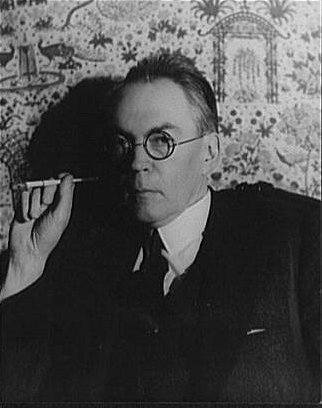

James Branch Cabell

James Branch Cabell (/ˈkæbəl/; April 14, 1879 – May 5, 1958) was an American author of fantasy fiction and belles-lettres. Cabell was well-regarded by his contemporaries, including H. L. Mencken, Edmund Wilson, and Sinclair Lewis. His works were considered escapist and fit well in the culture of the 1920s, when they were most popular. For Cabell, veracity was "the one unpardonable sin, not merely against art, but against human welfare."[1][2]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__call_to_action.textDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__subtitleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

James Branch Cabell

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Although escapist, Cabell's works are ironic and satirical. Mencken disputed Cabell's claim to romanticism and characterized him as "really the most acidulous of all the anti-romantics. His gaudy heroes ... chase dragons precisely as stockbrockers play golf." According to Louis D. Rubin, Cabell saw art as an escape from life, but found that, once the artist creates his ideal world, it is made up of the same elements that make the real one.[1]

Interest in Cabell declined in the 1930s, a decline that has been attributed in part to his failure to move out of his fantasy niche despite the onset of World War II. Alfred Kazin said that "Cabell and Hitler did not inhabit the same universe".[1]

The library at Virginia Commonwealth University is named after Cabell.

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#3__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

In 1970, Virginia Commonwealth University, also located in Richmond, named its main campus library "James Branch Cabell Library" in his honor. In the 1970s, Cabell's personal library and personal papers were moved from his home on Monument Avenue to the James Branch Cabell Library. Consisting of some 3,000 volumes, the collection includes manuscripts; notebooks and scrapbooks; periodicals in which Cabell's essays, reviews and fiction were published; his correspondence with noted writers including H. L. Mencken, Ellen Glasgow, Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser; correspondence with family, friends, editors and publishers, newspaper clippings, photographs, periodicals, criticisms, printed material; publishers' agreements; and statements of sales. The collection resides in the Special Collections and Archives department of the library.[8]

The VCU undergraduate literary journal at the university is named Poictesme after the fictional province in his cycle Biography of the Life of Manuel.

More recently, VCU spent over $50 million to expand and modernize the James Branch Cabell Library to further entrench it as the premier library in the Greater Richmond Area and one of the top landmark libraries in the United States.[9] In 2016 Cabell Library won the New Landmark Library Award.[10]

The Library Journal's website provides a virtual walking tour of the new James Branch Cabell Library.[11]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#5__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Cabell's work was highly regarded by a number of his peers, including Mark Twain, Sinclair Lewis, H. L. Mencken, Joseph Hergesheimer, and Jack Woodford. Although now largely forgotten by the general public, his work was remarkably influential on later authors of fantasy fiction. James Blish was a fan of Cabell's works, and for a time edited Kalki, the journal of the Cabell Society. Robert A. Heinlein was greatly inspired by Cabell's boldness, and originally described his own book Stranger in a Strange Land as "a Cabellesque satire". A later work, Job: A Comedy of Justice, derived its title from Jurgen and contains appearances by Jurgen and the Slavic god Koschei.[13] Charles G. Finney's fantasy The Circus of Dr. Lao was influenced by Cabell's work.[14] The Averoigne stories of Clark Ashton Smith are, in background, close to those of Cabell's Poictesme. Jack Vance's Dying Earth books show considerable stylistic resemblances to Cabell; Cugel the Clever in those books bears a strong resemblance, not least in his opinion of himself, to Jurgen. Cabell was also a major influence on Neil Gaiman,[15] acknowledged as such in the rear of Gaiman's novels Stardust and American Gods.

Cabell maintained a close and lifelong friendship with well-known Richmond writer Ellen Glasgow, whose house on West Main Street was only a few blocks from Cabell's family home on East Franklin Street. They corresponded extensively between 1923 and Glasgow's death in 1945 and over 200 of their letters survive. Cabell dedicated his 1927 novel Something About Eve to her, and she in turn dedicated her book They Stooped to Folly: A Comedy of Morals (1929) to Cabell. In her autobiography, Glasgow also gave considerable thanks to Cabell for his help in the editing of her Pulitzer Prize-winning book In This Our Life (1941). However, late in their lives, friction developed between the two writers as a result of Cabell's critical 1943 review of Glasgow's novel A Certain Measure.[5]

Cabell also admired the work of the Atlanta-based writer Frances Newman, though their correspondence was cut short by her death in 1928. In 1929, Cabell supplied the preface to Newman's collected letters.[16]

From 1969 through 1972, the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series returned six of Cabell's novels to print, and elevated his profile in the fantasy genre. Today, many more of his works are available from Wildside Press.

Cabell's three-character one-act play The Jewel Merchants was used for the libretto of an opera by Louis Cheslock which premiered in 1940.[17]

Michael Swanwick published a critical monograph on Cabell's work, which argues for the continued value of a few of Cabell's works—notably Jurgen, The Cream of the Jest, and The Silver Stallion—while acknowledging that some of his writing has dated badly. Swanwick places much of the blame for Cabell's obscurity on Cabell himself, for authorizing the 18-volume Storisende uniform edition of the Biography of the Life of Manuel, including much that was of poor quality and ephemeral. This alienated admirers and scared off potential new readers. "There are, alas, an infinite number of ways for a writer to destroy himself," Swanwick wrote. "James Branch Cabell chose one of the more interesting. Standing at the helm of the single most successful literary career of any fantasist of the twentieth century, he drove the great ship of his career straight and unerringly onto the rocks."[18]

Other book-length studies on Cabell were written during the period of his fame by Hugh Walpole,[19] W. A. McNeill,[20] and Carl van Doren.[21] Edmund Wilson tried to rehabilitate his reputation with a long essay in The New Yorker.[22]

Notes

Bibliography

Further reading

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

April 14, 1879

Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

May 5, 1958 (aged 79)

Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

Author