticoagulation, catheter-directed thrombolysis

From 0.8–2.7 per 1000 people per year, but populations in China and Korea are below this range[8]

The most common life-threatening concern with DVT is the potential for a clot to embolize (detach from the veins), travel as an embolus through the right side of the heart, and become lodged in a pulmonary artery that supplies blood to the lungs. This is called a pulmonary embolism (PE). DVT and PE comprise the cardiovascular disease of venous thromboembolism (VTE).[2] About two-thirds of VTE manifests as DVT only, with one-third manifesting as PE with or without DVT.[12] The most frequent long-term DVT complication is post-thrombotic syndrome, which can cause pain, swelling, a sensation of heaviness, itching, and in severe cases, ulcers.[5] Recurrent VTE occurs in about 30% of those in the ten years following an initial VTE.[3]

The mechanism behind DVT formation typically involves some combination of decreased blood flow, increased tendency to clot, changes to the blood vessel wall, and inflammation.[13] Risk factors include recent surgery, older age, active cancer, obesity, infection, inflammatory diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome, personal history and family history of VTE, trauma, injuries, lack of movement, hormonal birth control, pregnancy, and the period following birth. VTE has a strong genetic component, accounting for approximately 50 to 60% of the variability in VTE rates.[4] Genetic factors include non-O blood type, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S and the mutations of factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A. In total, dozens of genetic risk factors have been identified.[4][14]

People suspected of having DVT can be assessed using a prediction rule such as the Wells score. A D-dimer test can also be used to assist with excluding the diagnosis or to signal a need for further testing.[5] Diagnosis is most commonly confirmed by ultrasound of the suspected veins.[5] VTE becomes much more common with age. The condition is rare in children, but occurs in almost 1% of those ≥ age 85 annually.[3] Asian, Asian-American, Native American, and Hispanic individuals have a lower VTE risk than Whites or Blacks.[4][15] Populations in Asia have VTE rates at 15 to 20% of what is seen in Western countries.[16]

Using blood thinners is the standard treatment. Typical medications include rivaroxaban, apixaban, and warfarin. Beginning warfarin treatment requires an additional non-oral anticoagulant, often injections of heparin.[17][18][19] Prevention of VTE for the general population includes avoiding obesity and maintaining an active lifestyle. Preventive efforts following low-risk surgery include early and frequent walking. Riskier surgeries generally prevent VTE with a blood thinner or aspirin combined with intermittent pneumatic compression.[7]

A clinical probability assessment using the Wells score (see column in the table below) to determine if a potential DVT is "likely" or "unlikely" is typically the first step of the diagnostic process. The score is used in suspected first lower extremity DVT (without any PE symptoms) in primary care and outpatient settings, including the emergency department.[1][5] The numerical result (possible score −2 to 9) is most commonly grouped into either "unlikely" or "likely" categories.[1][5] A Wells score of two or more means DVT is considered "likely" (about a 28% chance), while those with a lower score are considered "unlikely" to have DVT (about a 6% chance).[39] In those unlikely to have DVT, a diagnosis is excluded by a negative D-dimer blood test.[1] In people with likely DVT, ultrasound is the standard imaging used to confirm or exclude a diagnosis.[5] Imaging is also needed for hospital inpatients with suspected DVT and those initially categorized as unlikely to have DVT but who have a positive D-dimer test.[1]

While the Wells score is the predominant and most studied clinical prediction rule for DVT,[39][115] it does have drawbacks. The Wells score requires a subjective assessment regarding the likelihood of an alternate diagnosis and performs less well in the elderly and those with a prior DVT. The Dutch Primary Care Rule has also been validated for use. It contains only objective criteria but requires obtaining a D-dimer value.[116] With this prediction rule, three points or less means a person is at low risk for DVT. A result of four or more points indicates an ultrasound is needed.[116] Instead of using a prediction rule, experienced physicians can make a DVT pre-test probability assessment using clinical assessment and gestalt, but prediction rules are more reliable.[1]

Compression ultrasonography for suspected deep vein thrombosis is the standard diagnostic method, and it is highly sensitive for detecting an initial DVT.[118] A compression ultrasound is considered positive when the vein walls of normally compressible veins do not collapse under gentle pressure.[39] Clot visualization is sometimes possible, but is not required.[119] Three compression ultrasound scanning techniques can be used, with two of the three methods requiring a second ultrasound some days later to rule out the diagnosis.[118] Whole-leg ultrasound is the option that does not require a repeat ultrasound,[118] but proximal compression ultrasound is frequently used because distal DVT is only rarely clinically significant.[117] Ultrasound methods including duplex and color flow Doppler can be used to further characterize the clot[117] and Doppler ultrasound is especially helpful in the non-compressible iliac veins.[119]

CT scan venography, MRI venography, or a non-contrast MRI are also diagnostic possibilities.[120] The gold standard for judging imaging methods is contrast venography, which involves injecting a peripheral vein of the affected limb with a contrast agent and taking X-rays, to reveal whether the venous supply has been obstructed. Because of its cost, invasiveness, availability, and other limitations, this test is rarely performed.[39]

Prognosis[edit]

DVT is most frequently a disease of older age that occurs in the context of nursing homes, hospitals, and active cancer.[3] It is associated with a 30-day mortality rate of about 6%, with PE being the cause of most of these deaths.[1] Proximal DVT is frequently associated with PE, unlike distal DVT, which is rarely if ever associated with PE.[39] Around 56% of those with proximal DVT also have PE, although a chest CT is not needed simply because of the presence of DVT.[1] If proximal DVT is left untreated, in the following 3 months approximately half of people will experience symptomatic PE.[9]

Another frequent complication of proximal DVT, and the most frequent chronic complication, is post-thrombotic syndrome, where individuals have chronic venous symptoms.[5] Symptoms can include pain, itching, swelling, paresthesia, a sensation of heaviness, and in severe cases, leg ulcers.[5] After proximal DVT, an estimated 20–50% of people develop the syndrome, with 5–10% experiencing severe symptoms.[165] Post-thrombotic syndrome can also be a complication of distal DVT, though to a lesser extent than with proximal DVT.[166]

In the 10 years following an initial VTE, about 30% of people will have a recurrence.[3] VTE recurrence in those with prior DVT is more likely to recur as DVT than PE.[167] Cancer[5] and unprovoked DVT are strong risk factors for recurrence.[60] After initial proximal unprovoked DVT with and without PE, 16–17% of people will have recurrent VTE in the 2 years after they complete their course of anticoagulants. VTE recurrence is less common in distal DVT than proximal DVT.[44][45] In upper extremity DVT, annual VTE recurrence is about 2–4%.[130] After surgery, a provoked proximal DVT or PE has an annual recurrence rate of only 0.7%.[60]

Epidemiology[edit]

About 1.5 out of 1000 adults a year have a first VTE in high-income countries.[168][169] The condition becomes much more common with age.[3] VTE rarely occurs in children, but when it does, it predominantly affects hospitalized children.[170] Children in North America and the Netherlands have VTE rates that range from 0.07 to 0.49 out of 10,000 children annually.[170] Meanwhile, almost 1% of those aged 85 and above experience VTE each year.[3] About 60% of all VTEs occur in those 70 years of age or older.[9] Incidence is about 18% higher in males than in females,[4] though there are ages when VTE is more prevalent in women.[15] VTE occurs in association with hospitalization or nursing home residence about 60% of the time, active cancer about 20% of the time, and a central venous catheter or transvenous pacemaker about 9% of the time.[3]

During pregnancy and after childbirth, acute VTE occurs in about 1.2 of 1000 deliveries. Despite it being relatively rare, it is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality.[160] After surgery with preventive treatment, VTE develops in about 10 of 1000 people after total or partial knee replacement, and in about 5 of 1000 after total or partial hip replacement.[171] About 400,000 Americans develop an initial VTE each year, with 100,000 deaths or more attributable to PE.[169] Asian, Asian-American, Native American, and Hispanic individuals have a lower VTE risk than Whites or Blacks.[4][15] Populations in Asia have VTE rates at 15 to 20% of what is seen in Western countries, with an increase in incidence seen over time.[16] In North American and European populations, around 4–8% of people have a thrombophilia,[89] most commonly factor V leiden and prothrombin G20210A. For populations in China, Japan, and Thailand, deficiences in protein S, protein C, and antithrombin predominate.[172] Non-O blood type is present in around 50% of the general population and varies with ethnicity, and it is present in about 70% of those with VTE.[90][173]

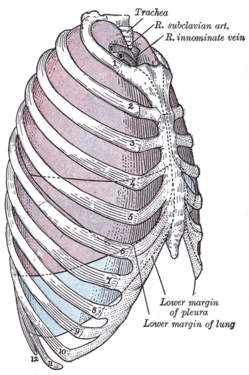

DVT occurs in the upper extremities in about 4–10% of cases,[11] with an incidence of 0.4–1.0 people out of 10,000 a year.[5] A minority of upper extremity DVTs are due to Paget–Schroetter syndrome, also called effort thrombosis, which occurs in 1–2 people out of 100,000 a year, usually in athletic males around 30 years of age or in those who do significant amounts of overhead manual labor.[69][147]

Research directions[edit]

A 2019 study published in Nature Genetics reported more than doubling the known genetic loci associated with VTE.[14] In their updated 2018 clinical practice guidelines, the American Society of Hematology identified 29 separate research priorities, most of which related to patients who are acutely or critically ill.[63] Inhibition of factor XI, P-selectin, E-selectin, and a reduction in formation of neutrophil extracellular traps are potential therapies that might treat VTE without increasing bleeding risk.[200]

![Doppler ultrasonography showing absence of flow and hyperechogenic content in a clotted femoral vein (labeled subsartorial[h]) distal to the branching point of the deep femoral vein. When compared to this clot, clots that instead obstruct the common femoral vein (proximal to this branching point) cause more severe effects due to impacting a significantly larger portion of the leg.[122]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Ultrasonography_of_deep_vein_thrombosis_of_the_femoral_vein_-annotated.jpg/459px-Ultrasonography_of_deep_vein_thrombosis_of_the_femoral_vein_-annotated.jpg)

![After treatment with catheter-directed thrombolysis, blood flow in the axillary and subclavian vein were significantly improved. Afterwards, a first rib resection allowed decompression. This reduces the risk of recurrent DVT and other sequelae from thoracic outlet compression.[147]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/A-case-of-Paget-Schroetter-syndrome-%28PSS%29-in-a-young-judo-tutor-a-case-report-13256_2016_848_Fig2_HTML.jpg)