Mattachine Society

The Mattachine Society (/ˈmætəʃiːn/), founded in 1950, was an early national gay rights organization in the United States,[1] preceded by several covert and open organizations, such as Chicago's Society for Human Rights.[2] Communist and labor activist Harry Hay formed the group with a collection of male friends in Los Angeles to protect and improve the rights of gay men. Branches formed in other cities, and by 1961 the Society had splintered into regional groups.

Formation

At the beginning of gay rights protest, news on Cuban prison work camps for homosexuals inspired Mattachine Society to organize protests at the United Nations and the White House in 1965.[3][4]

Affiliations[edit]

Most of the Mattachine founders were communists.[22][23] As the Red Scare progressed, the association with communism concerned some members as well as supporters and Hay, a dedicated member of the CPUSA for 15 years, stepped down as the Society's leader. Others were similarly ousted, and the leadership structure became influenced less by communism,[24] replaced by a moderate ideology similar to that espoused by the liberal reformist civil rights organizations that existed for African Americans.

The Mattachine Society existed as a single national organization headquartered first in Los Angeles and then, beginning around 1956, in San Francisco. Outside of Los Angeles and San Francisco, chapters were established in New York; Washington, D.C.; Chicago; and other locales. Due to internal disagreements, the national organization disbanded in 1961. The San Francisco national chapter retained the name "Mattachine Society", while the New York chapter became "Mattachine Society of New York, Inc" and was commonly known by its acronym MSNY. Other independent groups using the name Mattachine were formed in Washington, D.C. (Mattachine Society of Washington, 1961),[25] in Chicago (Mattachine Midwest, 1965),[26] and in Buffalo (Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, 1970).[27] In 1963 Congressman John Dowdy introduced a bill which resulted in congressional hearings to revoke the license for solicitation of funds of the Mattachine Society of Washington; the license was not revoked.[28]

A largely amicable split within the national Society in 1952 resulted in a new organization called ONE, Inc. ONE admitted women and, together with Mattachine, provided help to the Daughters of Bilitis in the launching of that group's magazine, The Ladder, in 1956. The Daughters of Bilitis were an independent lesbian organization who occasionally worked with the predominantly male Mattachine Society.[29]

The Janus Society grew out of lesbian and gay activists meeting regularly, beginning in 1961, in hopes of forming a Mattachine Society chapter. The group was not officially recognized as such a chapter, however, and so instead named itself the Janus Society of Delaware Valley. In 1964 they renamed themselves the Janus Society of America due to their increasing national visibility.[30]

In January 1962 East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO) was established, with its formative membership including the Mattachine Society chapters in New York and Washington D.C., the Janus Society, and the Daughters of Bilitis chapter in New York. ECHO was meant to facilitate cooperation between homophile organizations and outside administrations.[31] In 1964, ECHO secured a $500 settlement from the Manger Hamilton hotel, following the abrupt cancellation of ECHO's conference at the hotel. This out-of-court resolution was presented by Frank Kameny as a clear message to the homophile community – a demonstration that they would not tolerate interference, and any infringements on their rights would be addressed through legal means.[32]

On the eve of January 1, 1965, several homophile organizations in San Francisco, California - including Mattachine, the Daughters of Bilitis, the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, and the Society for Individual Rights - held a fund-raising ball for their mutual benefit at California Hall on Polk Street.[33] San Francisco police had agreed not to interfere; however, on the evening of the ball, the police surrounded the building and focused numerous Klieg lights on its entrance. As each of the 600 plus persons entering the ball approached the entrance, the police took their photographs.[33] Police vans were parked in plain view near the entrance to the ball.[33] Evander Smith, a (gay) lawyer for the groups organizing the ball, and gay lawyer Herb Donaldson tried to stop the police from conducting the fourth "inspection" of the evening; both were arrested, along with two heterosexual lawyers - Elliott Leighton and Nancy May - who were supporting the rights of the participants to gather at the ball.[33] But twenty-five of the most prominent lawyers in San Francisco joined the defense team for the four lawyers, and the judge directed the jury to find the four not-guilty before the defense had even had a chance to begin their argumentation when the case came to court.[33] This event has been called "San Francisco's Stonewall" by some historians;[33] the participation of such prominent litigators in the defense of Smith, Donaldson and the other two lawyers marked a turning point in gay rights on the West Coast of the United States.[34]

Decline[edit]

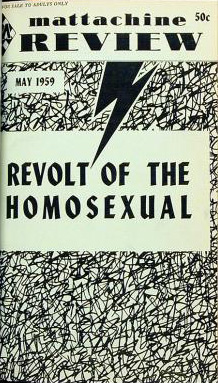

Following the Jennings trial, the group expanded rapidly, with founders estimating membership in California by May 1953 at over 2,000 with as many as 100 people joining a typical discussion group. Membership diversified, with more women and people from a broader political spectrum becoming involved. With that growth came concern about the radical left slant of the organization. In particular, Hal Call and others out of San Francisco along with Ken Burns from Los Angeles wanted Mattachine to amend its constitution to clarify its opposition to so-called "subversive elements" and to affirm that members were loyal to the United States and its laws (which declared homosexuality illegal). In an effort to preserve their vision of the organization, the Fifth Order members revealed their identities and resigned their leadership positions at Mattachine's May 1953 convention. With the founders gone, Call, Burns and other like-minded individuals stepped into the leadership void,[35] and Mattachine officially adopted non-confrontation as an organizational policy. Some historians argue that these changes reduced the effectiveness of this newly organized Mattachine and led to a precipitous drop in membership and participation.[36] Other historians contend that the Mattachine Society between 1953 and 1966 was enormously effective as it published a magazine, developed relationships with allies in the fight for homosexual equality, and influenced public opinion on the topic too.[37]

During the 1960s, the various unaffiliated Mattachine Societies, especially the Mattachine Society in San Francisco and MSNY, were among the foremost gay rights groups in the United States, but beginning in the middle 1960s and, especially, following the Stonewall riots of 1969, they began increasingly to be seen as too traditional, and not willing enough to be confrontational. Like the divide that occurred within the Civil Rights Movement, the late 1960s and the 1970s brought a new generation of activists, many of whom felt that the gay rights movement needed to endorse a larger and more radical agenda to address other forms of oppression, the Vietnam War, and the sexual revolution. Several unaffiliated entities that went under the name Mattachine eventually lost support or fell prey to internal division.

In 1973 Hal Call opened the Cinemattachine, a venue showing both Mattachine newsreels and pornographic movies. The Cinemattachine was an extension of the Mattachine Society's Sex Education Film Series and branded as being presented by both The Mattachine Society and The Seven Committee. In 1976 a venue with the name Cinemattachine Los Angeles at the ONE opened. The same screenings as the San Francisco establishment were shown there. Mattachine co-founder Chuck Rowland indicated that he did not feel that Call associating this venue with The Mattachine Society was appropriate.[38]