Mesoamerican calendars

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

These calendars have been dated to early as ca. 1100 BCE. By 500 BCE at the latest, the essentials were fully defined and functional. 260-day calendars are still used in the Guatemalan highlands,[2] Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.[3]

The importance of aboriginal calendars in ritual and other aspects of Mesoamerican life was noted by many missionary priests, travelers, and colonial administrators, and later by ethnographers who described and recorded the cultures of contemporary Mesoamerican ethnic groups.[4]

Types of calendars[edit]

Among the various calendar systems in use, two were particularly central and widespread across Mesoamerica. Common to all recorded Mesoamerican cultures, and the most important, was the 260-day calendar, a ritual calendar with no confirmed correlation to astronomical or agricultural cycles.[5] Apparently the earliest Mesoamerican calendar to be developed was known by a variety of local terms, and its named components and the glyphs used to depict them were culture-specific. However, it is clear that type of calendar functioned in essentially the same way across cultures, and across the chronological periods when it was maintained.

The second of the major calendars was one representing a 365-day period approximating the tropical year, known sometimes as the "vague year".[6] Because it was an approximation, over time the seasons and the true tropical year gradually "wandered" with respect to this calendar, owing to the accumulation of the differences in length. There is little hard evidence to suggest that the ancient Mesoamericans used any intercalary days to bring their calendar back into alignment. However, there is evidence to show Mesoamericans were aware of this gradual shifting, which they accounted for in other ways without amending the calendar itself.

These two 260- and 365-day calendars could also be synchronised to generate the Calendar Round, a period of 18980 days or approximately 52 years. The completion and observance of this Calendar Round sequence was of ritual significance to a number of Mesoamerican cultures.

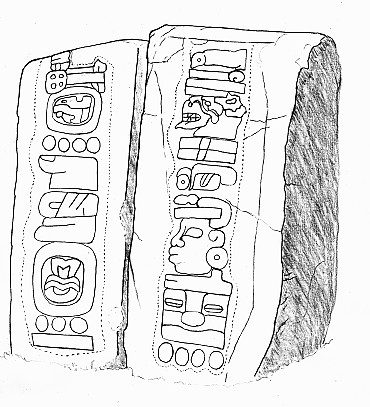

A third major calendar form known as the Long Count is found in the inscriptions of several Mesoamerican cultures, most famously those of the Maya civilization who developed it to its fullest extent during the Classic period (ca. 200–900 CE). The Long Count provided the ability to uniquely identify days over a much longer period of time, by combining a sequence of day-counts or cycles of increasing length, calculated or set from a particular date in the mythical past. Most commonly, five such higher-order cycles in a modified vigesimal (base-20) count were used.

The use of Mesoamerican calendrics is one of the cultural traits that Paul Kirchhoff used in his original formulation to define Mesoamerica as a culture area.[7] Therefore, the use of Mesoamerican calendars is specific to Mesoamerica and is not found outside its boundaries.[8]

Since the sixteenth century, most communities have lost both of these once universal calendars, but one—or, rarely, both—has survived in diverse linguistic groups through the twentieth century.[9]

Calendar Round[edit]

Since both the 260-day and the 365-day calendar repeat, approximately every 52 years they reach a common end, and a new Calendar Round begins. This 52-year cycle was the most important for most Mesoamericans, with the apparent exception of the Maya elite until the end of the Classic Era, who gave equal importance to the long count calendar.[18] According to their mythology, at the end of one of these 52-year cycles the world would be destroyed by the gods, as it had been, three times in the Popul Vuh and four times for the Aztecs. While waiting for this to happen, all fire was extinguished, utensils were destroyed to symbolize new beginnings, people fasted and rituals were carried out. This was known as the New Fire Ceremony. When dawn broke on the first day of the new cycle, torches were lit in the temples and brought out to light new fires everywhere, and ceremonies of thanksgiving were performed.[19]

Calendar Wheels[edit]

The term calendar wheel generally refers to Colonial-period images that display cycles of time in a circular format. Central Mexican calendar wheels incorporate the eighteen annual festivals or the 52-year cycle. In the Maya area, calendar wheels depict a cycle of 13 K'atuns. The only known pre-Hispanic K'atuns wheel appears on a stone turtle from Mayapán.[20]

The earliest known Colonial-period calendar wheel is actually depicted in a square format, on pages 21 and 22 of the Codex Borbonicus, an Aztec screenfold that divides the 52-year cycle into two parts. The Codex Aubin, also known as the Codex of 1576, shows the 52-year calendar in a rectangular format on a single page. Most other calendar wheels use a circular format. The Boban calendar wheel, an early sixteenth-century calendar on native paper, depicts the Central Mexican cycle of eighteen festivals in clockwise rotation, with Arabic numerals used to total the number of days; virtually all the text is in Nahuatl. Some paired festivals share the same glyph, but they are represented in different sizes, the first being the “small feast” and the second the “great feast.” In the center, a 7 Rabbit date (1538) appears with text and images that refer to Tetzcocan town officers.[21]

Religion and calendrics[edit]

Lords of the day[edit]

In the post-classic Aztec calendar, there were 13 Lords of the Day. These were gods (and goddesses) who each represented one of the 13 days in the trecenas of the 260-day calendar. The same god always represented the same day. Quetzalcohuatl (The feathered serpent), for example, always accompanied the 9th day.

Other cycles[edit]

Other calendar cycles were also recorded, such as a lunar calendar, as well as the cycles of other astronomical objects, most importantly Venus.[24]