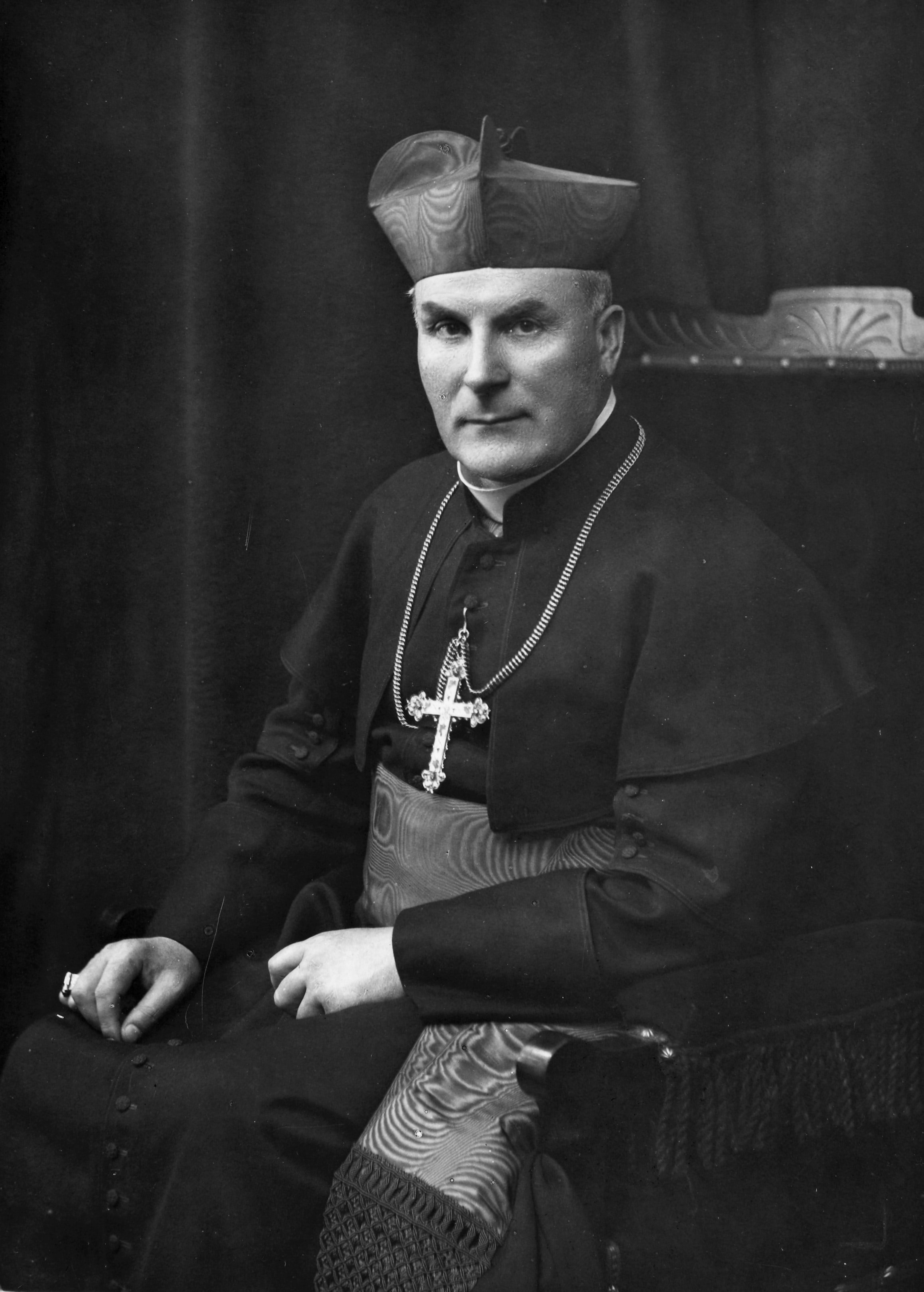

Michael von Faulhaber

Michael Ritter von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Munich for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 1952. Created Cardinal in 1921, von Faulhaber remained an outspoken monarchist and denounced the Weimar Republic as rooted in "perjury and treason" against the German Empire during a speech at the 62nd German Catholics' Day of 1922.[1][2] Cardinal von Faulhaber was a senior member and co-founder of the Amici Israel, a priestly association founded in Rome in 1926 with the goal of working toward the Jewish people's conversion to Roman Catholicism, while also seeking to combat antisemitism within the Church.[3]

Michael von Faulhaber

24 July 1917

3 September 1917

12 June 1952

Cardinal-Priest of S. Anastasia

1 August 1892

by Franz Joseph von Stein

19 February 1911

by Franziskus von Bettinger

7 March 1921

by Benedict XV

Cardinal-Priest

12 June 1952 (aged 83)

Munich, Bavaria, West Germany

Bishop of Speyer (1911–1917)

vox temporis vox Dei (the voice of the time is the voice of God)

After the Nazi Party seized control of German government in 1933, Cardinal von Faulhaber recognized the new Nazi government as legitimate, required Catholic clergy to be loyal to the government and maintained diplomatic bridges between the regime and the Church, while simultaneously condemning certain Nazi policies, including religious persecution of members of the clergy, and actively supporting anti-Nazi German Catholics such as Fritz Gerlich and other persecuted persons.[4] In 1937, Cardinal von Faulhaber was involved in drafting the anti-Nazi encyclical Mit brennender Sorge.[5] Von Faulhaber ordained Joseph Ratzinger (future Pope Benedict XVI) as a priest in 1951, and was the last surviving Cardinal appointed by Pope Benedict XV.

Life until after the First World War[edit]

Michael Faulhaber was born in Klosterheidenfeld, Bavaria, the third of seven children of the baker Michael Faulhaber (1831–1900) and his wife Margarete (1839–1911). He was educated at gymnasiums in Schweinfurt and Würzburg. In 1887-88 he was an Officer Cadet in the Bavarian army.[6] In 1889 he entered the Kilianeum (Catholic) Seminary in Würzburg and was ordained on 1 August 1892. Faulhaber was a priest in Würzburg from 1892 until 1910, serving there for six years. His studies included a specialisation in the early Christian writer Tertullian. In 1895 he graduated from his studies with a doctorate in theology. From 1894 to 1896, he was prefect of the Kilianeum Seminary. From 1896 to 1899, he was engaged in studying manuscripts at the Vatican and other Italian museums. From 1899 to 1903, he was privatdocent in Greek palaeography, Biblical archaeology, homiletics, and exegesis of the Psalms, at the University of Würzburg. In 1900 he visited England to study manuscripts of early Christian literature, spending one semester at Oxford. In 1902 he visited Spain for a similar purpose.[6] In 1903 he became professor of theology at the University of Strasbourg. He also wrote a number of articles for the Catholic Encyclopedia.[7]

In 1910, Faulhaber was appointed Bishop of Speyer and invested as such on 19 February 1911. On 1 March 1913, he was appointed a Knight of the Merit Order of the Bavarian Crown by Prince Regent Ludwig; in accordance with the statutes of this order, Faulhaber was ennobled with the style of "Ritter von Faulhaber". In 1916 he won the Iron Cross (as the first clergyman in the German Empire) at the Western Front for his frontline support of troops by acting as a military chaplain.[8] In 1917, his appointment as Archbishop of Munich followed. In 1921 he became a Cardinal, with the title of Cardinal-Priest of Sant'Anastasia, and at his death was the last surviving Cardinal appointed by Pope Benedict XV.[9]

Faulhaber felt little allegiance to the Weimar Republic. At the national Catholic conference (Katholikentag) of 1922 in Munich, he declared that the Weimar Republic was a "perjury and betrayal", because it had arrived through the overthrow of the legitimate civil authorities, the German royal houses, and had included in its constitution the separation of church and state. The declaration disturbed Catholics who were committed to the Weimar Republic, but Cardinal von Faulhaber had already praised the German Empire a few months earlier during the Requiem Mass of the last King of Bavaria, Ludwig III.[10]

Faulhaber publicised, and supported by creating an institutional link for the association, the work of Amici Israël. He supported the group by distributing its writings, saying "we must ensure wide distribution of the writings of the Amici Israel" and admonishing preachers to steer clear of any statements that "might sound in any way anti-Semitic" – this even though, "he himself was somewhat tainted by anti-Semitic stereotypes that placed Jews in the same category as Freemasons and Socialists."[11] Faulhaber was friends with the group's promoter, Sophie Francisca van Leer;[12] its special aim was to seek changes to the Good Friday prayer and some of its Latin phrases such as pro perfidis Judaeis (for treacherous Jews) and judaicam perfidiam (Jewish treachery) and sought the cessation of the deicide accusation against Jews. It was dissolved in March 1928 on the decree of the Vatican's Congregation of the Holy Office on the grounds that its perspectives were not in keeping with the spirit of the Church.[13]

Faulhaber and the Nazi Party[edit]

Rise of the Nazi Party[edit]

Faulhaber helped persuade Gustav von Kahr not to support Hitler during the Beer Hall Putsch.[14] Its supporters turned against Faulhaber, who had denounced the Nazis in letters to Gustav Stresemann and Bavaria's Heinrich Held and blamed him for its failure; protests followed against Faulhaber, as well as the Pope, for an entire weekend.[15][16]: 169

In 1923 Faulhaber declared in a sermon that every human life was precious, including that of a Jew.[17] When the Nuncio wrote to Rome in 1923 complaining about the persecution of Catholics, he commented that "The attacks were especially focused on this learned and zealous" Faulhaber, who in his sermon and correspondence "had denounced the persecutions against the Jews."[18][16]: 169

In February 1924, Faulhaber spoke of Hitler and his movement to a meeting of Catholic students and academicians in Munich.[19] He spoke of the "originally pure spring" that had been "poisoned by later tributaries and by Kulturkampf." But Hitler, he asserted, knew better than his minions, and that the resurrection of Germany would require the help of Christianity.[19]

During the run up to the elections of March 1933, Faulhaber, unlike several other bishops who endorsed the Centre party, refrained from any comment in his pastoral letter issued on 10 February. The book of a Catholic author issued later in the year attributed the losses incurred by the Bavarian People's Party to the neutral position adopted by Faulhaber by asking "Had the Cardinal not indirectly pointed out the path to be followed in the future?"[20]

On 1 April 1933, the government supported a nationwide boycott of all Jewish stores and businesses. German bishops discussed possible responses against these measures but Faulhaber was of the opinion it would only make matters worse.[21] In the days preceding the boycott Cardinal Bertram asked for the opinion of brother bishops on whether the Church should protest. Faulhaber telegrammed Bertram that any such protest would be hopeless. And after the 1 April 1933 boycott of Jewish-owned-and-operated stores Cardinal Pacelli received a letter from Faulhaber explaining why the Church would not intervene to protect Jews: "This is not possible at this time because the struggle against the Jews would at the same time become a struggle against Catholics and because the Jews can help themselves as the sudden end of the boycott shows."[22] To Father Alois Wurm who asked why the Church did not condemn racist persecution in straightforward terms Faulhaber responded that the German episcopacy was "concerned with questions about Catholic schools, organizations, and sterilization which are more important for the Church in Germany than the Jews; the Jews can help themselves, why should the Jews expect help from the Church?"[23] According to Saul Friedländer, "The 1933 boycott of Jewish businesses was the first major test on a national scale of the attitude of the Christian churches toward the situation of the Jews under the new government. In historian Klaus Scholder's words, during the decisive days around the first of April, no bishop, no church dignitaries, no synod made any open declaration against the persecution of the Jews in Germany."[24]

Views on Communism[edit]

Cardinal Faulhaber had preached against communism in 1919, 1930 and from 1935 until about late 1941, but was silent on the topic from late 1942 until 1945; after the end of the war, he continued his public attacks against Bolshevism; the ideology which ruled over the Soviet Union and which Stalin was attempting to spread to all of Europe through the Communist International.[8]

Styles of

Michael von Faulhaber

Legacy[edit]

Different groups of people argue over Faulhaber's legacy. At the time, the Nazis reportedly considered Faulhaber a "friend of the Jews" and a Catholic "reactionary" (the term used by the Nazis to refer to individuals, especially traditionalist Christians, who did not accept the innovation of the scientific racism of Nazi antisemitism, criticised supposed pagan elements in the ideology, but were not left-wing).[92] Ronald Rychlak is of the opinion that the views expressed by people such as Faulhaber to Cardinal Pacelli (counselling silence on the assumption that speaking out would make matters worse) influenced Cardinal Pacelli's future responses to issues.[93]

The topic has been raised in post-war sociopolitics between Catholics and Jews. In "We Remember: A Reflection of the Shoah", a declaration issued by the Vatican in 1998 under Pope John Paul II's Papacy, Faulhaber's Advent sermons of 1933 were praised for their rejection of "Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda".[94] The principal author of the document was Cardinal Edward Cassidy, an Australian. At a meeting in 1999, a Jewish Rabbi, who as a sixteen-year-old lived in Munich at the time of the Advent sermons, recalled that Faulhaber had upheld the normative position of the Catholic Church "that with the coming of Christ, Jews and Judaism have lost their place in the world."[94] The Rabbi and some American historians at the meeting said that Faulhaber himself said he had only been defending the "Old Testament" and pre-Christian Jews, thus rejecting the race-based nature of Nazi antisemitism, not endorsing Rabbinic Judaism as valid. James Carroll, an American who authored the pro-Jewish work Constantine's Sword, reported that Cardinal Cassidy seemed embarrassed and replied that the disputed assertion in "We Remember" had not been in his original document but had been added "by historians".[94]