Materia medica

Materia medica (lit.: 'medical material/substance') is a Latin term from the history of pharmacy for the body of collected knowledge about the therapeutic properties of any substance used for healing (i.e., medications). The term derives from the title of a work by the Ancient Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides in the 1st century AD, De materia medica, 'On medical material' (Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hylēs iatrikēs, in Greek).

The term materia medica was used from the period of the Roman Empire until the 20th century,[1] but has now been generally replaced in medical education contexts by the term pharmacology. The term survives in the title of the British Medical Journal's "Materia Non Medica" column.

Ancient civilizations[edit]

Ancient Egypt[edit]

The earliest known writing about medicine was a 110-page Egyptian papyrus. It was supposedly written by the god Thoth in about 16 BC. The Ebers papyrus is an ancient recipe book dated to approximately 1552 BC. It contains a mixture of magic and medicine with invocations to banish disease and a catalogue of useful plants, minerals, magic amulets and spells.[2] The most famous Egyptian physician was Imhotep, who lived in Memphis around 2500 B.C. Imhotep's materia medica consisted of procedures for treating head and torso injuries, tending of wounds, and prevention and curing of infections, as well as advanced principles of hygiene.

Ancient India[edit]

In India, the Ayurveda is traditional medicine that emphasizes plant-based treatments, hygiene, and balance in the body's state of being. Indian materia medica included knowledge of plants, where they grow in all season, methods for storage and shelf life of harvested materials. It also included directions for making juice from vegetables, dried powders from herb, cold infusions and extracts.[3]

Ancient China[edit]

The earliest Chinese manual of materia medica, the Shennong Bencao Jing (Shennong Emperor's Classic of Materia Medica), was compiled in the 1st century AD during the Han dynasty, attributed to the mythical Shennong. It lists some 365 medicines, of which 252 are herbs. Earlier literature included lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by the Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments found in the Mawangdui tomb, which was sealed in 168 BC. Succeeding generations augmented the Shennong Bencao Jing, as in the Yaoxing Lun (Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs), a 7th-century Tang dynasty treatise on herbal medicine.

Ancient Greece[edit]

Hippocrates[edit]

In Greece, Hippocrates (born 460 BC) was a philosopher later known as the Father of Medicine. He founded a school of medicine that focused on treating the causes of disease rather than its symptoms. Disease was dictated by natural laws and therefore could be treated through close observation of symptoms. His treatises, Aphorisms and Prognostics, discuss 265 drugs, the importance of diet and external treatments for diseases.[3]

Theophrastus[edit]

Theophrastus (390–280 BC) was a disciple of Aristotle and a philosopher of natural history, considered by historians as the Father of Botany. He wrote a treatise entitled Historia Plantarium about 300 BC. It was the first attempt to organize and classify plants, plant lore, and botanical morphology in Greece. It provided physicians with a rough taxonomy of plants and details of medicinal herbs and herbal concoctions.[4]

Galen[edit]

Galen was a philosopher, physician, pharmacist and prolific medical writer. He compiled an extensive record of the medical knowledge of his day and added his own observations. He wrote on the structure of organs, but not their uses; the pulse and its association with respiration; the arteries and the movement of blood; and the uses of theriacs. "In treatises such as On Theriac to Piso, On Theriac to Pamphilius, and On Antidotes, Galen identified theriac as a sixty-four-ingredient compound, able to cure any ill known".[5] His work was rediscovered in the 15th century and became the authority on medicine and healing for the next two centuries. His medicine was based on the regulation of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) and their properties (wet, dry, hot, and cold).[6]

Medieval[edit]

Islamic[edit]

Avicenna (980–1037 AD) was a Persian philosopher, physician, and Islamic scholar. He wrote about 40 books on medicine. His two most famous books are The Canon of Medicine and The Book of Healing, used in medieval universities as medical textbooks. He did much to popularize the connection between Greek and Arabic medicine, translating works by Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen into Arabic. Avicenna stressed the importance of diet, exercise, and hygiene. He also was the first to describe parasitic infection, to use urine for diagnostic purposes and discouraged physicians from the practice of surgery because it was too base and manual.[2]

European[edit]

In medieval Europe, medicinal herbs and plants were cultivated in monastery and nunnery gardens beginning about the 8th century. Charlemagne gave orders for the collection of medicinal plants to be grown systematically in his royal garden. This royal garden was an important precedent for botanical gardens and physic gardens that were established in the 16th century. It was also the beginning of the study of botany as a separate discipline. In about the 12th century, medicine and pharmacy began to be taught in universities.[4]

Shabbethai Ben Abraham, better known as Shabbethai Donnolo, (913–c.982) was a 10th-century Italian Jew and the author of an early Hebrew text, Antidotarium. It consisted of detailed drug descriptions, medicinal remedies, practical methods for preparing medicine from roots. It was a veritable glossary of herbs and drugs used during the medieval period. Donnollo was widely travelled and collected information from Arabic, Greek and Roman sources.[2]

In the Early and High Middle Ages Nestorian Christians were banished for their heretical views that they carried to Asia Minor. The Greek text was translated into Syriac when pagan Greek scholars fled east after Constantine’s conquest of Byzantium,

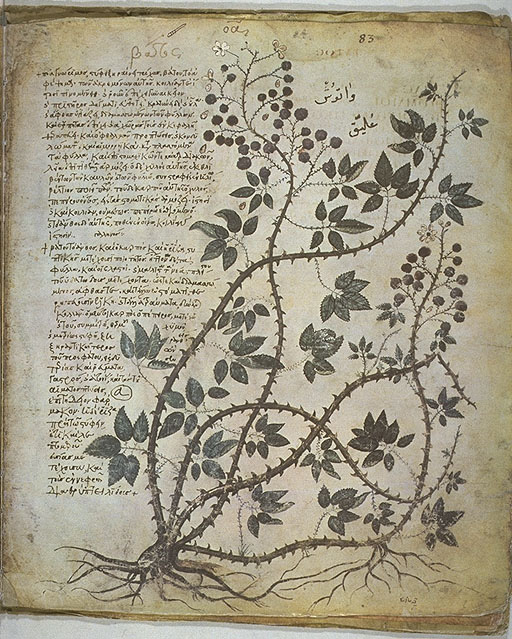

Stephanos (son of Basilios, a Christian living in Baghdad under the Khalif Motawakki) made an Arabic translation of De Materia Medica from the Greek in 854. In 948 the Byzantine Emperor Romanus II, son and co-regent of Constantine Porphyrogenitos, sent a beautifully illustrated Greek manuscript of De materia medica to the Spanish Khalif, Abd-Arrahman III. In 1250, Syriac scholar Bar Hebraeus prepared an illustrated Syriac version, which was translated into Arabic.[7][10][11]

"Materia non medica"[edit]

The ancient phrase survives in modified form in the British Medical Journal's long-established "Materia Non Medica" column, the title indicating non-medical material that doctors wished to report from their travels and other experiences. For example, in June 1977, the journal contained "Materia Non Medica" reports on an exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery by a London physician, the making of matches by hand in an Indian village by a missionary general practitioner, and a cruise to Jamaica by a University of the West Indies lecturer in medicine.[38]