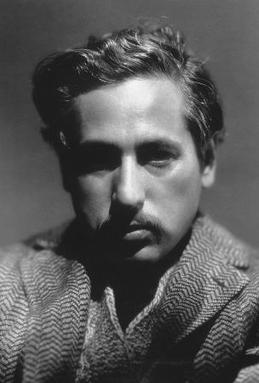

Josef von Sternberg

Josef von Sternberg (German: [ˈjoːzɛf fɔn ˈʃtɛʁnbɛʁk]; born Jonas Sternberg; May 29, 1894 – December 22, 1969) was an Austrian-born filmmaker whose career successfully spanned the transition from the silent to the sound era, during which he worked with most of the major Hollywood studios. He is best known for his film collaboration with actress Marlene Dietrich in the 1930s, including the highly regarded Paramount/UFA production The Blue Angel (1930).[1]

Josef von Sternberg

December 22, 1969 (aged 75)

1925–1957

Nicholas Josef von Sternberg

Sternberg's finest works are noteworthy for their striking pictorial compositions, dense décor, chiaroscuro illumination, and relentless camera motion, endowing the scenes with emotional intensity.[2] He is also credited with having initiated the gangster film genre with his silent era movie Underworld (1927).[3][4] Sternberg's themes typically offer the spectacle of an individual's desperate struggle to maintain their personal integrity as they sacrifice themselves for lust or love.[5]

He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932).[6]

Shortly before his death in 1969, his autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, was published.

Biography[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

Josef von Sternberg was born Jonas Sternberg to an impoverished Orthodox Jewish family in Vienna, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[7] When Sternberg was three years old, his father Moses Sternberg, a former soldier in the army of Austria-Hungary, moved to the United States to seek work. Sternberg's mother, Serafine (née Singer), a circus performer as a child [8] joined Moses in America in 1901 with her five children when Sternberg was seven.[9][10] On his emigration, von Sternberg is quoted as saying, "On our arrival in the New World we were first detained on Ellis Island where the immigration officers inspected us like a herd of cattle."[11] Jonas attended public school until the family, except Moses, returned to Vienna three years later. Throughout his life, Sternberg carried vivid memories of Vienna and nostalgia for some of his "happiest childhood moments."[12][13]

The elder Sternberg insisted upon a rigorous study of the Hebrew language, limiting his son to religious studies on top of his regular schoolwork.[14] Biographer Peter Baxter, citing Sternberg's memoirs, reports that "his parents' relationship was far from happy: his father was a domestic tyrant and his mother eventually fled her home in order to escape his abuse."[15] Sternberg's early struggles, including these "childhood traumas" would inform the "unique subject matter of his films."[16][17][18]

Early career[edit]

In 1908, when Jonas was fourteen, he returned with his mother to Queens, New York, and settled in the United States.[19] He acquired American citizenship in 1908.[20] After a year, he stopped attending Jamaica High School and began working in various occupations, including millinery apprentice, door-to-door trinket salesman and stock clerk at a lace factory.[21] At the Fifth Avenue lace outlet, he became familiar with the ornate textiles with which he would adorn his female stars and embellish his mise-en-scène.[22][23]

In 1911, when he turned seventeen, the now "Josef" Sternberg, became employed at the World Film Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey. There, he "cleaned, patched and coated motion picture stock" – and served evenings as a movie theatre projectionist. In 1914, when the company was purchased by actor and film producer William A. Brady, Sternberg rose to chief assistant, responsible for "writing [inter]titles and editing films to cover lapses in continuity" for which he received his first official film credits.[24][25]

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he joined the US Army and was assigned to the Signal Corps headquartered in Washington, D.C., where he photographed training films for recruits.[26][23][27]

Shortly after the war, Sternberg left Brady's Fort Lee operation and embarked on a peripatetic existence in America and Europe offering his skills "as cutter, editor, writer and assistant director" to various film studios.[26][23]

Later career[edit]

Between 1959 and 1963, Sternberg taught a course on film aesthetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, based on his own works. His students included undergraduate Jim Morrison and graduate student Ray Manzarek, who went on to form the rock group The Doors shortly after receiving their respective degrees in 1965. The group recorded songs referring to Sternberg, with Manzarek later characterizing Sternberg as "perhaps the greatest single influence on The Doors."[274]

When not working in California, Sternberg lived in a house that he built for himself in Weehawken, New Jersey.[275][276] He collected contemporary art and was also a philatelist, and he developed an interest in the Chinese postal system which led to him studying the Chinese language.[277] He was often a juror at film festivals.[277]

Sternberg wrote an autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965); the title was drawn from an early film comedy. Variety described it as a "bitter reflection on how a master artisan can be ignored and bypassed by an art form to which he had contributed so much."[277] He had a heart attack and was admitted to Midway Hospital Medical Center in Hollywood and died within a week on December 22, 1969, aged 75.[277][278] He was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Westwood, California near several film studios.

Comments by contemporaries[edit]

Scottish-American screenwriter Aeneas MacKenzie: "To understand what Sternberg is attempting to do, one must first appreciate that he imposes the limitations of the visual upon himself: he refuses to obtain any effect whatsoever save by means of pictorial composition. That is the fundamental distinction between von Sternberg and all other directors. Stage acting he declines, cinema in its conventional aspect he despises as mere mechanics, and dialogue he employs primarily for its value as integrated sound. The screen is his medium – not the camera. His purpose is to reveal the emotional significance of a subject by a series of magnificent canvases".[279]

American film actress and dancer Louise Brooks: "Sternberg, with his detachment, could look at a woman and say 'this is beautiful about her and I'll leave it ... and this is ugly about her and I'll eliminate it'. Take away the bad and leave what is beautiful so she's complete ... He was the greatest director of women that ever, ever was".[280]

American actor Edward Arnold: "It may be true that [von Sternberg] is a destroyer of whatever egotism an actor possesses, and that he crushes the individuality of those he directs in pictures ... the first days filming Crime and Punishment ... I had the feeling through the whole production of the picture that he wanted to break me down ... to destroy my individuality ... Probably anyone working with Sternberg over a long period would become used to his idiosyncrasies. Whatever his methods, he got the best he could out of his actors ... I consider that part of the Inspector General one [of] the best I have ever done in the talkies".[281]

American film critic Andrew Sarris: "Sternberg resisted the heresy of acting autonomy to the very end of his career, and that resistance is very likely one of the reasons his career was foreshortened".[282]