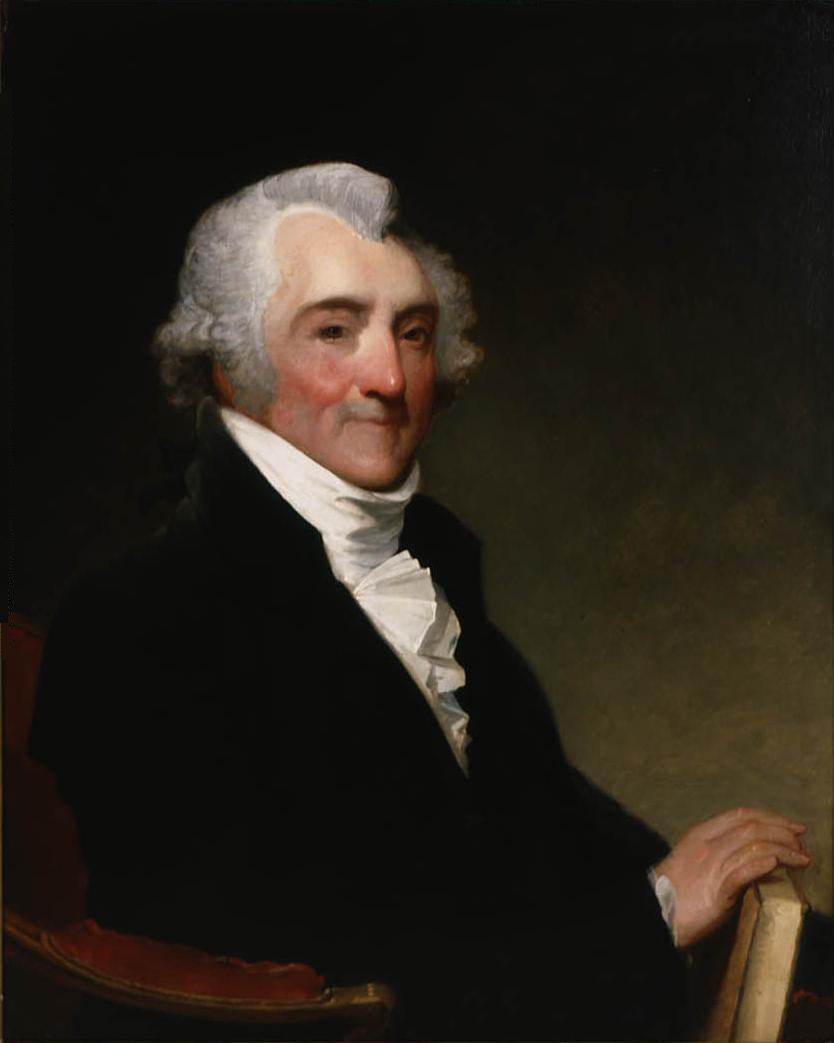

James Sullivan (governor)

James Sullivan (April 22, 1744 – December 10, 1808) was an American lawyer and politician in Massachusetts. He was an early associate justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, served as the state's attorney general for many years, and as governor of the state from 1807 until his death.

James Sullivan

Levi Lincoln Sr.

Levi Lincoln Sr. (acting)

April 22, 1744

Berwick, Province of Massachusetts Bay (present-day Maine)

December 10, 1808 (aged 64)

Boston, Massachusetts

American

- Mehitable Odiorne

- Martha Langdon

Sullivan was born and raised in Berwick, Maine (then part of Massachusetts), and studied law with his brother John. After establishing a successful law practice, he became actively involved in the Massachusetts state government during the American Revolutionary War, and was appointed to the state's highest court in March 1776. He was involved in drafting the state constitution and the state's ratifying convention for the United States Constitution. After resigning from the bench in 1782 he returned to private practice, and was appointed Attorney General in 1790. During his years as judge and attorney general he was responsible for drafting and revising much of the state's legislation as part of the transition from British rule to independence. While attorney general he worked with the commission that established the border between Maine and New Brunswick, and prosecuted several high-profile murder cases.

Sullivan was a political partisan, supporting the Democratic-Republican Party and subscribing to Jeffersonian republican ideals. He supported John Hancock and Samuel Adams in their political careers, and was a frequent contributor, often under one of many pseudonyms, to political dialogue in the state's newspapers. He ran unsuccessfully for governor several times before finally winning the office in 1807. He died in office during his second term.

In addition to his political pursuits Sullivan engaged in charitable and business endeavors. He was a leading proponent of the Middlesex Canal and the first bridge between Boston and Cambridge, and was instrumental in the development of Boston's first public water supply. He was the founding president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and held membership in a variety of other charitable organizations. He wrote one of the first histories of his native Maine, and a legal text on land titles. Legal historian Charles Warren calls him one of the most important legal figures of the time in Massachusetts.[1]

Business, economic development, and charity[edit]

In addition to his political and legal activities, Sullivan engaged in a wide variety of civic and charitable work. He was a founding member and the first president of the Massachusetts Historical Society,[59] was a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[60] and was involved with the Massachusetts Humane Society, the Society for the Propagation of the Faith among the Indians, and a charitable society that supported Congregationalist ministers.[61]

Sullivan was a major moving force and leading director of the company that oversaw the Middlesex Canal (construction of which began in 1793). The canal connected the Merrimack River at present-day Lowell (then still East Chelmsford) to the port of Boston, ending roughly at Sullivan Square, which is named in his honor.[62] He was deeply involved in the canal, purchasing the necessary land and supervising the construction. At the same time he was also involved in the company formed to build the first bridge across the Charles River connecting Boston to Cambridge, and was instrumental in the development of Boston's first public water supply, a wooden aqueduct from Jamaica Pond.[63]

Family and legacy[edit]

Sullivan's brothers were active participants in the Revolutionary War. John, Daniel, and Ebenezer, all served in the Continental Army. John served with some distinction until he retired from the army to enter New Hampshire politics in 1779; Ebenezer was captured in the Battle of The Cedars in 1776, and spent some time as a captive among the Mohawk, where he was subjected to torture;[64][65] Daniel was also captured in action and died aboard a British prison ship.[66] Sullivan, Maine is named for his brother Daniel, one of the early settlers of that area,[67] and several places in New Hampshire are named for John.[68] In 1808, while Sullivan was governor, a small fortification now known as Fort Sullivan was constructed in Eastport, Maine.[69] Who it is named for is uncertain: one early Eastport historian states that John and James are both likely candidates, preferring John for his association with General Henry Dearborn, who ordered the fort's construction.[70]

Sullivan and his first wife Hettie had nine children, two of whom died young, and one son who died in 1787 due to the hardships of militia service during Shays' Rebellion. Hettie died in 1786, and he afterward married Martha Langdon, the widowed sister of New Hampshire politician John Langdon.[71]

Sullivan's enduring interest in Maine led him to write The History of the District of Maine (published in 1795), the first work to document that history.[72] Maine historian Charles Clark writes that Sullivan's History, while neither thoroughly researched nor particularly well written, is an "un-self-conscious expression of romantic nationalism" that is "picturesque, romantic, [and] inspired".[10] Sullivan also predicted that Maine would eventually separate from Massachusetts, because "it is so large and populous, and its situation so peculiar, that it cannot remain long" a part of the other state.[73]