Noh

Noh (能, Nō, derived from the Sino-Japanese word for "skill" or "talent") is a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Developed by Kan'ami and his son Zeami, it is the oldest major theater art that is still regularly performed today.[1] Although the terms Noh and nōgaku are sometimes used interchangeably, nōgaku encompasses both Noh and kyōgen. Traditionally, a full nōgaku program included several Noh plays with comedic kyōgen plays in between; an abbreviated program of two Noh plays with one kyōgen piece has become common today. Optionally, the ritual performance Okina may be presented in the very beginning of nōgaku presentation.

This article is about the classical Japanese dance theatre. For other uses, see Noh (disambiguation).Nōgaku Theater

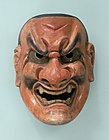

Noh is often based on tales from traditional literature with a supernatural being transformed into human form as a hero narrating a story. Noh integrates masks, costumes and various props in a dance-based performance, requiring highly trained actors and musicians. Emotions are primarily conveyed by stylized conventional gestures while the iconic masks represent the roles such as ghosts, women, deities, and demons. Written in late middle Japanese, the text "vividly describes the ordinary people of the twelfth to sixteenth centuries".[2] Having a strong emphasis on tradition rather than innovation, Noh is extremely codified and regulated by the iemoto system.

Zeami and Zenchiku describe a number of distinct qualities that are thought to be essential to the proper understanding of Noh as an art form.

Existing Noh theatres[edit]

Noh is still regularly performed today in public theatres as well as private theatres mostly located in major cities. There are more than 70 Noh theatres throughout Japan, presenting both professional and amateur productions.[53]

Public theatres include National Noh Theatre (Tokyo), Nagoya Noh Theater, Osaka Noh Theater, and Fukuoka Noh Theater. Each Noh school has its own permanent theatre, such as Kanze Noh Theater (Tokyo), Hosho Noh Theater (Tokyo), Kongo Noh Theater (Kyoto), Nara Komparu Noh Theater (Nara), and Taka no Kai (Fukuoka). Additionally, there are various prefectural and municipal theatres located throughout Japan that present touring professional companies and local amateur companies. In some regions, unique regional Noh such as Ogisai Kurokawa Noh have developed to form schools independent from five traditional schools.[16]

Audience etiquette[edit]

Audience etiquette is generally similar to formal western theatre—the audience quietly watches. Surtitles are not used, but some audience members follow along in the libretto. Because there are no curtains on the stage, the performance begins with the actors entering the stage and ends with their leaving the stage. The house lights are usually kept on during the performances, creating an intimate feel that provides a shared experience between the performers and the audience.[10]

At the end of the play, the actors file out slowly (most important first, with gaps between actors), and while they are on the bridge (hashigakari), the audience claps restrainedly. Between actors, clapping ceases, then begins again as the next actor leaves. Unlike in western theatre, there is no bowing, nor do the actors return to the stage after having left. A play may end with the shite character leaving the stage as part of the story (as in Kokaji, for instance)—rather than ending with all characters on stage—in which case one claps as the character exits.[18]

During the interval, tea, coffee, and wagashi (Japanese sweets) may be served in the lobby. In the Edo period, when Noh was a day-long affair, more substantial makunouchi' bentō (幕の内弁当, "between-acts lunchbox") were served. On special occasions, when the performance is over, お神酒 (o-miki, ceremonial sake) may be served in the lobby on the way out, as it happens in Shinto rituals.

The audience is seated in front of the stage, to the left side of the stage, and in the corner front-left of stage; these are in order of decreasing desirability. While the metsuke-bashira pillar obstructs the view of the stage, the actors are primarily at the corners, not the center, and thus the two aisles are located where the views of the two main actors would be obscured, ensuring a generally clear view regardless of seating.[10]