Misnagdim

Misnagdim (מתנגדים, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: Mitnagdim; singular misnaged/mitnaged) was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries.[1][2][3] The Misnagdim were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where Vilnius served as the bastion of the movement, but anti-Hasidic activity was undertaken by the establishment in many locales. The most severe clashes between the factions took place in the latter third of the 18th century; the failure to contain Hasidism led the Misnagdim to develop distinct religious philosophies and communal institutions, which were not merely a perpetuation of the old status quo but often innovative. The most notable results of these efforts, pioneered by Chaim of Volozhin and continued by his disciples, were the modern, independent yeshiva and the Musar movement. Since the late 19th century, tensions with the Hasidim largely subsided, and the heirs of Misnagdim adopted the epithet Litvishe or Litvaks.

This article is about the historical Rabbinic opposition to Hasidism from the 18th century, centred in Lithuania. For the non-Hasidic stream of Eastern European Judaism as well as the ethnic group of Lithuanian Jews, see Lithuanian Jews.Hasidism's changes and challenges[edit]

Most of the changes made by the Hasidim were the product of the Hasidic approach to Kabbalah, mainly as expressed by Isaac Luria (1534–1572) and his disciples, particularly Hayyim ben Joseph Vital (1543–1620). Luria greatly influenced both misnagdim and Hasidim, but the legalistic Misnagdim feared what they perceived as disturbing parallels in Hasidism to the heretical Sabbateans. An example of such an idea was that God entirely nullifies the universe. Depending on how this idea was preached and interpreted, it could give rise to pantheism, universally acknowledged as heresy, or lead to immoral behavior, since elements of Kabbalah can be misconstrued to de-emphasize ritual and glorify sexual metaphors as a more profound means of grasping some inner hidden notions in the Torah based on the Jews' intimate relationship with God. If God is present in everything, and if divinity is to be grasped in erotic terms, then—Misnagdim feared—Hasidim might feel justified in neglecting legal distinctions between the holy and the profane, and in engaging in inappropriate sexual activities.

The Misnagdim were seen as using yeshivas and scholarship as the center of learning while Hasidim had learning centered around the rebbe tied in with what they considered emotional displays of piety.[4]

The stress of Jewish prayer over Torah study and the Hasidic reinterpretation of Torah l'shma (Torah study for its own sake), was seen as a rejection of traditional Judaism.

Hasidim did not follow the traditional Ashkenazi prayer rite and instead used a combination of Ashkenazi and Sephardi rites based upon Lurianic Kabbalistic concepts.. This was seen as a rejection of the traditional liturgy and, due to the resulting need for separate synagogues, a breach of communal unity. In addition, they faced criticism for neglecting the halakhic times for prayer.[8]

Hasidic Jews also added some halakhic stringencies on kashrut (the laws of keeping kosher). They made certain changes in how livestock were slaughtered and in who was considered a reliable mashgiach (supervisor of kashrut). The result was that they essentially considered some kosher food as less kosher. This was seen as a change of traditional Judaism, and an over stringency of halakha, and, again, a breach of communal unity.

Response to the rise of Hasidism[edit]

With the rise of what would become known as Hasidism in the late 18th century, established conservative rabbinic authorities actively worked to stem its growth. Whereas before the breakaway Hasidic synagogues were occasionally opposed but largely checked, its spread into Lithuania and Belarus prompted a concerted effort by opposing rabbis to halt its spread.[7]

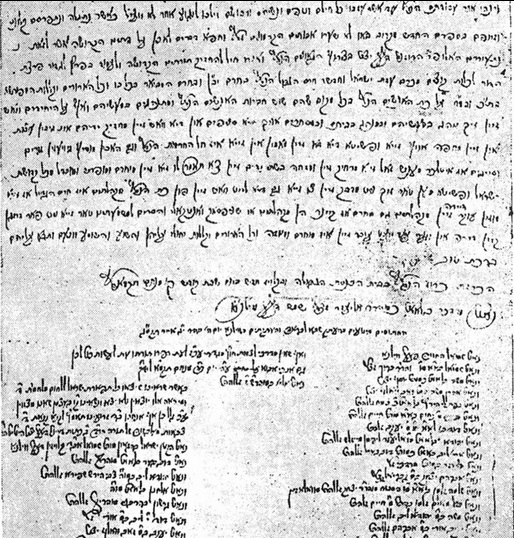

In late 1772, after uniting the scholars of Brisk, Minsk and other Belarusian and Lithuanian communities, the Vilna Gaon then issued the first of many polemical letters against the nascent Hasidic movement, which was included in the anti-Hasidic anthology, Zemir aritsim ve-ḥarvot tsurim (1772). The letters published in the anthology included pronouncements of excommunication against Hasidic leaders on the basis of their worship and habits, all of which were seen as unorthodox by the Misnagdim. This included but was not limited to unsanctioned places of worship and ecstatic prayers, as well as charges of smoking, dancing, and the drinking of alcohol. In total, this was seen to be a radical departure from the Misnagdic norm of asceticism, scholarship, and stoic demeanor in worship and general conduct, and was viewed as a development that needed to be suppressed.[7]

Between 1772 and 1791, other Misnagdic tracts of this type would follow, all targeting the Hasidim in an effort to contain and eradicate them from Jewish communities. The harshest of these denouncements came between 1785 and 1815 combined with petitioning of the Russian government to outlaw the Hasidim on the grounds of their being spies, traitors, and subversives.[7]

However, this would not be realized. After the death of the Vilna Gaon in 1797 and the partitions of Poland in 1793 and 1795, the regions of Poland where there were disputes between Misnagdim and Hasidim came under the control of governments that did not want to take sides in intra-Jewish conflicts, but that wanted instead to abolish Jewish autonomy. In 1804 Hasidism was legalized by the Imperial Russian government, and efforts by the Misnagdim to contain the now-widespread Hasidim were stymied.[7]

Winding down the battles[edit]

By the mid-19th century most of non-Hasidic Judaism had discontinued its struggle with Hasidism and had reconciled itself to the establishment of the latter as a fact. One reason for the reconciliation between the Hasidim and the Misnagdim was the rise of the Haskalah movement. While many followers of this movement were observant, it was also used by the absolutist state to change Jewish education and culture, which both Misnagdim and Hasidim perceived as a greater threat to religion than they represented to each other.[11][12] In the modern era, Misnagdim continue to thrive, but they are more commonly called "Litvishe" or "Yeshivish."