Lateral geniculate nucleus

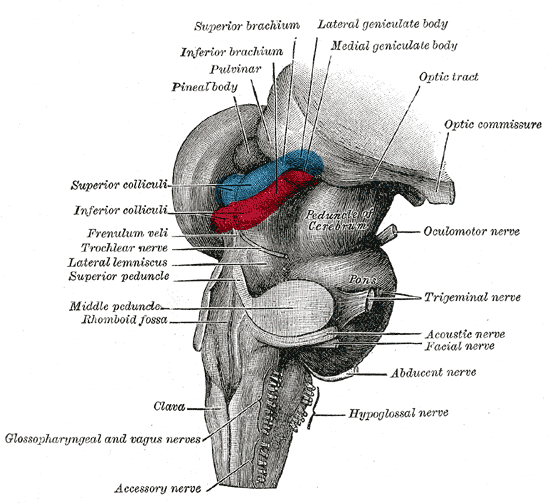

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral projection of the thalamus where the thalamus connects with the optic nerve. There are two LGNs, one on the left and another on the right side of the thalamus. In humans, both LGNs have six layers of neurons (grey matter) alternating with optic fibers (white matter).

"LGN" redirects here. For other uses, see LGN (disambiguation).Lateral geniculate nucleus

corpus geniculatum laterale

LGN

The LGN receives information directly from the ascending retinal ganglion cells via the optic tract and from the reticular activating system. Neurons of the LGN send their axons through the optic radiation, a direct pathway to the primary visual cortex. In addition, the LGN receives many strong feedback connections from the primary visual cortex.[1] In humans as well as other mammals, the two strongest pathways linking the eye to the brain are those projecting to the dorsal part of the LGN in the thalamus, and to the superior colliculus.[2]

Both the LGN in the right hemisphere and the LGN in the left hemisphere receive input from each eye. However, each LGN only receives information from one half of the visual field. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) from the inner halves of each retina (the nasal sides) decussate (cross to the other side of the brain) through the optic chiasma (khiasma means "cross-shaped"). RGCs from the outer half of each retina (the temporal sides) remain on the same side of the brain. Therefore, the right LGN receives visual information from the left visual field, and the left LGN receives visual information from the right visual field. Within one LGN, the visual information is divided among the various layers as follows:[8]

This description applies to the LGN of many primates, but not all. The sequence of layers receiving information from the ipsilateral and contralateral (opposite side of the head) eyes is different in the tarsier.[9] Some neuroscientists suggested that "this apparent difference distinguishes tarsiers from all other primates, reinforcing the view that they arose in an early, independent line of primate evolution".[10]

Input[edit]

The LGN receives input from the retina and many other brain structures, especially visual cortex.

The principal neurons in the LGN receive strong inputs from the retina. However, the retina only accounts for a small percentage of LGN input. As much as 95% of input in the LGN comes from the visual cortex, superior colliculus, pretectum, thalamic reticular nuclei, and local LGN interneurons. Regions in the brainstem that are not involved in visual perception also project to the LGN, such as the mesencephalic reticular formation, dorsal raphe nucleus, periaqueuctal grey matter, and the locus coeruleus.[11] The LGN also receives some inputs from the optic tectum (known as the superior colliculus in mammals).[12] These non-retinal inputs can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.[11]

Output[edit]

Information leaving the LGN travels out on the optic radiations, which form part of the retrolenticular portion of the internal capsule.

The axons that leave the LGN go to V1 visual cortex. Both the magnocellular layers 1–2 and the parvocellular layers 3–6 send their axons to layer 4 in V1. Within layer 4 of V1, layer 4cβ receives parvocellular input, and layer 4cα receives magnocellular input. However, the koniocellular layers, intercalated between LGN layers 1–6 send their axons primarily to the cytochrome-oxidase rich blobs of layers 2 and 3 in V1.[13] Axons from layer 6 of visual cortex send information back to the LGN.

Studies involving blindsight have suggested that projections from the LGN travel not only to the primary visual cortex but also to higher cortical areas V2 and V3. Patients with blindsight are phenomenally blind in certain areas of the visual field corresponding to a contralateral lesion in the primary visual cortex; however, these patients are able to perform certain motor tasks accurately in their blind field, such as grasping. This suggests that neurons travel from the LGN to both the primary visual cortex and higher cortex regions.[14]