Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

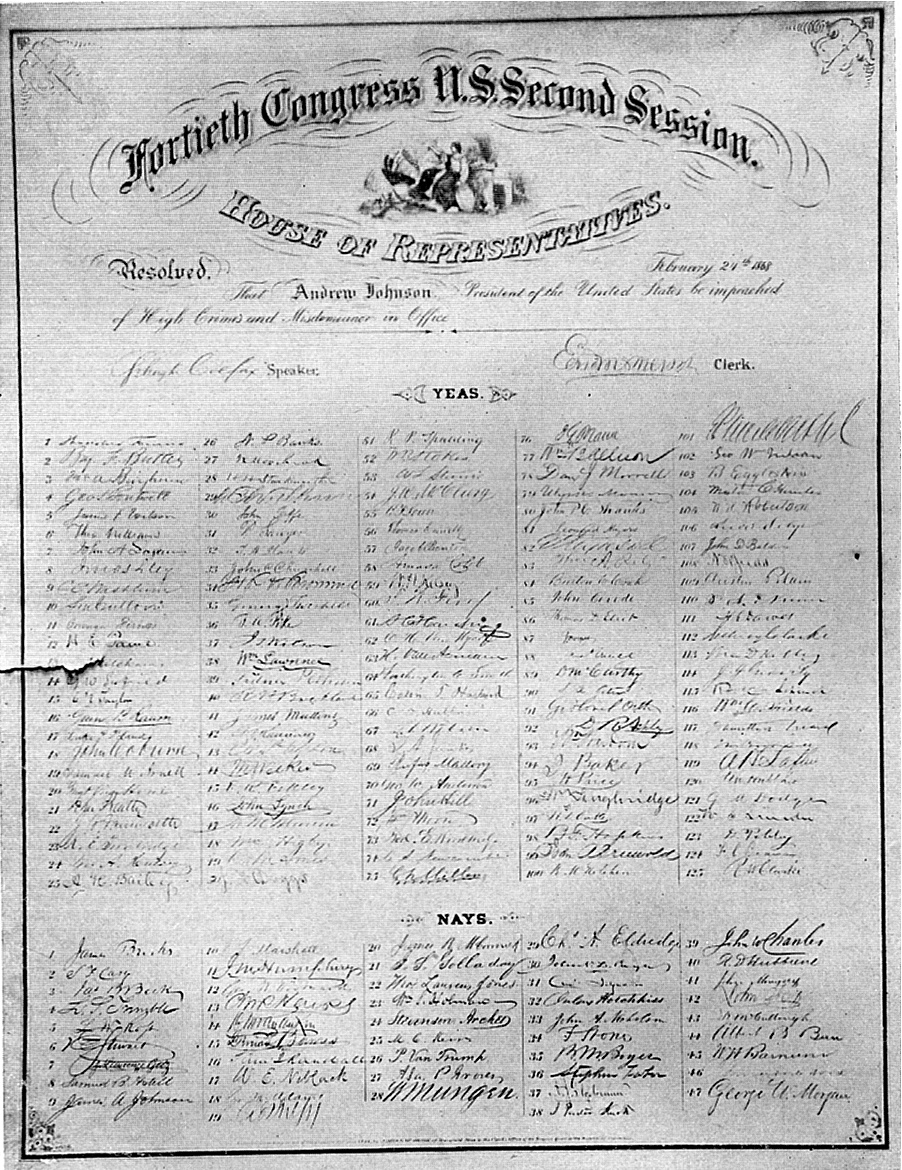

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson was initiated on February 24, 1868, when the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution to impeach Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, for "high crimes and misdemeanors". The alleged high crimes and misdemeanors were afterwards specified in eleven articles of impeachment adopted by the House on March 2 and 3, 1868. The primary charge against Johnson was that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act. Specifically, that he had acted to remove from office Edwin Stanton and to replace him with Brevet Major General Lorenzo Thomas as secretary of war ad interim. The Tenure of Office Act had been passed by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto with the primary intent of protecting Stanton from being fired without the Senate's consent. Stanton often sided with the Radical Republican faction and did not have a good relationship with Johnson.

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

February 24, 1868 to May 26, 1868

Acquitted by the U.S. Senate, remained in office

Violating the Tenure of Office Act by attempting to replace Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war, while Congress was not in session and other alleged abuses of presidential power

126

47

Approved resolution of impeachment

Article XI

35 "guilty"

19 "not guilty"

Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction)

Article II

35 "guilty"

19 "not guilty"

Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction)

Article III

35 "guilty"

19 "not guilty"

Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction)

Johnson was the first United States president to be impeached. After the House formally adopted the articles of impeachment, they forwarded them to the United States Senate for adjudication. The trial in the Senate began on March 5, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding. On May 16, the Senate voted against convicting Johnson on one of the articles, with its 35–19 vote in favor of conviction falling one vote short of the necessary two-thirds majority. A 10-day recess of the Senate trial was called before reconvening to convict him on additional articles. On May 26, the Senate voted against convicting the president on two more articles by margins identical to the first vote. After this, the trial was adjourned sine die without votes being held on the remaining eight articles of impeachment.

The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson had important political implications for the balance of federal legislative-executive power. It maintained the principle that Congress should not remove the president from office simply because its members disagreed with him over policy, style, and administration of the office. It also resulted in diminished presidential influence on public policy and overall governing power, fostering a system of governance which future-President Woodrow Wilson referred to in the 1880s as "Congressional Government".

Later analysis of Johnson's impeachment[edit]

In 1887, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed by Congress, and subsequent rulings by the United States Supreme Court seemed to support Johnson's position that he was entitled to fire Stanton without congressional approval. The Supreme Court's ruling on a similar piece of later legislation in Myers v. United States (1926) affirmed the ability of the president to remove a postmaster without congressional approval, and the dictum of the majority opinion stated, "that the Tenure of Office Act of 1867...was invalid".[99]

Lyman Trumbull of Illinois (one of the ten Republican senators whose refusal to vote for conviction prevented Johnson's removal from office) noted in his speech explaining his vote for acquittal, that, had Johnson been convicted, the main source of the American presidency's political power (the freedom for a president to disagree with the Congress without consequences) would have been destroyed, as would Constitution's system of checks and balances.[100] Indeed, the impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson had long-lasting effects on the separation of powers. It established the rule that Congress should not remove the president due to a conflict over the structure of their administration. It also resulted in diminished presidential influence on public policy and overall governing power, fostering a system of governance which future-President Woodrow Wilson referred to in the 1880s as "Congressional Government".[6]