Nivelle offensive

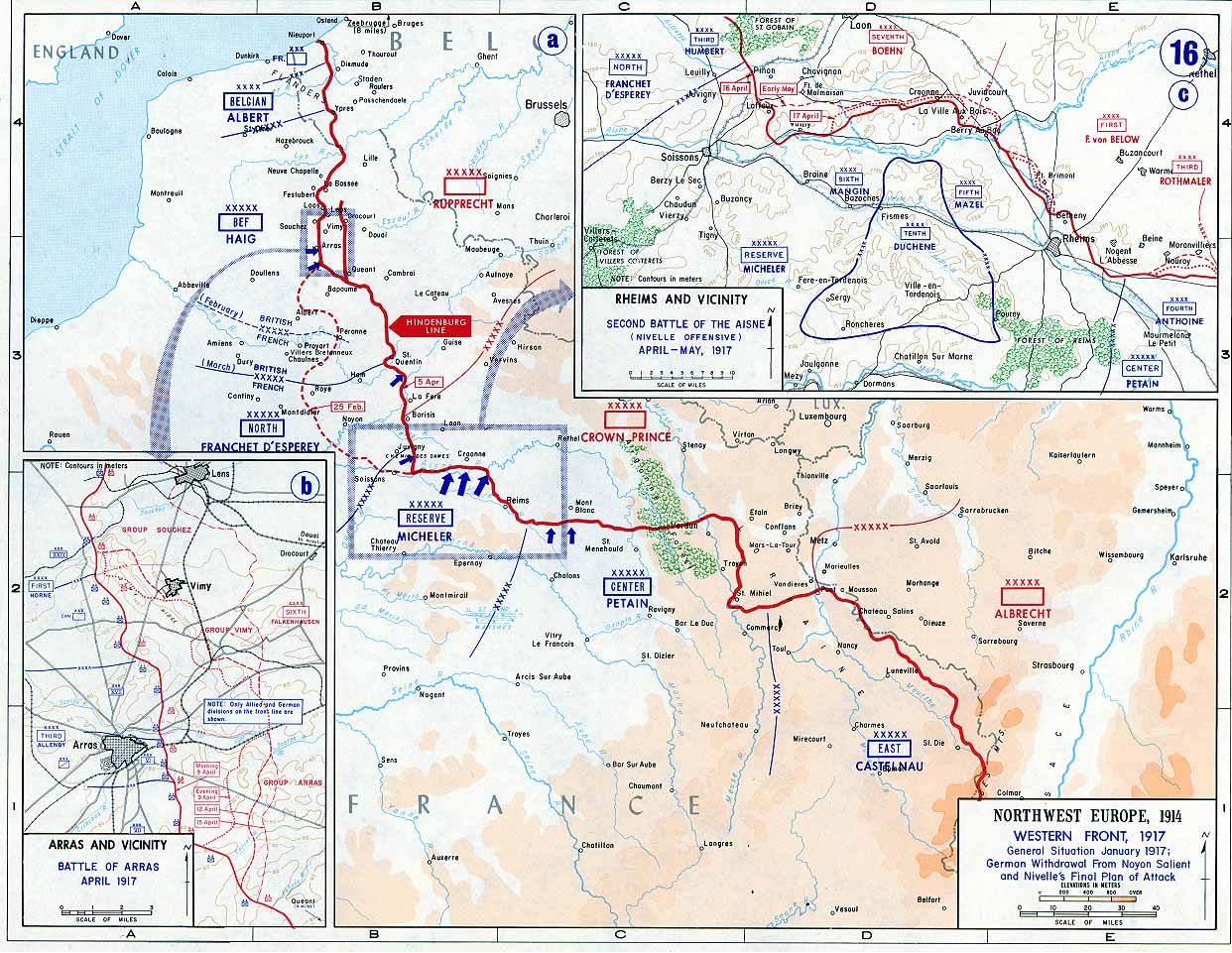

The Nivelle offensive (16 April – 9 May 1917) was a Franco-British operation on the Western Front in the First World War which was named after General Robert Nivelle, the commander-in-chief of the French metropolitan armies, who led the offensive. The French part of the offensive was intended to be strategically decisive by breaking through the German defences on the Aisne front within 48 hours, with casualties expected to be around 10,000 men. A preliminary attack was to be made by the French Third Army at St Quentin and the British First, Third and Fifth armies at Arras, to capture high ground and divert German reserves from the French fronts on the Aisne and in Champagne. The main offensive was to be delivered by the French on the Chemin des Dames ridge (the Second Battle of the Aisne).[a] A subsidiary attack was to be made by the Fourth Army (the Third Battle of Champagne).[b] The final stage of the offensive was to follow the meeting of the British and French armies, having broken through the German lines, to pursue the defeated German armies towards the German frontier.

The Franco-British attacks were tactically successful; the French Third Army of Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN, Northern Army Group) captured the German defences west of the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung) near St Quentin from 1 to 4 April, before further attacks were repulsed. The British Third and First armies achieved the deepest advance since trench warfare began, along the Scarpe river in the Battle of Arras, which inflicted many casualties on the Germans, attracted reserves and captured Vimy Ridge to the north. The main French offensive on the Aisne began on 16 April and also achieved considerable tactical success but the attempt to force a strategically decisive battle on the Germans was a costly failure and by 25 April the main offensive had been suspended.

The failure of the Nivelle strategy and the high number of French casualties led to mutinies, the dismissal of Nivelle, his replacement by Philippe Pétain and the adoption of a defensive strategy by the French, while their armies recuperated and rearmed. Fighting known as the Battle of the Observatories continued for local advantage all summer on the Chemin des Dames and along the Moronvilliers heights east of Reims. In late October, the French conducted the Battle of La Malmaison (23–27 October), a limited-objective attack on the west end of the Chemin-des-Dames, which forced the Germans to abandon their remaining positions on the ridge and retire across the Ailette valley. The British remained on the offensive for the rest of the year fighting the battles of Messines, 3rd Ypres and Cambrai.

Prelude[edit]

Franco-British preparations[edit]

Nivelle left Petain in command of Groupe d'armées de Centre (GAC) and established a new Groupe d'armées de Reserve (GAR, Joseph Micheler) for the attack along the Chemin des Dames with the Fifth Army (General Olivier Mazel), the Sixth Army (General Charles Mangin) and the Tenth Army (General Denis Duchêne). Forty-nine infantry and five cavalry divisions were massed on the Aisne front with 5,300 guns.[5] The ground at Brimont began to rise to the west towards Craonne and then reached a height of 180 m (590 ft) along a plateau which continued westwards to Fort Malmaison. The French held a bridgehead 20 km (12 mi) wide on the north bank of the Aisne, south of the Chemin des Dames, from Berry-au-Bac to Fort Condé on the road to Soissons.[6]

German preparations[edit]

German air reconnaissance was possible close to the front although longer-range sorties were impossible to protect because of the greater number of Allied aircraft. The qualitative superiority of German fighters enabled German air observers on short-range sorties, to detect British preparations for an attack on both sides of the Scarpe; accommodation for 150,000 men was identified in reconnaissance photographs. On 6 April a division was seen encamped near Arras, troop and transport columns crowded the streets, more narrow-gauge railways and artillery were seen to have moved closer to the front. British aerial activity opposite the 6th Army greatly increased and by 6 April Ludendorff was certain that an attack was imminent. By early April German air reinforcements had arrived the Arras front, telephone networks had been completed and a common communications system for the air and ground forces built.[7]

On the Aisne front German intelligence had warned that an attack on 15 April against German airfields and observation balloons by the Aéronautique Militaire was planned. The Luftstreitkräfte arranged to meet the attack but it was cancelled. Dawn reconnaissance had been ordered, to scrutinise French preparations and they gave the first warning of attack on 16 April. German artillery-observation aircraft crews were able to range guns on terrain features, areas and targets before the offensive began so that the positions of the heaviest French guns, advanced batteries and areas not under French bombardment could be reported quickly along with the accuracy of German return-fire. Ground communication with the German artillery was made more reliable by running telephone lines along steep slopes and deep valleys which were relatively free of French artillery-fire; wireless control stations had been set up during the winter to link aircraft to the guns.[8]

Morale[edit]

Verdun cost the French nearly 400,000 casualties and the conditions undermined morale, leading to a number of incidents of indiscipline. Although relatively minor, they reflected a belief among the rank and file that their sacrifices were not appreciated by their government or senior officers.[9] Combatants on both sides claimed the battle was the most psychologically exhausting of the war; recognising this, Pétain frequently rotated divisions, in a process known as the noria system. While this ensured units were withdrawn before their ability to fight was significantly eroded, it meant that a high proportion of the French army was affected by the battle.[10] By the beginning of 1917, morale was questionable, even in divisions with good combat records.[11]