Ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is the same, regardless of the species of origin, but ivory contains structures of mineralised collagen.[1] The trade in certain teeth and tusks other than elephant is well established and widespread; therefore, "ivory" can correctly be used to describe any mammalian teeth or tusks of commercial interest which are large enough to be carved or scrimshawed.[2]

For other uses, see Ivory (disambiguation).

Besides natural ivory, ivory can also be produced synthetically,[3][4][5][6][7] hence (unlike natural ivory) not requiring the retrieval of the material from animals. Tagua nuts can also be carved like ivory.[8]

The trade of finished goods of ivory products has its origins in the Indus Valley. Ivory is a main product that is seen in abundance and was used for trading in Harappan civilization. Finished ivory products that were seen in Harappan sites include kohl sticks, pins, awls, hooks, toggles, combs, game pieces, dice, inlay and other personal ornaments.

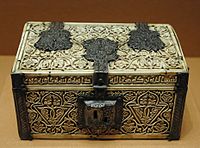

Ivory has been valued since ancient times in art or manufacturing for making a range of items from ivory carvings to false teeth, piano keys, fans, and dominoes.[9] Elephant ivory is the most important source, but ivory from mammoth, walrus, hippopotamus, sperm whale, orca, narwhal and warthog are used as well.[10][11] Elk also have two ivory teeth, which are believed to be the remnants of tusks from their ancestors.[12]

The national and international trade in natural ivory of threatened species such as African and Asian elephants is illegal.[13] The word ivory ultimately derives from the ancient Egyptian âb, âbu ('elephant'), through the Latin ebor- or ebur.[14]

Mechanical characteristics[edit]

While many uses of ivory are purely ornamental in nature, it often must be carved and manipulated into different shapes to achieve the desired form. Other applications, such as ivory piano keys, introduce repeated wear and surface handling of the material. It is therefore essential to consider the mechanical properties of ivory when designing alternatives.

Elephant tusks are the animal's incisors, so the composition of ivory is unsurprisingly similar to that of teeth in several other mammals. It is composed of dentine, a biomineral composite constructed from collagen fibers mineralized with hydroxyapatite.[1] This composite lends ivory the impressive mechanical properties—high stiffness, strength, hardness, and toughness—required for its use in the animal's day-to-day activities. Ivory has a measured hardness of 35 on the Vickers scale, exceeding that of bone. It also has a flexural modulus of 14 GPa, a flexural strength of 378 MPa a fracture toughness of 2.05 MPam1/2.[29] These measured values indicate that ivory mechanically outperforms most of its most common alternatives, including celluloid plastic and polyethylene terephthalate.[29]

Ivory's mechanical properties result from the microstructure of the dentine tissue. It is thought that the structural arrangement of mineralized collagen fibers could contribute to the checkerboard-like Schreger pattern observed in polished ivory samples.[1] This is often used as an attribute in ivory identification. As well as being an optical feature, the Schreger pattern could point towards a micropattern well-designed to prevent crack propagation by dispersing stresses.[29] Additionally, this intricate microstructure lends a strong anisotropy to ivory's mechanical characteristics. Separate hardness measurements on three orthogonal tusk directions indicated that circumferential planes of tusk had up to 25% greater hardness than radial planes of the same specimen.[30] During hardness testing, inelastic and elastic recovery was observed on circumferential planes while the radial planes displayed plastic deformation.[30] This implies that ivory has directional viscoelasticity. These anisotropic properties can be explained by the reinforcement of collagen fibers in the composite oriented along the circumference.[30]